When I was twelve years old, I played Platoon with a younger kid from my neighborhood. That’s right: the brutal and tragic 1986 anti-war film directed by Oliver Stone, based on his own harrowing experiences in Vietnam—one summer afternoon, this grisly depiction of a disturbing and immortal war served as inspiration for my game of pretend. Clearly I missed the (not at all subtle) message. Or, rather, the message was irrelevant; what mattered was that it was believable. Platoon is gritty and dirty and utterly convincing—too gritty and dirty and convincing for a twelve-year-old, but alas. When we played the game—which constituted nothing more than running around a park with toy guns, diving into ditches, hiding behind trees, and communicating via nonsensical gesticulating—it wasn’t that the movie made me want to kill. It merely gave credibility to my imagination, grounding it in something that I now had reference for.

It’s still fucked up, though, the idea of a suburban white kid in a public park in Ohio cavorting around imitating characters who burn down Vietnamese villages. And whenever I tell people about it, the offensive incongruity is immediately apparent to all. But if I told them that the movie I was reenacting was Rambo: First Blood Part II or Missing in Action, no one would find the anecdote surprising or amusing in the same way, even though both are also Vietnam-related war films. I’m not trying to defend my Platoon game—it was fucked up—but there’s something curious in the way everyone has always responded to this childhood memory, the near universal understanding that a young boy mimicking Platoon is different and worse and less appropriate than that same kid pretending to be Rambo. It points toward our conflicted relationship to the power and purpose of movies. We somehow both over- and underestimate the impact cinematic art has on us. When it’s a serious-minded story with deep meaning, we extol its force as powerful, even life-changing, but when it’s a silly movie—over-the-top action, superhero, kids’ animation—that perhaps contains its own political or ethical content, we tend to under-value its influence, if not dismiss it altogether.

Depending on which auteur-driven, endlessly mythologized decade of American filmmaking one is extolling, the role that big-budget Hollywood films of the 1980s plays in the narrative is positional: they’re the death knell to personal filmmaking in stories about the ‘70s, but they become the rousing inspiration for the daring mavericks of the indie movement in the ‘90s. Of course, these decadal constructions are arbitrary: the New Hollywood of the ‘70s, Peter Biskind noted in Down and Dirty Pictures, “more or less” ended in 1975 with the release of Jaws, while many of the tentpoles of the ‘80s were born in the previous decade and continued into the subsequent one. But what we mean by ‘80s Hollywood is the same in either case: a “merger mania,” as Sharon Waxman puts it in Rebels on the Backlot, where by the end “every major studio had been successively gobbled up by huge multinational corporations that were focused brutally on the bottom line.” As James Mottram wrote in The Sundance Kids, it was “the era of the talent agency” that produced “disposable fare.” As such, the time of Reagan the actor-president, Yuppies, and corporate hegemony hasn’t received the same laudatory mythologizing as the New Hollywood before it or the indie boom after it. Indeed, the decade is primarily invoked to contrast its crass commercialism to the superior sensibilities of its numerical neighbors.

A book like Nick de Semlyen’s The Last Action Heroes: The Triumphs, Flops, and Feuds of Hollywood’s Kings of Carnage—which seeks to revel in the gloriously silly films of Arnold Schwarzenegger, Sylvester Stallone, Chuck Norris, Steven Seagal, Jackie Chan, et al—cannot, obviously, operate on the notion that the ‘80s represents the death of cinema, but de Semlyen also can’t straight-facedly argue that these films are “good” by any metric. Most of the movies made by this crew of stars are really terrible (a few terrible-good, most terrible-terrible), but only if your criteria include conventional expectations like complex characters or coherent plots or a healthy grasp on basic realities. These films don’t aspire to goodness, as we’ll see, so why bother, anyway?

Are we sure we understand the power of film? As I read through The Last Action Heroes, I kept thinking not about the over-the-top cinematic action from the 1980s, but about the over-the-top gun deaths of America over the past four decades. I don’t mean to suggest that mass murderers watched some piece of junk from Steven Seagal and it made them want to go on a killing spree, but whenever I see the macho bullshit surrounding the continued legality of guns—“I own guns to protect my family,” “good guys with guns,” etc.—I can’t help but feel as if these people are play-acting—or, I suppose, movie-acting. They aren’t consciously pretending, like children would, but rather tying themselves behaviorally to a paragon of their beliefs. Tapping into an image of cinematic heroism, the ease with which stock phrases and macho posturing emanate out of them is a reassuring reinforcement of their claims about the purposes of being armed. It is always justified as “protection,” a hero’s role, and never murder, a villain’s role. Protection assumes an aggressor, an unspoken and ill-defined (but not at all difficult to identify) figure lurking in the edges of the argument. Just who are we protecting ourselves from? In this scenario, the effect of movies isn’t easily measured in causal terms. It’s a complex process that infiltrates our psyches in all manner of ways—some harmless, some not.

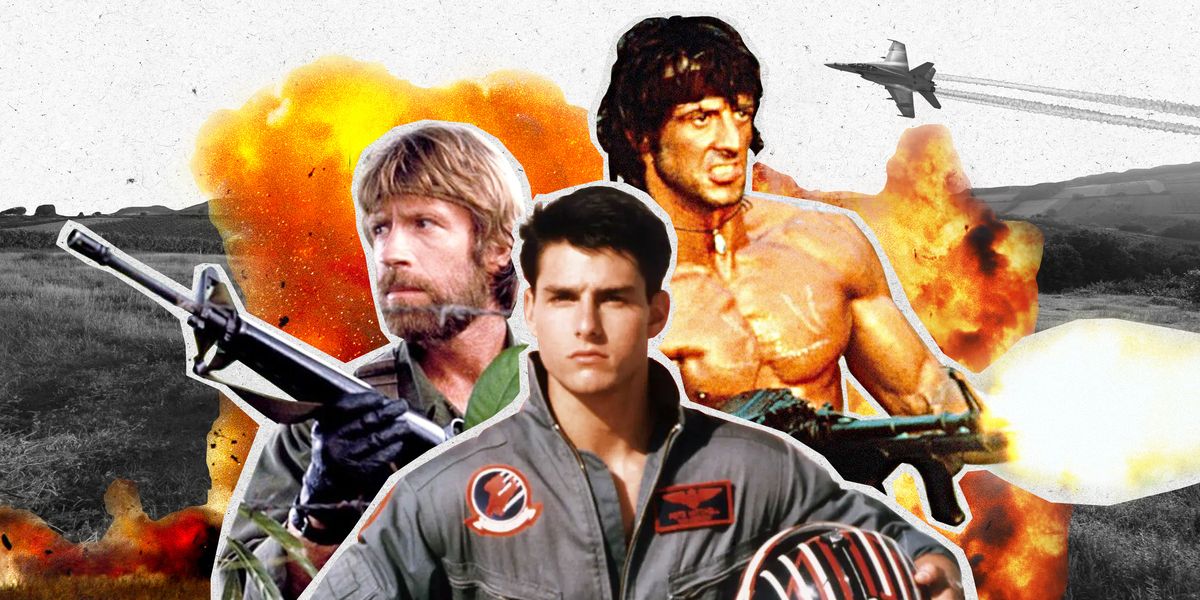

What we’ve been presented with over the past decades are images of extremely strong and physically intimidating men becoming morally-driven vigilantes, loaded with absurd weaponry, impossible skills, and moral sanctimony. It’s John Rambo charging into the base with an Uzi at the end of Rambo: First Blood Part II, lecturing the Major about rescuing the rest of the POWs. It’s John Matrix decimating the former South American dictator’s villa with a fucking rocker launcher in Commando. It’s Nico Toscani beating up an entire bar because none of them take his search for a young woman as seriously as he’d like. It’s James Braddock riding in a bulletproof raft bedazzled to look like a cartoon shark, with no covering or shield, standing up fully exposed at the helm of a turret, killing dozens and dozens of firing heavies whose bullets all magically miss their mark.

These scenes are not good filmmaking. They’re goofy and over the top, and Sly, Arnold, Chuck, and Seagal are all so intoxicated with their characters’ righteousness you can practically hear their erections. But for all that, they’re still much more effective than such silliness suggests. These set pieces appeal to a deep-seated part of us—the part that relishes in retaliation—and although each standalone film affects us only so much, the cumulative effect, over years and years and image after image, is something else entirely. Certainly anyone can see how a steady diet of venerated misanthropes who solve problems with violence has created a mythology for armed self-policing.

These concerns aren’t new. Throughout film’s history, critics have repeatedly worried about its outsized impact. Walter Benjamin, in the ‘30s, wrote that cinema “affords a spectacle unimaginable anywhere at any time before this.” Clement Greenberg, around the same time, worried that “kitsch” like Hollywood movies could be employed as propaganda by some fascist governmental apparatus. Serious film, for him, was incorruptible. But by the ‘80s, we’d learned to embrace the kitsch, the Camp, and the bad in film, as ironic appreciation for cult classics, midnight movies, and Ed Wood-level ineptitude grew with the advent of TV reruns, late-night screenings, and books like Harry and Michael Medved’s The Golden Turkey Awards. In his essay “Bad Movies” from 1980, J. Hoberman noted that “it is possible for a film to succeed because it failed.” Or as Susan Sontag put it in “Notes on ‘Camp’”: “It’s good because it’s awful.”

Film has always had two tracks as it developed as an art form—the burgeoning aesthetics and theories and techniques of Films, and the populist, unchallenging, crowd-pleasers called Movies. Critics didn’t take the latter as seriously as they might have, treating them as kitsch, as Camp, as Bad—to be appreciated ironically and with little consideration of its intended message, only its failure to make it. But the pre-’80s critical community ignored Movies at their own peril, as it was in the 1980s that the true power of cinematic storytelling hit its stride. I don’t mean in terms of quality (if that hasn’t been made apparent yet), but of effectiveness.

Technology, creative development, and millions and millions of dollars had all conspired to make even a mediocre movie extremely effective as a storytelling medium. That unimaginable spectacle that Benjamin described a half century earlier had grown into something bigger, ungainlier, and yet paradoxically easier to make than ever. Movies borrow strength from every other creative field—music, theater, photography, choreography, architecture, fashion, graphic design, et al—and combine it all to invent and present convincing images unlike anything experienced before in human history, at least not at this heightened a degree. Greenberg’s fear that a political apparatus would use Hollywood kitsch for propagandistic purposes proved right and wrong, because although the U.S. Navy was involved with Top Gun, using it as a supposedly very successful recruitment initiative (as the Army did with Rambo), Hollywood in the ‘80s showed that government intervention is mostly unnecessary. The filmmakers will do the work for them.

Nick de Semlyen is, of course, aware of the morally dubious nature of some of these films, but his objections are more perfunctory than critically generative. For example, when writing about Chuck Norris’s 1984 film Missing in Action, which tapped into the popular (and incorrect) right-wing theory that many US soldiers were still being held captive in Vietnam, despite the war’s end, de Semlyen notes that some people objected to this, quoting Oliver Stone as his counterpoint. Stone calls the “MIA movement” a “fetish of the American political right,” saying that the theory’s persistence was “played out for political reasons.” Stone is often dismissed as a political fantasist and conspiracy theorist himself, but for the left, with films like JFK taking numerous liberties with the truth. Quoting Stone here is a kind of slick bothsidesism.

But consider the impact of Missing in Action. James Bruner, the screenwriter, is quoted in The Last Action Heroes saying that the movie may not have stirred people “in New York and Los Angeles, but the rest of the country” ate it up. “It was a very emotional thing,” Bruner recalls. “When we went to see the picture, people were standing up and cheering at the end in the theater.” What happens when an art form with unparalleled power, wide reach, and the blind eye of critics disseminates false ideas that were “tapping into the sense of injustice held by a large swath of America,” as de Semlyen puts it? Well, don’t look to de Semlyen for the answer, as such a zoomed-out conundrum is beyond his book’s purview.

I’m not sure if such an explanation exists, as we may never know how much damage these films have wrought. The way a story like Missing in Action makes its argument is via emotional punch, not intellectual rigor. What Norris was getting at, to millions of Americans, felt right. “THE WAR’S NOT OVER UNTIL THE LAST MAN COMES HOME!” screamed the poster, which featured an absurd hero shot of Norris brandishing a ludicrously oversized weapon (many of the guns used in action movies are not practical, but as John McTiernan says of the arsenal in his film Predator, they “just looked cool”). For Norris and his ideologically aligned fans, the war never ended, which meant that a resolution was still required, one Norris and Stallone were happy to provide—only this time, as de Semlyen writes of Rambo: First Blood Part II, “military power was celebrated, not apologized for.” Is it really such a simple binary? Is contrition the opposite of celebration? Were those arguing against America’s involvement in Vietnam seeking an apology?

Guns, like movies, are much more effective than they once were. The disproportion between the deadly power of a gun and the motivation behind its use (often during emotionally intense episodes) is not unlike the gap between the moral complexity of violence and the (let’s be honest) less than thoughtful approach of militarily jingoistic cinema. Guns can make our most debased and fleeting thoughts of anger manifest—they can kill as quickly as we can think—and movies give our many reductive ideas about the world an incredibly effective outlet, one whose influence far outweighs the credibility of the arguments.

Watching many of these movies now, I’m reminded of an insight that Richard Schickel had about Ronald Reagan. In his lengthy review of Garry Wills’s 1987 book Reagan’s America: Innocents at Home for Film Comment, Schickel relates an incident from 1983 in which Reagan, while hosting the prime minister of Israel, “implies, or seems to imply, or something, that he was part of a Signal Corps unit filming the Nazi death camps as they are liberated.” Even more appalling, Reagan claimed that, while filming, “there was one particularly moving piece of footage that he felt he ought to sequester because he thought someday people would question the authenticity of the Holocaust and…one day someone did exactly that in his presence and he had this footage.” Reagan confabulated notoriously—the great fabricator—and Schickel notes how people wouldn’t get all that upset about such lies from America’s 40th president:

For we recognize in Reagan something we indulge in ourselves and in our friends—namely, our not entirely conscious, not entirely unconscious desire to reshape the maddening ambiguities of reality as we commonly experience it into the narratively neat, psychologically gratifying form of an old-fashioned movie, with a beginning, a middle, an end, and, above all, a central figure we have no trouble rooting for—who is, of course, ourselves.

In the ‘80s, it was so normal to pretend life was a movie that we excused the president from doing it. In 1985, just before giving a speech addressing the resolution of an episode of the Lebanese hostage crisis, Reagan was caught on a live mic saying, “Boy, I’m glad I saw Rambo last night. Now I know what to do next time.” This president had starred in movies himself, which seemed to make his mendacious proclivity and heroic posturing more understandable. But why do we do it? Schickel asks: “Does this represent a basic human need in search of a form that the dreamy movies kindly provide? Or did the suddenly pervasive movies propose for us kinds of transformations we had never before known we wanted or needed to make?”

In that J. Hoberman essay, he mentions “the paradigmatic Camp icon Maria Montez,” whose acting was “so unconvincing” that her fictional movies came across rather as “unintended documentaries of a romantic, narcissistic young woman dressing up in pasty jewels, striking fantastic poses, queening it over an all-too-obviously make-believe world.” What The Last Action Heroes makes clear is that what we’re actually viewing are not fictional revisions of America’s wars or thrillers about lone wolves taking down the bad guys, but rather “unintended documentaries” of young, narcissistic men with enormous egos dressing up in tough-guy attire and kinging it out in an all-too-obviously make-believe world. It was as if these were movies about guys pretending to be in movies—the same impulse that drove me to reenact Platoon, but elevated to the grandest scale. Like Reagan’s self-mythologizing bullshit, these displays add a pathetic and tragic dimension to main character energy, because their playacting isn’t frivolous. Our lives are now menaced by isolated, gun-toting misanthropes who provide self-aggrandizing motivations for their actions, and who come from that “large swath of America” with a “sense of injustice.” These movies—and the cultures they tapped into—contributed to this state, which makes it hard to see them merely as badass fun.

“America in the 1970s was crying out for a hero,” de Semlyen writes in the introduction, but what America got only mimicked heroism, using it for dramatic expediency and galling self-indulgence. It seems appropriate to invoke a movie quote here, and the one I kept thinking about was from the 1995 film The American President, in which Michael J. Fox’s character says to Michael Douglas’s President Shepherd, “People want leadership, Mr. President, and in the absence of genuine leadership, they’ll listen to anyone who steps up to the microphone. They want leadership. They’re so thirsty for it they’ll crawl through the desert toward a mirage, and when they discover there’s no water, they’ll drink the sand.” That’s what these action “heroes” really are: sand.