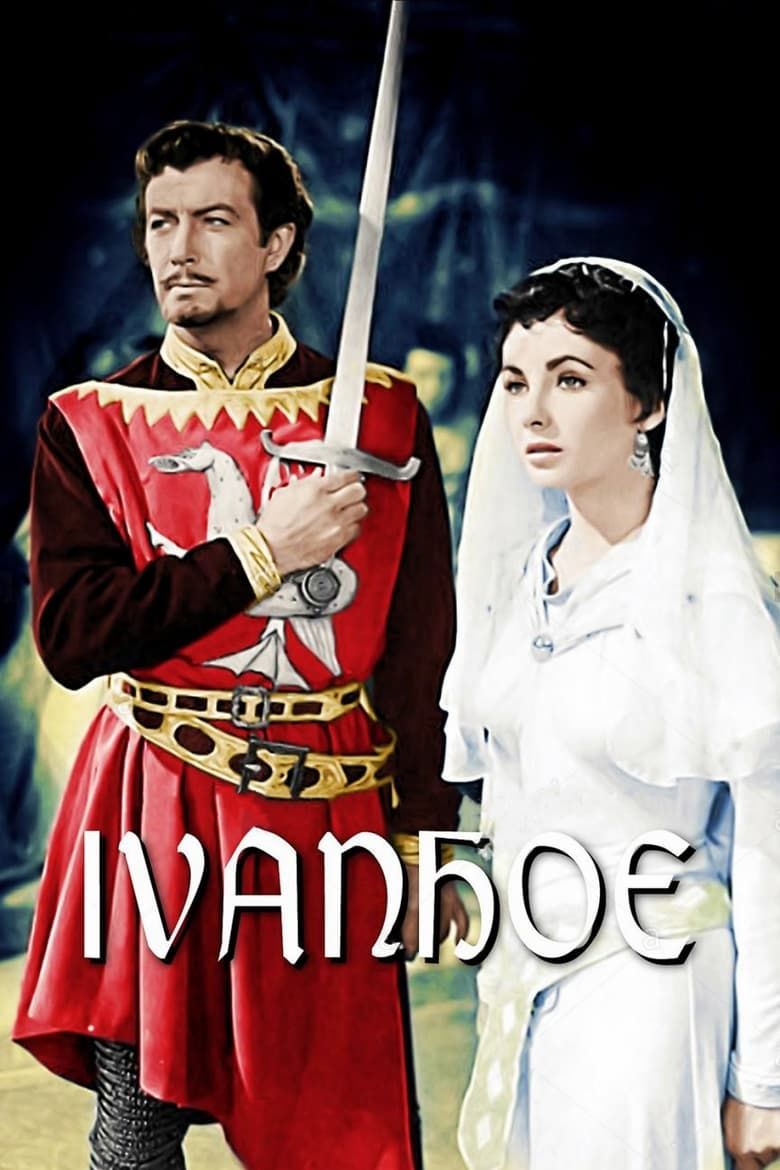

It’s hard to believe there was a time when films set during medieval times were bright and colorful as opposed to dark and gloomy, yet that was the default in a pre-Game of Thrones world. Stories of kings, queens, knights, and squires were reliable moneymakers during Hollywood’s Golden Age, providing escapest entertainment for eager audiences. A film like Ivanhoe, released in 1952, feels almost quaint by today’s standards, but its splashy Technicolor trappings remain a necessary antidote to troubled times, in much the same way it was back then. And like most movies released during the Hollywood Blacklist, there’s a surprisingly political undercurrent to this swashbuckling yarn.

‘Ivanhoe’ Was Bright Entertainment During One of Hollywood’s Darkest Periods

Adapted from the 1819 historical novel by Sir Walter Scott, Ivanhoe stars Robert Taylor as Wilfred of Ivanhoe, a wandering knight on a quest to return the missing Norman King of England, Richard the Lionheart (Norman Wooland), to the throne. As Richard is being held for ransom, his treacherous brother, Prince John (Guy Rolfe), rules over the country with the help of his loyal knight, Sir Brian de Bois-Guilbert (George Sanders). Ivanhoe pleads with his estranged father, Cedric (Finlay Curie), to pay Richard’s ransom, but as a proud Saxon, he refuses to aid a rival Norman. Ivanhoe, meanwhile, romances his father’s ward, Lady Rowena (Joan Fontaine), and frees his jester, Wamba (Emlyn Williams). When he is wounded during a jousting contest with five of Prince John’s knights, Ivanhoe is hidden by Robin Hood (Harold Warrender) and his merry band of thieves. He’s healed by Rebecca (Elizabeth Taylor), the beautiful daughter of the Jewish Isaac of York (Felix Aylmer), who’s accused of being a witch for possessing “magic powers.” After leading the Saxons to victory, Ivanhoe duels De Bois-Guilbert to save Rebecca from burning at the stake.

Although its screenplay was solely credited to Noel Langley and Aeneas MacKenzie, Ivanhoe had a third screenwriter, Marguerite Roberts, who originally went un-credited. That’s because Roberts, a steady hand at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer who had written such titles as Dragon Seed and Ziegfeld Girl, was blacklisted after she and her husband, fellow screenwriter John Sanford, refused to name names to the House Un-American Activities Committee. Taking a principled stand cost Roberts not just her credit on Ivanhoe, but also her contract at MGM. It took nine years for Roberts to land another credited screenwriting job on the socially-conscious drama Diamond Head, and she later wrote the John Wayne Western True Grit.

Related

The Production of Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor’s ‘Cleopatra’ Was a Glorious Disaster

Hollywood’s troubled epic still struggles to emerge from the cloud of its own reputation.

The lingering effects of the red scare put Ivanhoe in a special category with another 1952 release: the Western drama High Noon. As written by blacklisted screenwriter Carl Foreman, the story of a marshal (Gary Cooper) who’s forced to stand alone when a gang of bandits rides into town was an overt allegory to the dangers of HUAC, and the importance of doing the right thing in the face of certain doom. Although it’s far from a left-wing screed, Ivanhoe nevertheless reflects a similar point of view, as the hero fights back against powerful forces to save the downtrodden. Ivanhoe’s quest to return Richard to the throne has less to do with loyalty to the monarchy and more to do with helping those who are being oppressed by Prince John: the Saxons, the poor, and the Jews.

‘Ivanhoe’ Is a Rousing Tale of Adventure

When it was released in 1952, Ivanhoe was a box office hit, spawning two unofficial sequels that reunited star Taylor, director Richard Thorpe, and producer Pandro S. Berman: 1953’s Knights of the Round Table and 1955’s The Adventures of Quentin Durward. Yet none could match the original, which New York Times critic Bosley Crowther called a “brilliantly colored tapestry of drama and spectacle.” The film was such a success that it earned Oscar nominations for Best Score, Best Cinematography, and Best Picture, where it competed against High Noon (both lost to The Greatest Show on Earth, long regarded as one of the worst winners in history).

Perhaps Ivanhoe struck such a chord with critics and audiences because, like the Errol Flynn adventures of yore, it brightened the country’s mood when it needed it the most. While Flynn’s films (The Adventures of Robin Hood among them) delighted audiences during the Great Depression and World War II, Ivanhoe lifted spirits as the Cold War continued to escalate. At a time when our national disposition is once again at an all-time low, it’s perhaps needed now more than ever.

Ivanhoe

- Release Date

-

July 31, 1952

- Runtime

-

106 minutes

- Director

-

Richard Thorpe

- Writers

-

Marguerite Roberts

- Producers

-

Pandro S. Berman

-

-

Robert Taylor

Wilfred of Ivanhoe

-

-

George Sanders

De Bois-Guilbert