He does it, right there in the hook section of the now globally-trending OTT release of “Heeramandi”; Sanjay Leela Bhansali announces that he is sticking to his own typical Bhansali Productions walla Gender politics on the screen. In the first episode, within the very opening scene is a transphobic dialogue exchange, they couldn’t even wait for the hook section to be complete. Following this is another in which Sonakshi Sinha’s character uses the derogatory word Khusra, complete with clapping to indicate that to be Khusra is the worst.

The hook section lets you know SLB is going to tell you a 20th century patriarchal story with Gender portrayed through a limited 21st century, Savarna male-gaze that by now we are all too painfully familiar with. Remember Padmavat and the glorification of Sati (custom of a Hindu widow burning herself to death or being burned to death on the funeral pyre of her husband) we doing that – now on OTT with Tawaifs. The final closing scenes of both films are thematically and, to an extent, visually similar in their glorification of feminine sacrifice for love and for the land.

I managed to binge through the entire show this past weekend. I happen to have a keen interest in the subject matter and the time period this film was set in, as I am currently researching it for another project. I have done a fair amount of research on the subject and firstly I am here to tell you that Heeramandi, does not actually get it entirely wrong all that much. In my opinion it does do some justice in showcasing the part that The Tawaif played within the freedom struggle.

Also importantly as a Muslim woman, I was both shocked and honestly grateful for the Muslim representation in Heeramandi. I mean, Baijayanti Roy actually wrote a research paper in Goethe-Universitat titled Valorous Hindus, Villainous Muslims, victimized women: Politics of identity and gender in Bajirao Mastani and Padmaavat. That’s how Islamophobic Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s past works have been.

It was honestly shocking and refreshing to see the acknowledgement of Muslims within the freedom struggle and also the incredible scene where Bibojaan (Aditi Rao Hydari) shoots a British Officer with a pistol while wearing a Burqa. In another scene, the Kalma is read out loud on screen upon the death of a Muslim freedom fighter. While, on the whole, the effect of the typical over-the-top feels will end up only playing into the otherization (and orientalisation) of Muslims, there seems to be some real efforts made here to incorporate a general Muslimness into the story and the freedom struggle.

The Blatant Transphobia and Homophobia and Heeramandi:

For me, like Vinay Nirmala said, the queer portrayal of it made me want to “abuse so f#$#ing much.” It was the same old done-to-death bollywood portrayal of queer characters. Geet observed that the whole Ustaad character is just problematic. Ustaad is either intersex, transgender or a cisgender gay man, none of which is clarified, and also I think the difference between the three is entirely lost on the filmmakers. Ustaad is a sort of pimp in this world, I say sort of, because pimps were seen quite differently during this time period. They are shown as duplicitous, snake-like and untrustworthy.

Meera Singhania put it very eloquently, “It’s a very “oriental”, colonial trope to look at queer characters.” It portrays it’s queer characters and also queer love, through the colonists lens of victorian morality. The British are the ones who passed the Criminal Tribes Act and pushed this idea that transgender folks are horrible, disgusting and criminal. And today folks like Sanjay Leela Bhansali continue to portray us as seen through that colonized portrayals on screen.

In two instances Sanjay Leela Bhansali uses Queer sex on screen to build a certain character profile. The way he does it ends up stigmatizing queer love within the existing stereotypes. As somehow unnatural. In one scene SLB needs us to begin to dislike this British officer, Cartwright, who is to be one of our main antagonists going forth. How does he do it? By showing this british officer to seemingly rape Ustaad. We never see any other intimate scene in the entire show with the character Ustaad. In this scene the queer sex is used as a device to build negative associations. In another scene we see Fareedan (Played brilliantly by Sonakshi Sinha) about to sleep with a woman, and here this scene is shown to build both Fareedans’s duplicitous nature, and sort of “femme fatale” like character.

And with Sanjay Leela Bhansali this is something of a habit, we’ve seen him present transphobic transgender characters before like Razia Bai in Gangubai Kathiawadi and Malik Kafur (a real historical figure) in Padmavaat.

The Whole Memoirs of a Geisha of it all

Besides the homophobia and transphobia, what is also annoyingly frustrating for me, is just how shallow and male gaze-y it gets with gender politics. It’s the whole Memoirs of a Geisha of it all it it’s treatment of The Tawaif culture.

Sampada Sharma wrote for Indianexpress, “It may appear as though these women are being celebrated but they are treated like sacrificial lambs who are made to believe that their sacrifices have some kind of meaning.

Bhansali makes the idea of ‘sacrifice’ appear noble, without actually inspecting how these women are being tortured over and over again, and never reaching any point of salvation. There was a time in Indian cinema, when female characters were portrayed as bechari abhla naaris’. The female characters in the alpha-male movies existed as wives or sisters or mothers, and were there only to serve the men of the story. They were repeatedly taught to sacrifice themselves for their family, and society but then we moved forward. Female characters started getting independent, having more agency and were not just seen from the lens of the male characters of the story, and as audience, we loved that change. Much like the women, men too started evolving in the movies but now it’s starting to feel like the clock is turning back.”

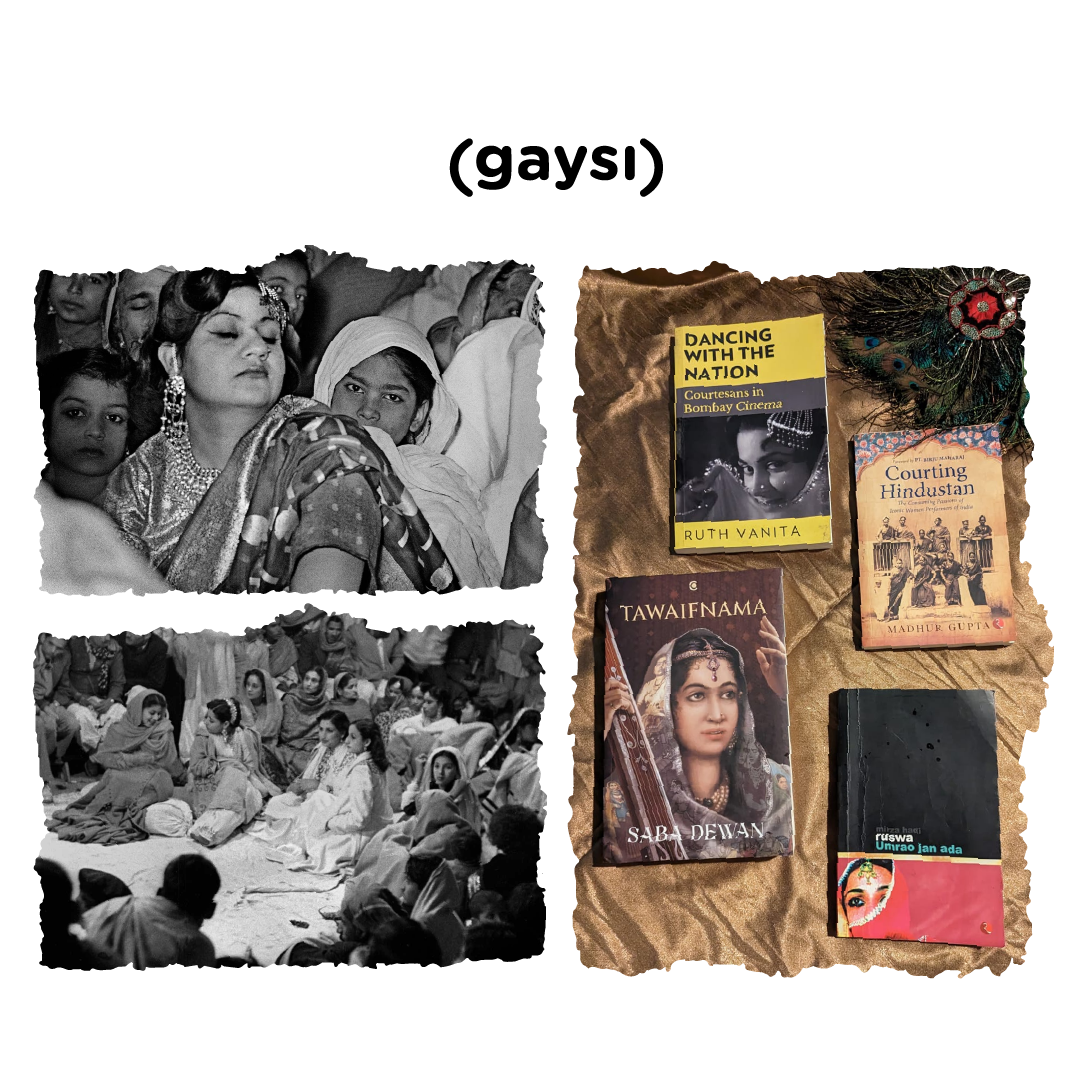

When you read about the Tawaif through Sabah Dewans’ gaze in ‘Tawaifnama’ (a Muslim women), or Ruth Vanita’s gaze in ‘Dancing with the Nation’ (a transgender woman) there is so much more to it. The truths, the joys, the pain, the struggle and most importantly the empathy. Their works seem to always come back to bringing focus to THE PATRIARCHY THE PATRIARCHY THE PATRIARCHY.

Sabah Dewan is a Documentary film-maker. Her documentaries and books have focused on issues of gender, sexuality and culture. The Mint said of her book, ‘As a historical text, it is a feat. Dewan bridges generations of private memories with public archives to compile a thorough and tender account of tawaif life. Most significantly she approaches – and pay attention to this – a 20th century culture with the nuance of 21st culture gender politis.’ – Mint

Somehow when you read Madhur Gupta (leading odissi dance Maestro) Courting Hindustan, or for that matter my much beloved Umrao Jaan Ada by Ruswa (male poet, born in the year that Kingdom of avadh collapsed) or its onscreen Indian or Pakistani renditions (yes two exists and I’ve watched em both) – Much like Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s brand new Heeramandi – they all almost never seem to call out the Patriarchy or even gender as a social construct as these other feminine and feminist gazes.

That’s my fascination with the subject in case you were wondering. The Tawaif, the Hijra and The Khawaja Sira all existed at the same time in our collective South Asian history.

They all inhabited gender in a very interesting way, and really a way that we have not seen since in our lands. The Tawaif like The Geisha existed within patriarchal societies where their entire reason to be seems to be to inhabit GENDER in a generationally learned and intentional manner publicly. To socially perform the construct GENDER. They had involvement with spirituality and religious festivals, culture and performance arts, and education. Some of them were cultural stalwarts of their time, and for various reasons were known by a lot of folks. Albeit I would gather given class and caste differences within the larger population that inhabited these lands, you would be surprised to know that you didn’t have to know too many to be famous. I mean I’m sure these days just the Instagram followers of Shaikh Khushi would quadrupole or more, idk, I suck at math – the number of “followers” that Begum Hazrat Mahal ever had in the time that she was alive for instance.

The issue for me, and also annoyance, is It is unlikely that Sanjal Leela Bhansali or Muzaffar Ali (Umrao Jaan) in their renditions of Tawaif cultures ever intend to bringing your attention to oppressiveness nature of performative gender in Patriarchal systems. On contraire SLB seems to want to continue to celebrate the sacrificial women.

There are films that do justice, where we have seen women who we can relate to and aspire to be. More often than not, like Dahaad, Lipstick under my Burkha, Bhakshak and Lapataa Ladies writers are mostly women or co-written by women. Now I’m not saying that men can’t inhabit the feminine gaze, there are surely some examples for that like Anubhav Sinha for Thappad. But more often than not like Sampada Sharma points out these days it’s starting to feel like the clock is turning back – The Pushpas, KGFs and the Animals of the last few years have brought back the alpha-man and Heeramandi has brought back the sacrificing woman, which isn’t a cause for celebration.

I have to ask:

Answer me honestly, would you say after watching Heeramandi, that Sanjay Leela Bhasali – Music, Direction, Screenplay – approached a 20th century complex patriarchal culture with the nuance of 21st culture gender politics.’

Just move over and make some space please, why thank you very much.