By

Fred Blosser

“Tales

of Adventure Collection 2,” a special edition, Blu-ray box set from

Australia’s Imprint Films, gathers five movies from the 1940s and ‘50s with

“wild and dangerous” jungle settings. To

the best of my memory, I don’t recall seeing any of them among the scores of

jungle pictures I enjoyed as a kid in the ‘50s and early ‘60s, either on the

big screen or on local TV morning movie matinees. Of the five diverse selections in the Imprint

box set, three are Republic Pictures productions, the fourth is a Paramount

release, and the fifth bears the Columbia Pictures logo. All five feature superior transfers (the

three Republic entries are transfers from 4K scans of the original negatives)

and captions for the deaf and hard of hearing, and four of them come with

excellent audio commentaries. Younger

viewers be aware, the films tend to reflect attitudes about race and

conservation that were commonplace seventy years ago, but frowned upon today;

you won’t see anything remotely like Black Panther’s democratic technocracy of

Wakanda here.

The

older two Republic releases, both in black-and-white and paired here on one

disc, underscore the studio’s reputation as a purveyor of lowbrow entertainment

with stingy production values. “Angel on

the Amazon” (1948) begins with Christine Ridgeway (Vera Hruba Ralston) trekking

through the Amazon jungle with safari hat and rifle, stalking panthers. It promises (or threatens, if you’re a

conservationist) to become a film about big-game hunting, where wild animals

exist to be turned into trophy heads. But

then Christine’s station wagon breaks down, and she radios for help. Pilot Jim Warburton (George Brent) flies in

with the needed carburetor part, just in time for the party to escape from

“headhunters.” This may be the only

jungle movie in history where rescue depends on a delivery from Auto Zone. Jim is enchanted by Christine, but she has

something to hide and refuses to warm up to his advances. Later, meeting Jim again in Rio de Janeiro,

she becomes frightened when an elderly, apparently harmless man watches her

from a distance. As film historian

Philippa Berry notes on the informative audio commentary for the Blu-ray, the

answer to the mystery revolves around the then-popular theme of physical

effects from psychological trauma, here given a mystical and somewhat absurd

twist. The studio-bound sets and back

projection that waft the characters from the Amazon to Rio and then to

Pasadena, California, are charmingly phoney. George Brent and two other fading co-stars from the 1930s, the

aristocratic Brian Aherne and Constance Bennett, stoutly maintain straight

faces in the backlot rain forest.

“Daughter

of the Jungle” (1949) is even more formulaic, as a young blonde woman raised in

the jungle comes to the aid of pilot Paul Cooper (James Cardwell), a policeman,

and two gangsters in the lawman’s custody when their plane crashes somewhere in

Africa. Called Ticoora by the local

tribe, she is actually Irene Walker, who was stranded with her millionaire

father in their own plane crash twelve years before. As film historian Gary Gerani notes in his

audio commentary track, Ticoora is one of a long line of virginal jungle sirens

in movies that range from the ridiculously sublime, like 1959’s “Green

Mansions,” to the sublimely ridiculous, like 1983’s “Sheena, Queen of the

Jungle.” She can summon elephants with a

Tarzan-like yodel that recalls Carol Burnett’s parodies on her old TV

show. As Ticoora leads the party to

safety, the oily head gangster, Kraik, schemes a way to claim her inheritance,

which awaits in New York. Some viewers

will see Kraik, played by the great Sheldon Leonard with a constant volley of

“dese, dose, and dem” insults, as the only reason to stay with the movie’s plod

through lions, gorillas, crocodiles, and indigenous Africans played by white

actors in greasepaint. Others (I plead

guilty) tend to view unassuming, ramshackle pictures like this one more

leniently, providing we can accept if not endorse their racial attitudes as a

product of their times. Consistent with

Republic’s nickel-and-diming on its B-feature releases, especially those made

in the late ‘40s, the more spectacular long shots of Ticoora swinging from

vines in her above-the-knee jungle skirt were recycled from one of the studio’s

earlier releases. In those scenes, it’s

actually Francis Gifford’s stunt doubles in the same outfit from the 1941

serial “Jungle Girl,” not Lois Hall who plays Ticoora in the new footage. Gary Gerani’s audio commentary provides lots

of information about the cast, including the two obscure leads, Lois Hall and

James Cardwell. Gerani points out that

the Blu-ray print, from the original negative, presents the movie’s full

80-minute version for the first time ever. The 69-minute theatrical release in 1949 omitted some B-roll filler and

some scenes where Paul woos Irene. More

action, less kissy, was crucial for encouraging positive playground

word-of-mouth from sixth graders in the audience—the pint-sized forerunners of

today’s Tik-Tok influencers.

The

third movie retrieved from Republic’s vaults, “Fair Wind to Java” (1953), was

one of the studio’s intermittent efforts to offer more expensive productions in

living Trucolor, with a rousing Victor Young musical score, to compete with

major postwar costume epics from the MGM and Paramount powerhouses. Ironically, Paramount now owns the rights to

Republic’s home video library. In 1883

Indonesia, New England sea captain Boll (Fred MacMurray) picks up the trail of

lost diamonds also sought by a pirate chief, Pulo Besar (Robert Douglas). Obstacles include the pirates, some scurvy

knaves in Boll’s own crew, Dutch colonial authorities, and the fact that the

only person who can direct Boll to the treasure is dancing girl Kim Kim (Vera

Hruba Ralston), who has only an imperfect memory of the route from her

childhood. Substitute Indiana Jones for

Captain Boll, and you’d hardly notice the switch. It turns out that the gems are hidden in a

temple on Fire Island—unfortunately for the captain, not the friendly enclave

of Fire Island, N.Y., but the volcanic peak of Krakatoa. Will Krakatoa blow up just as the rival

treasure hunters make landfall there? Are you kidding? The script doesn’t disappoint, and neither do the FX by

Republic’s in-house technical team, Howard and Theodore Lydecker. A former ice skating star who escaped

Czechoslovakia ahead of the Nazis, Ralston was the wife of Republic studio head

Herbert J. Yates and widely derided as a beneficiary of nepotism who couldn’t

act her way out of an audition. She was

still a punch line for comics in the 1960s, long after most people had

forgotten the point of the joke. In

reality, both here and in “Angel on the Amazon,” she is an appealing performer,

no more deserving of ridicule than other actresses of her time with careers

mainly in escapist pictures. The sultry

but vulnerable Kim Kim was the kind of role that Hedy Lamarr might have played

under other circumstances. Ralston’s

performance is at least as engaging, and she looks mighty nice in brunette

makeup and sarong.

If

you first met Fred MacMurray as the star of “My Three Sons,” as I did as a kid,

it may take some adjustment to see him in action-hero mode. It’’s no big deal when Dwayne Johnson or

Jason Statham slings a bandolier over his shoulder or has his shirt torn off in

a brawl with a pugnacious sailor . . . but Fred MacMurray? When Boll ponders whether or not to trust his

shifty first mate Flint (John Russell), it’s a little like MacMurray’s suburban

dad asking Uncle Charlie if he should trust Robbie and Chip with the family

car. John Wayne was originally

envisioned for the role, following his starring credit in a similar Republic

production, “Wake of the Red Witch,” but MacMurray wasn’t completely out of his

element, having played lawmen and gunslingers in several Westerns before his

sitcom days. Frankly, it’s fun to see

the normally buttoned-down actor shooting it out with the pirates and racing a

tsunami. Imprint includes another

excellent commentary, this one by historian Samm Deighan. As she notes, colourfully mounted and briskly

scripted movies like this were designed to attract the whole family in those

days before Hollywood marketing fractured along lines of audience gender, age,

and race. As she observes, Junior might

not recognise the sado-sexual elements of the scene where Pulo Besar’s burly

torturer (played by Buddy Baer!) strips Kim Kim and plies his whip across her

bare back. All in a day’s work in the

dungeon. But dad likely would have sat

up and paid close attention.

Only

a year later (1954), Paramount’s “Elephant Walk” furthered Hollywood’s trend of

filming exteriors for its more prestigious movies in actual overseas locations

rather than relying on studio mockups, as “Fair Wind to Java” did. Ruth Wiley (Elizabeth Taylor at her most

luminous) travels to Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) with her new husband John (Peter

Finch), the charming and prosperous owner of a tea plantation. Initially, Ruth is enraptured by the lush

countryside and John’s bungalow, Elephant Walk, actually a mansion almost as

large as Grand Central Station and a lot more lavish. But trouble portends as Ruth realizes that

the memory of John’s imperious father Tom, reverently called “the Governor” by

John and the other British residents, still pervades and controls the

household. The elderly head steward,

Appuhamy (Abraham Sofaer), is quietly hostile when Ruth questions the need to

continue running the house exactly as it was run in the Governor’s day. In trying to communicate with the other

indigenous servants and workers, she runs into the barriers of language and

culture. The estate itself, complete

with Old Tom’s mausoleum in the backyard, is built across an ancestral path the

native elephants still try to use as a short cut to their watering holes. Hence its name. Wiley keeps the peripatetic pachyderms out

with a wall. His plantation manager

(Dana Andrews) is more sympathetic to Ruth, and the two fall in love as the

increasingly surly John lapses back into old habits of drinking all night with

rowdy fellow expatriates who camp out in the sprawling mansion. Andrews’ character is named “Dick Carver,”

the kind of name you’re not likely to see on credits anymore outside

Pornhub. I wonder if some moviegoers in

1954 found it funny too?

If

the combination of shaky marriage, illicit affair, and luxurious colonial life on a jungle plantation sounds

familiar, you may be thinking of “Out of Africa” (1985) or the less

romanticised “White Mischief” (1987), the latest examples of this particular

jungle sub-genre of domestic drama in the tropics. As Gary Gerani points out in his audio

commentary, enthusiasts of melodrama will also cry “Rebecca!” in the subplot

about the shadow that “the Governor’s” pernicious, posthumous influence casts

over the married couple. The movie’s

lush Technicolor palate, William Dieterle’s sleek direction, the special FX of

an elephant stampede, Edith Head’s ensembles for Liz, and Franz Waxman’s

symphonic score have an old-fashioned Hollywood polish, shown to good effect on

the Blu-ray. But as Gerani notes, the

script by John Lee Mahin, based on a 1948 novel, offers an implicit political

commentary too. As viewers of “The

Crown” know, British rule was already crumbling in the Third World in the early

1950s and would soon fall, just like Wylie’s wall faces a renewed assault by

drought-stricken elephants in the final half hour of the movie. Thanks to the capable cast, glossy production

values, and a script that takes interesting, unexpected turns, I liked

“Elephant Walk” more than I thought I would.

Terence

Young’s “Safari” (1956) from Columbia Pictures begins with a jaunty title song

to a percussive beat that wouldn’t be out of place in “The Lion King”—“We’re on

safari, beat that drum, / We’re on safari to kingdom come”—leading you to think

that the picture will be a romp like “Call Me Bwana” (1963), “Clarence the

Cross-Eyed Lion” (1965), or the last gasp of jungle comedies so far, “George of

the Jungle” (1997). But the story takes

a grim turn almost immediately. An

American guide and hunter in Kenya, Ken Duffield (Victor Mature), is called

back from a safari to find his 10-year-old son murdered and his home burned by

Mau Mau terrorists. He determines to

find and kill the murderer, Jeroge (Earl Cameron), a formerly trusted servant

who, unknown to Duffield, had “taken the Mau Mau oath.” The British authorities revoke Duffield’s

license to keep him from interfering with their attempts to apprehend Jeroge

and the other culprits, but then they hand it back under pressure from Sir

Vincent Brampton (Roland Culver), who comes to Africa to kill a notorious lion

called “Hatari.” “You know what ‘Hatari’

means, don’t you?” Duffield asks. “It

means danger”—the very tagline used for Howard Hawks’ movie of the same name a

few years later. Coincidence? Brampton is a wealthy, borderline sociopathic

bully who makes life miserable for his finance Linda (Janet Leigh) and

assistant Brian (John Justin), and Duffield doesn’t much care for him

either. But the millionaire insists on

hiring Duffield as the best in the business, and the hunter uses the safari as

a pretext for pursuing Jeroge into the bush. The script juxtaposes Duffield’s chase after Jeroge with Brampton’s

determination to bag Hatari, but the millionaire is such an unpleasant

character (well played by Culver) that most of us will hope the lion wins.

This

was one of the last “big bwana” movies where no one thinks twice about killing

wild animals for sport, and viewers sensitive about the subject may not share

Sir Vincent’s enthusiasm for Ken Duffield’s talents, or the production’s

matter-of-fact scenes of animals collapsing from gunshots. The political material about the Mau Maus is

a little dicey too; the Mau Mau insurrection of 1952-60 was more complicated

than the script suggests. Poster art for

the movie, reproduced on the Blu-ray sleeve, depicts a fearsomely painted

African. Actually, it isn’t a Mau Mau

but a friendly Massai tribesman; Linda makes the same mistake in the movie

before learning that the Massai have agreed to help Duffield track Jeroge. Squirm-worthy dialogue occurs as well, when

Duffield and Brampton alike refer to the hunter’s African bearers and camp

personnel as “boys.” But Terence Young’s

brisk, muscular direction on outdoor locations in Kenya is exemplary, and the

CinemaScope vistas of Kenya in Technicolor are sumptuous. This was one of Young’s four projects behind

the camera for Irving Allen and Albert R. Broccoli’s Warwick Films, preceding

Broccoli’s later partnership with Harry Saltzman when the producers engaged

Young to direct the inaugural James Bond entries. For 007 fans, it may be heresy to suggest

that his work on “Safari” equals that on his best Bond picture, “From Russia

With Love,” but so be it. The Imprint

Blu-ray doesn’t contain an audio commentary or other special features, but the

hi-def transfer at the 2.55:1 widescreen aspect ratio is perfect.

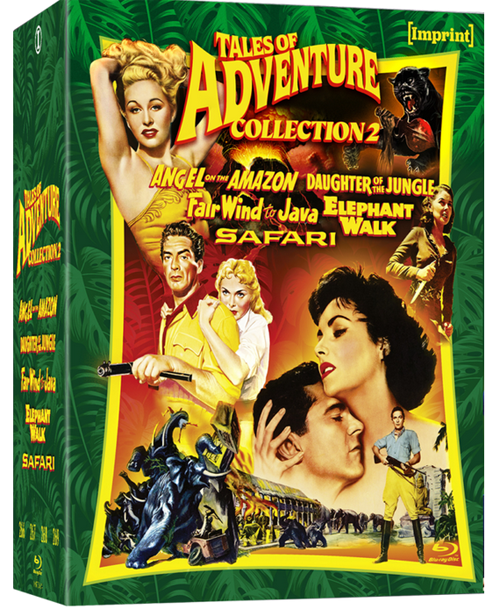

“Tales

of Adventure Collection 2” contains the four region-free Blu-ray Discs in a sturdy

hardbox, illustrated with a collage from the poster art for the five movies in

the set. Limited to a special edition of

1,500 copies, it can be ordered HERE. (Note: prices are in Australian dollars. Use currency converter for non-Australian orders.)