Martin Luther King III on MLK Day: ‘We have a lot of work to do’

The 2025 inauguration falls on the same day as MLK Day this year. Martin Luther King III reflects on the state of the nation.

It was Martin Luther King Jr. who had the dream.

But it was the pop songwriters of the 1960s who set it to music. And a few brave TV producers who put it on the tube. And a few exceptional Hollywood actors who embodied it on screen.

The 1960s civil rights movement was galvanizing. King, whose birth we celebrate as a national holiday this Jan. 20, was — along with Rosa Parks, John Lewis, Fannie Lou Hamer, Bayard Rustin and many others — throwing down the gauntlet.

But who would stand with King? Who would rise to the occasion? Students did. So did the clergy. And so, in the early 1960s, a few committed artists and entertainers, as well.

“You’re starting to see Black people coming into your home through the television, and Black music through AM radio, and the superstar phenomenon of Sidney Poitier in movies,” said Michael Dennis, a Philadelphia filmmaker and film promoter.

For a roughly 13-year period, from the mid-1950s until King’s assassination in 1968, pop culture became a conduit for the ideas of equality, freedom and tolerance.

Through it, such ideas filtered into the lives of millions of ordinary people. Brotherhood was in the air in the early 1960s — and at least some of that had to do with the movies, songs and TV shows of the period.

“I think a lot of the ideals that Martin Luther King was promoting found their way into the culture through film and music,” said Dennis, whose Reelblack TV YouTube channel is an archive of Black film ephemera, and also a platform that explores issues of Black representation and culture. “It was kind of a perfect storm.”

Hollywood led the way

Hollywood was first out of the box.

The groundwork had been laid, even before MLK. Documentary shorts like “The Negro Soldier” (1944), part of Frank Capra’s “Why We Fight” series, were a key part of the World War II propaganda effort. The message was: “We’re all in this together.” “The Office of War Information in the 1940s, along with the NAACP, mandated that there be more positive images of Black people in American films,” Dennis said.

When the war ended, and it turned out we weren’t all in this together — when Black survivors of World War II returned to the same prejudice and segregation they had left — the civil rights movement abruptly kicked into high gear. Some of the same Hollywood talents who had worked on government propaganda films have now turned their attention to this new cause.

“Home of the Brave,” “Lost Boundaries,” “Pinky” and “Intruder in the Dust,” all released in 1949, were among the “problem pictures” that tested the waters. But things amped up dramatically in 1955 — when the Montgomery bus boycott brought both Rosa Parks and Martin Luther King Jr. into the spotlight, and the murder of Emmett Till was seared into America’s consciousness by the horrific photos in Jet magazine.

“The fact that they ran those uncensored photos of Emmett Till awakens everyone who might otherwise be asleep, Black and white, as far as what’s going on in the country,” Dennis said.

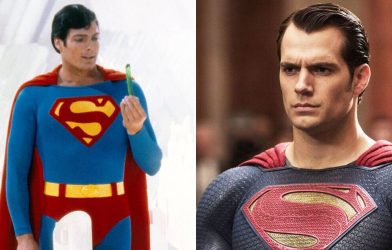

The times called for a Black hero. And Sidney Poitier — improbably handsome, impeccably dignified, superhumanly poised — was the guy.

“He’s sort of the film equivalent of Jackie Robinson in sports,” Dennis said. “He becomes the emblematic symbol of what we should all aspire to as Americans, as Black people, as human beings.”

Poitier to the rescue

He’d been in movies since 1947. But in 1958, under the direction of Stanley Kramer — like Capra, a U.S. Signal Corps veteran — he made a movie called “The Defiant Ones” that was a track for the times.

Poitier and Tony Curtis are escaped convicts. Poitier is Black. Curtis is white and a racist. And — here was the gimmick — they’re chained together! They have to learn to get along. Just like all of us! It was the perfect civil rights era message — though, as James Baldwin reported, Black audiences actually booed the big finale, when Poitier tries to save his racist cellmate. Like that would happen.

In film after film, Poitier brought MLK’s integrationist message to mixed audiences. To African American viewers, who were happy to see a dignified Black star. To white viewers, who were delighted to think they’d have no problem with this paragon moving next door to them.

In “A Raisin in the Sun” (1961), Poitier just wants to move his wonderful family to the suburbs. “We don’t want to make no trouble for nobody or fight no causes,” he says. In “A Patch of Blue” (1965), he becomes friends with a young white woman (Elizabeth Hartman) who literally doesn’t see race — because she’s blind! “I know everything I need to know about you,” she says.

All of this was in step with the MLK message. In these early ’60s films, everyone was judged not by the color of their skin, but by the content of their character. Everyone sat down together at the table of brotherhood.

Naïve as they might seem now, these films caught a mood. Like King’s “I Have a Dream” speech, they were hopeful. A prayer that America might somehow, finally, get this right.

Poitier’s success — certified by a Best Actor Oscar for “Lilies of the Field” (1963), the first for a Black performer — helped pave the way for stars like Ruby Dee, Ossie Davis, Diana Sands and Cicely Tyson. And when Poitier marched along with other celebrities, Black and white, in the 1963 March on Washington — including Marlon Brando, Harry Belafonte, Burt Lancaster, Charlton Heston, Lena Horne and Paul Newman — it seemed to some as if the millennium had arrived.

“By 1967, Poitier is the No. 1 box office star in the world probably,” Dennis said. “He’s at the pinnacle of his powers at that point.”

Freedom songs

But while movies might help set the table for the civil rights movement, an even more direct route to America’s heart, in the early 1960s was through its transistor radios.

During this period, Ed Sullivan starts inviting stars like Sam Cooke (1957), The Shirelles (1961) and The Supremes (1964) into people’s homes. In itself, an important step.

But such performers were always carefully groomed for mainstream America. The Motown ladies actually went to charm school. Certainly, none of them, on TV or on their records, referred in any way to the issues that were galvanizing America: the sit-ins, the marches, the firehoses being turned on children.

That would change.

On Oct. 8, 1963, Sam Cooke (“We’re Having a Party,” “Twistin’ the Night Away”) was turned away from a Holiday Inn in Shreveport, Louisiana. He protested — and was arrested. “Negro Band Leader Held in Shreveport,” read the UPI headline.

The incident lit a fire under him. By Christmas 1963, he had written a new song. It was unlike anything he’d ever done. People cautioned him against it. But “A Change is Gonna Come” (1964) was a watershed — not just for him, but for pop music. It was among the first to refer explicitly to segregation — and to imply, in the title, that its days were numbered. “I go to the movie, And I go downtown, And somebody keep telling me, Don’t hang around — It’s been a long, a long time coming, but I know, A change gon’ come.” Cooke put all of the soul of a former gospel singer into it.

Get on board

Meanwhile, Curtis Mayfield, frontman for The Impressions, gave both “Keep on Pushing” (1964) and “People Get Ready” (1965) a churchy feel. But listeners knew what he was really singing about. “A great big stone wall stands there ahead of me, But I’ve got my pride, And I’ll move aside, And keep on pushin’.’” Both songs were used at civil rights rallies to fire up the crowds.

“‘Keep on Pushing’ is almost literal. It’s talking about a struggle, and not giving up,” said Dennis Diken, a music historian and drummer for the seminal indie-rock band The Smithereens.

“‘People Get Ready’ is even more overtly gospel,” said Diken, a Wood-Ridge resident. “It can be interpreted as a save-your-soul kind of thing, but I think it’s got a social consciousness to it. I think anybody with half a brain is going to get the message. Maybe not the teeny-boppers. But anybody who was astute.”

These songs, along with protest anthems by folk stars like Bob Dylan (“Blowin’ in the Wind,” 1962) and broadsides by jazz stars like Nina Simone (“Mississippi Goddam,” 1964), are the soundtrack of the civil rights era. And as the decade went on, more were added to the setlist: “Respect” (1967) — Aretha Franklin was superficially singing about sex relations, but the “R-E-S-P-E-C-T” had a broader meaning — “Eve of Destruction” (1965) by Barry McGuire, “Society’s Child” (1966) by Janis Ian, “We’re a Winner” (1968) by, again, The Impressions.

Even Elvis got into the act: “If I Can Dream” (1968) and “In the Ghetto” (1969) were his late-’60s bids for relevance. Not just the songs but also the production in that era were influenced by the spirit of MLK. Stax and Muscle Shoals were among the studios of the era that prided themselves on having an integrated roster.

The final frontier

And then there was TV — traditionally the most conservative mass medium, the one most cautious about offending. Yet the MLK era seemed to demand something more. So — conservatively, cautiously — it took baby steps.

Rod Serling was one of the pioneers. At least four episodes of “The Twilight Zone” showcased Black performers; they won Serling a Unity Award in 1961. “Gunsmoke” and “Bonanza,” two of the most popular Westerns of the mid-’60s, had “race” episodes.

More significantly, “I Spy,” which launched Bill Cosby’s career, became in 1965 the first show with a Black co-star. It was followed in 1968 by “Julia,” making Diahann Carroll the first Black woman to star in a series. All these shows, in small ways, helped increase white Americans’ acceptance of the idea of Black Americans as fully equal members of society.

But there was one show that actually engaged the attention of Martin Luther King Jr. himself.

“Star Trek” (1967) had a pointedly interracial cast. Lt. Uhura (the late Nichelle Nichols) was among the crewmembers of the Starship Enterprise — one of many ways the show went Boldly Where No Man Has Gone Before. Yet Nichols, as the first season wore on, began to fear that her character was only a token. She considered quitting. It was King, she said, who talked her out of it. He was a Trekkie.

“You cannot, and you must not,” Nichols, in her autobiography, recalled his saying. “Don’t you realize how important your presence, your character is? … You have the first non-stereotypical role on television, male or female. You have broken ground. For the first time, the world sees us as we should be seen, as equals, as intelligent people — as we should be.”

End of an era

So what happened to this kumbaya moment in pop culture?

It had begun to dissipate even before King’s tragic assassination at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis on April 4, 1968.

A less conciliatory wing of the civil rights movement was gaining ground. In 1967, race riots broke out in Newark, Detroit and other cities. The Turn the Other Cheek persona of Sidney Poitier — of MLK — was starting to seem cringey to some.

You might say the story ends as it began, with Poitier. When Larry Gates, the bigoted plantation owner of “In the Heat of the Night” (1967), slaps him, Poitier — famously — slaps him back. “That slap ushers in a new era,” said Dennis of Reelblack TV.

The pop songs of the Black Power years, like “Say It Loud — I’m Black and I’m Proud” (1968), would be in-your-face. So would the movies. “Shaft” (1971) and “Superfly” (1972) would not be helping nice white nuns build churches in the desert. That “Lilies of the Field” scenario belonged to a different, more innocent era. An era that ended abruptly on April 4, 1968.

“Audiences are demanding more from their Black leading men,” Dennis said. “They want, if not retribution, then someone who is going to stand up for themselves.”

Turner Classic Movies will be featuring civil rights-era Hollywood films throughout Martin Luther King Day, Mon. Jan. 20. Among them: “A Patch of Blue” ( 6 a.m.), “Lost Boundaries” (12 p.m.), “Intruder in the Dust” (2 p.m.), “A Raisin in the Sun” (3:30 p.m.), and “In the Heat of the Night” (12:15 a.m. Jan. 21).