10 Most Underrated New Hollywood Movies, Ranked

The definition of “New Hollywood” is fast and loose. Following the advent of television, “Old” Hollywood’s studio system saw a decline in audience interest and attendance. Studios doubled down with a string of big-budget movies, trying to capture the magic of previous eras’ success, but unsurprisingly, they flopped. Studios, desperate to win back audiences, took a chance on scripts, actors, and directors that wouldn’t have been considered a decade earlier. Bonnie and Clyde is considered the landmark New Hollywood movie because it checks all the boxes: the critical old guard found it obnoxious, violent, and bleak, it didn’t follow action or tie up every loose end, it meandered, its editing didn’t conform to classic standards, and yet it was one of the highest-grossing films of 1967.

For this list, New Hollywood will be defined as films still made within the studio system, or whose directors utilized elements of that system. Otherwise, they’re just independent films, which had been going strong along a smaller distribution track, like the drive-in theater circuit, since the 1940s. So what’s an underrated New Hollywood movie? A film that managed to rub critics and audiences the wrong way, defying the new set of downbeat, gritty expectations. Movies that were just a little too ahead of their time, or came out too early to be appreciated in the New Hollywood framework; these are the underrated New Hollywood movies.

10

‘Frogs’ (1972)

This one’s a bit of a cheat, as it’s not exactly a Hollywood production, but who can resist an anti-patriarchal eco-horror, especially when it stars the rare un-mustached Sam Elliot? He plays wildlife photographer Pickett Smith, who gets clipped by the wealthy Crockett kids’ speedboat and ends up staying at the family manse for the 4th of July birthday party of family patriarch Jason (Ray Milland). Pickett tries warning the family that pollution spilling into the swamp is affecting the animals, and they should leave, but instead, family members and guests get picked off by various vicious critters.

Frogs has the difficult task of making adorably grumpy bullfrogs look menacing, at which it fails. But it succeeds at building up tension and atmosphere, which, considering someone is offed in an extremely goofy way by a different animal every few minutes, is no small feat. There’s little subtlety about a stubborn old man trashing the earth and refusing to change, and yet Frogs still feels like it takes its core message about the dangers of pollution seriously.

9

‘Electra Glide In Blue’ (1973)

The manager and producer of musical group Chicago takes a pay cut of $1 to hire New Hollywood’s premiere cinematographer to make a movie about a cop realizing he doesn’t like other cops, but loves being a cop. That is a 1970s movie sentence. Director James Guercio ended up arguing with cinematographer Conrad Hall (the man who lensed Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, Cool Hand Luke, Fat City, and many others) about the film’s look, and split the difference by letting Hall shoot interiors, while he shot exteriors.

Robert Blake plays Officer Wintergreen, on road patrol, but dreaming of working in homicide. He’s smart enough to get there, only to find petty office politics and other officers drag him back down. Blake was nominated for a Golden Globe, and the film was decently received. Electra Glide In Blue‘s focus on indignities large and small, among many other unusual choices (like its eternal final shot), marks it as an outsider film let inside.

8

‘Scarecrow’ (1973)

Gene Hackman and Al Pacino star as ex-con Max and former sailor Lion in this oddball buddy comedy. Actually, buddy comedy is too upbeat; it’s that recurring theme of New Hollywood, the Doomed Male Friendship. Scarecrow is less about plot and more about the relationship between Max and Lion as they travel across the country, partly for Lion to try and see the wife and new son he’d abandoned, and supposedly so that the two can open a car wash together. The title comes from Lion’s advice to quick-tempered Max to be like a scarecrow — scarecrows don’t actually scare the birds, they make them laugh, and you can’t fight if you’re laughing.

Scarecrow is a film that exists because Warner Bros. deliberately sought something smaller. Though very well received by critics at the time, and stars two actors fresh off giant hits (Hackman in The Conversation, Pacino in The Godfather), it just doesn’t get talked about much. It’s as inexplicable, or maybe as obvious, as the fact that the film was a box-office bomb. Unlike other Doomed Male Friendships like Midnight Cowboy, the two men aren’t united against any particular enemy or issue. They’re just united, adrift except for each other in the wide, worn-down country.

7

‘The Strange One’ (1957)

A strange one indeed, in that this film comes far earlier than the rest, and its cast and tech crew weren’t Hollywood guild members, but all part of New York’s Actors’ Studio. Producer Sam Spiegel, though an independent, was Hollywood royalty. He won the Best Picture Academy Award three times for Hollywood mega-hits On The Waterfront, Bridge on the River Kwai, and Lawrence of Arabia. And while it’s far earlier than New Hollywood proper, The Strange One has the same trademark outsider elements.

The film is best known for sneaking an overtly gay character past censors, but that glides by the rest of the movie’s over-the-top homoeroticism. In his debut role, Ben Gazzara plays sadistic senior Jocko De Paris (yes, really) at a southern military academy, terrorizing and bullying the younger cadets. After Jocko gets the son of a teacher expelled and forces all witnesses to lie and cover for him, a younger cadet decides to end Jocko’s reign of terror. The Strange One is partly a parable about how there’s not just one bad apple, but an entire system to allow them to flourish, and partly a character study as a thriller.

6

‘Popeye’ (1980)

Director Robert Altman was a darling of New Hollywood, with hit after hit featuring improvising ensemble casts, anti-war satire, and cross-cutting storylines. M*A*S*H, McCabe & Mrs. Miller, The Long Goodbye, Nashville, whatever the genre, Altman could bring it to the ’70s with music and sensibility. And then there’s Popeye. The live-action musical, which producer Robert Evans insisted be based on the comic strips, not the cartoons, hit nearly every production problem possible. And that’s not to bury the lede, it was the most drug-saturated set of all time.

But the film has wonderful leads, with Robin Williams as Popeye and Shelly Duvall as Olive Oyl. Popeye is messy, uneven, and ridiculous, but it’s also a musical based on a 1930s comic strip that carries over the manic energy and cartoonish fun. Popeye isn’t the greatest Altman film by a long shot, but it’s far better than its reputation makes it out to be. Unfortunately for Altman, Popeye‘s reputation led to trouble getting funding for projects for some time, so this film feels like the end capper of New Hollywood’s ascendency.

5

‘Let’s Scare Jessica To Death’ (1971)

Made and produced independently, Let’s Scare Jessica to Death was picked up by Paramount. The studio gave the film wide distribution and full publicity treatment that didn’t fit the film’s hippie gothic aesthetic. Jessica, recently released from a mental hospital, goes upstate with her husband Duncan and their friend Woody to an old farm Duncan purchased. They find a strange squatter, Emily, already living there, and instead of kicking her out, Jessica invites her to stay. As strange events happen around her, Jessica fears telling anyone, worried they’ll think she’s relapsed.

Let’s Scare Jessica to Death is The Fleetwood Mac Story from Christine McVie’s point of view, but it’s a haunting elegy to the end of the free love era as much as it is an unusual and unnerving ghost story. Though there’s plenty of direct scares, the film is more of a mood piece, with Jessica’s subjective paranoia playing against the film’s created reality. Hollywood taking a gamble on outsider John Hancock paid off, as he went on to direct studio films like Bang The Drum Slowly.

4

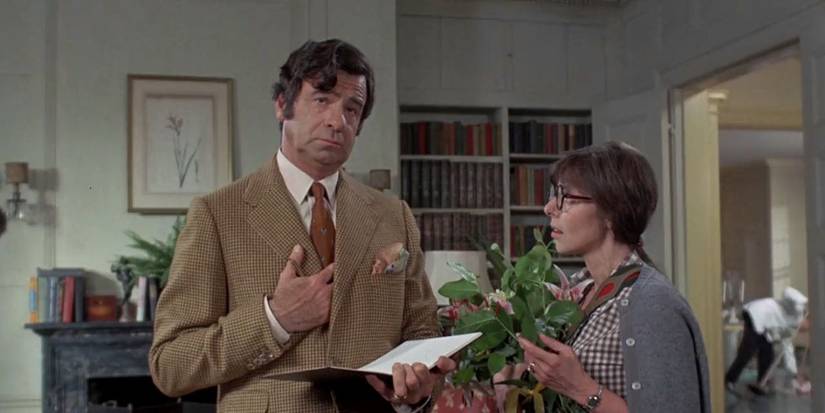

‘A New Leaf’ (1971)

Elaine May gets a bum rap in Hollywood for going wildly over budget and being a control freak (in that she rightly didn’t trust studios butting in on her work), but the results speak for themselves. A New Leaf is the most charming, winsome film about a broke layabout trying to murder his fiancée. Walter Matthau plays Henry, a newly broke scion. He contrives to marry clumsy botanist Henrietta (played by May herself) and off her, inheriting her vast fortune and continuing as he was. But Henrietta is so infuriatingly helpless, Henry inadvertently becomes more competent merely trying to enact his plan.

After she refused to show studio Paramount a rough cut of the reportedly 180-minute film, producer Robert Evans snatched A New Leaf away and cut out an entire movie’s worth of material, which is the version available. Its dark humor and idiosyncratic steps towards love still shine through. Though May tried suing Paramount to prevent the film’s release, A New Leaf remains a testament to her multiple talents. Who else could make marriage as a life sentence feel as sweet as it is punitive?

3

‘Seconds’ (1966)

Director John Frankenheimer had a string of hit Hollywood films under his belt, but Seconds flopped hard. A midlife crisis writ large, and a parable about the dangers of getting everything you want, the film follows successful but dissatisfied banker Arthur Hamilton. Offered a second chance by a shady company, Arthur pays the hefty fee, swaps identities, and gets the life he thought he wanted. After Arthur’s surgically altered to live his new bohemian life as Tony Wilson, he’s played by Rock Hudson.

Frankenheimer thought the film’s poor reception was due to failure to properly dramatize the second act, where Tony fails to adjust to his cool new life. Perhaps audiences didn’t like hearing that a sexy, youthful existence can be just as unhappy as a conservative, financially successful one. Whatever the failings, Seconds excels at projecting the subjective state onscreen. Frankenheimer and James Wong Howe, one of Hollywood’s greatest cinematographers, pushed the limits of the camera and lenses to create eerie, distorted images reflecting Arthur/Tony’s state of mind. Unsettling and cold, Arthur/Tony’s world feels claustrophobic and inescapable.

2

‘Zabriskie Point’ (1970)

To say it was widely derided undersells how hard Zabriskie Point was panned. Writing kindly about it, Rolling Stone‘s David Fricke says, “Zabriskie Point was one of the most extraordinary disasters in modern cinematic history.” It’s the kind of film that happens when studio money (here, MGM trying to lure youthful counterculture viewers) tries to buy artistic credibility, in the form of Italian director Michelangelo Antonioni, and the artist has too much freedom on uncertain terrain (this was Antonioni’s first, and only, American studio film).

It’s still Antonioni, though, so even if you find the simple hippie parable of a youthful meet-cute involving a stolen plane and cross-country work trip ludicrous, Zabriskie Point still looks gorgeous. Even the much-mocked dust orgy, where Open Theater actors writhe and wrestle around in a strange echo of leads Mark and Daria having sex, looks amazing. It’s clearly meant to be seen on the big screen, an intimate encounter turned into a grand, grotesque spectacle. There’s not much there, though. Zabriskie Point‘s infamous ending still hits hard; turn up the volume and tune out the poor reputation.

1

‘Head’ (1968)

Imagine taking your kid to see their favorite fake TV band’s movie, and within the first ten minutes, you see mermaids, psychedelia, and actual footage of a man shot dead. Welcome to Head, which starts hard and doesn’t let up. The Monkees’ sole movie came out after their TV show ended, so they had little to lose in going for broke, or so they thought. Head’s deconstruction of the Monkees, with a loose plot of them trying and failing to escape being characters in the movie itself, didn’t win over the alternative adults and alienated their fans, causing the Monkees’ record sales to drop.

It’s a shame, because Head is an absolute surrealist joy with gorgeous visuals like Davey Jones tap dancing to “Daddy’s Song,” cutting back and forth between positive and negative images achieved solely with costume and set. Carole King and Harry Nilsson contributed songs alongside Monkees Peter Tork and Michael Nesmith. There are cameos from Jack Nicholson, Annette Funicello, Frank Zappa, and more, and Golden Era Hollywood actor Victor Mature spoofs his screen presence, appearing literally larger than life as The Big Victor. Just like its opening minutes, what at first seems silly pop fluff quickly turns into an object lesson on media analysis and constructed personas, all the while remaining candy-colored silliness.