(ANALYSIS) Exorcism movies are making a comeback — and the reasons are more interesting than you might think.

And if you think there have been a lot of exorcism movies lately, you’re right.

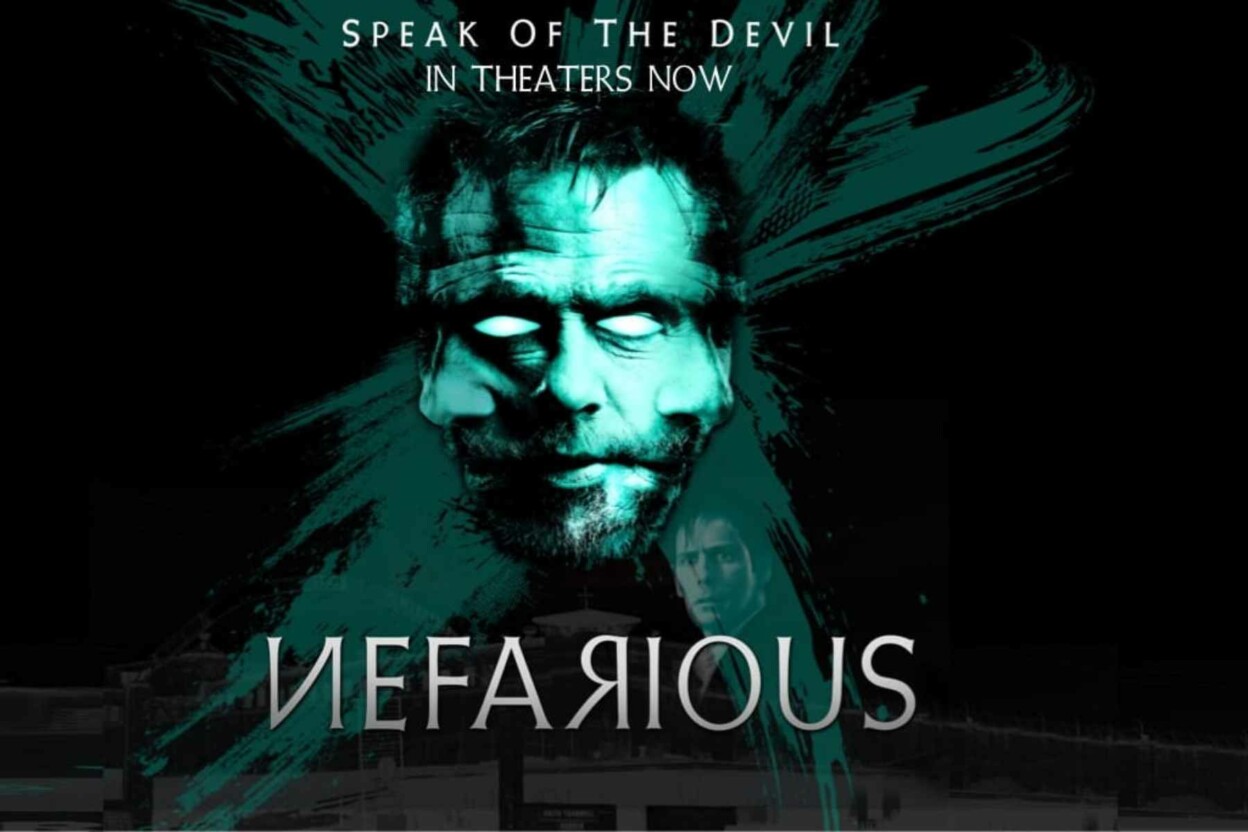

With the steady drip-drip of movies from “The Conjuring” Universe, the revival of “The Exorcist” franchise with “The Exorcist: Believer,” two Russell Crowe-headlining exorcism movies in as many years (“The Pope’s Exorcist” and “The Exorcism”), one faith-based exorcism film made by the writers of the “God’s Not Dead” movie (“Nefarious”), Lee Daniels’ “The Deliverance” on Netflix and the Mike Flanagan’s “radical new take” on “The Exorcist” franchise, there certainly seems to be some sulfur in the air in Hollywood.

So what’s going on?

The likely reasons actually say a lot about the present and the future of religion in America and its intersection with the future of mass media.

Follow the money

The first reason is undoubtedly because Hollywood likes money — and they are sure there’s money in exorcism movies. After all, the first “The Exorcist” film back in 1973 (which had its 50th anniversary last year) was a box office and critical juggernaut, searing itself into the American cultural psyche.

In an era when Hollywood is trying to find its next big genre, and where horror films are having a renaissance, making exorcism movies is a no-brainer.

Related to this, but still of note, is that nobody has truly cornered the market on exorcism movies yet. There aren’t enough of them to crowd out others from joining the fray. Therefore, everyone thinks that they can maybe be the one to crack the code. While “The Conjuring” franchise has made money, it certainly hasn’t made so much as to crowd out the competition — at least in the eyes of Hollywood producers.

Think about “The Pope’s Exorcist,” which portrayed Russell Crowe as a wise-cracking, motorcycle-riding priest and had an ending that set up a bunch of demons he and his partner needed to go after — a move clearly meant to set up a franchise. Or “Exorcist: Believer,” for which Universal paid $400 million for the rights to “The Exorcist” franchise as part of a planned trilogy before bad reviews (including mine) and a bad box office led the company to pivot, with Mike Flanagan hired for the next one as part of a “radical new take.”

Rising interest

The second reason is likely that interest in exorcism is itself having a cultural renaissance. America’s rising Hispanic population is part of it. This demographic really likes horror films — particularly about exorcisms, like “The Conjuring” franchise. A big reason is because Hispanic Americans are so strongly Catholic, and exorcism movies are strongly Catholic, too.

But it’s not just Catholics who love exorcism films. One of the few growing Christian denominations in America is Assemblies of God. It is part of the Protestant Pentecostal sphere, which emphasizes things like prophecy and what it calls “deliverance” — the denomination’s term for exorcism. This is translating into box office receipts. The in-house documentary about Greg Locke’s rising deliverance ministry, “Come Out in Jesus’ Name,” grossed $2.5 million on a budget of $400,000. It was one of distributor Fathom Events’ best-performing movies of the year, despite only playing for three nights.

The shrinking of Catholicism and the rise of Pentecostalism is one reason why many exorcism movies are moving toward representing the latter. “Exorcism: Believer” had Pentecostals partnering with Catholics to fight the demon. “The Deliverance” outright puts Pentecostals at the center of the fight. They use the language of deliverance, use the terminology of “strongholds” and speak in tongues. They even outright call out this contrast between them and the more Catholic portrayal of demon-fighting in mass media.

Another difference in the Pentecostal and Catholic traditions is that women can be priests. So movies like “The Exorcist: Believer” and “The Deliverance” do more to put women at the center of demon slaying. In fact, in “The Deliverance,” it’s all women doing the demon-slaying.

Rewriting religion

The final reason is because we’re in the middle of a cultural rewriting of spirituality. Contrary to popular belief, younger Americans are not becoming more atheistic. According to Pew Research in 2023, most “nones” continue to be spiritual and believe in some higher power. They simply reject organized religion as a way to get there.

As Tara Isabell Burton wrote in her 2020 book, “Strange Rites: New Religions for a Godless World,” institutionalized religion is being replaced by whatever feels right to the individual. Dr. Jean Twenge, author of the book “Generations,” summed up the challenge to traditional religion this way: “In short, because it is not compatible with individualism — and individualism (is) Millennials’ core value above all else.”

However, as Carl Jung noted, you can’t simply create meaning. You have to pull meaning from what already exists. So inevitably, when people try to create a new spirituality, they have to pull on the old ideas and remix them rather than simply create something fully new.

Writer M.A. Fortin admitted to Variety this was the thinking behind this year’s film “The Exorcism,” both for him and for his personal and creative partner Joshua Miller, who co-wrote and directed the film. Miller was also the son of actor Jason Miller, who played the priest Damien Karras in the original “The Exorcist.”

“The language of exorcism movies suddenly felt weirdly compelling to us — the fact that they’re all the same sort of verse, chorus, verse, where the Catholic Cortana is inviolable, perfect and it will save you,” he said. “Also, women are always the ones you know who are going to be possessed because they’re receptive — it’s very sexist. … It made us wonder how we could f–k around with the exorcism genre. Also as queer people, we’ve been a couple for 20 years, and I specifically had some nuns in my background for a hot minute. I’ve always had a tenuous relationship with the church and with its relationship towards queer people.”

You see this remixing of spirituality in a lot of the recent exorcism movies. In “The Exorcism,” it’s the father who plays the priest — and is a real priest — who is possessed, and it’s his gay daughter who must save him. In “The Exorcism of St. Patrick,” a priest kills a gay boy in a conversion therapy attempt gone wrong, and then he gets haunted.

Movies like “The Exorcist: Believer” and “The Deliverance” both put women at the forefront of exorcism, having them be the experts in the field and — in many cases — making them the heroes rather than the victims. Likewise “The Conjuring” movies have a husband-and-wife team as equal partners in the hunt for evil spirits. These are primarily Catholic works — but a pro-LGBTQ and feminist take on them rather than leaning into the Pentecostal tradition where such things are deemed normal.

The future

Exorcism films will continue as Hollywood tries different versions until it finds one that audiences embrace the way they want it to. That will then be the model going forward. There are, however, complications to that ever happening.

The first is that the ever-individualizing trend toward spirituality will make it increasingly difficult for a movie about exorcism to resonate with a wide enough segment of the population — particularly as Hollywood movies try to remix their movies away from more traditional interpretations of religion to be more in line with modern sensibilities. Political progressives who will like the LGBTQ+ themes of “The Exorcism” won’t relate to its portrayal of religion since they already have their own spirituality perfectly tailored to suit themselves.

This means that the traditional faithful will be the largest audience with a unified version of faith that a Hollywood movie could represent and resonate with. And yet Hollywood — being so divorced from these communities — has difficulty in making such movies that the audience does resonate with. (See my article here). It also has the problem that many religious audiences don’t like horror movies in general. (See my article here).

This is not just true of horror films, but of movies in general. Dr. Jonathan Haidt argues in his book “The Anxious Generation” that the internet and smartphones have so fractured us into individualized narratives that we no longer have overarching meta-narratives to share. As the church declines, movies remained our shared cultural narratives. But the internet and streaming have pulled us away from those as well. Soon, religious people will be the only ones with unified narratives because they go to services and share in them.

This presents an opportunity for faith-based filmmakers. People who can speak the language of both faith and film will be in high demand as the people most capable of speaking to one of the only audiences will have a unified meta narrative. And because that unified meta-narrative is specifically religious, the stories being told will likely be more overtly religious as well. (I made a similar argument about the future of Christmas movies here).

Exorcisms are a part of America’s cultural landscape and no doubt part of its future as well. Time will tell who will tell the stories that define how we understand the practice for the next 50 years.