‘A woman without her husband is like boiled rice: bland, unappetising, useless’ – Fire, 1996.

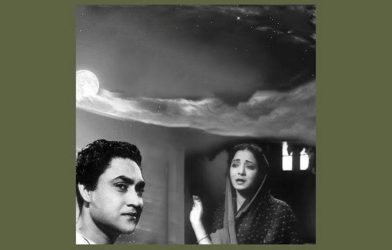

It’s one of many quotes from Deepa Mehta’s trailblazing Bollywood movie that cuts to the heart of women’s self-autonomy in 1990s India and echoes with the generations since who have face the same barriers in their own conservative households.

In the movie, newly-married housewife Sita (Nandita Das) confides this mantra she grew up with to her sister-in-law Radha (Shabana Azmi) who wryly replies: ‘I like boiled rice.’

A simple response on the surface but look underneath and it’s saying ‘don’t worry. I’m a kindred spirit’. In other words, a lifeline for women trying to feel less lonely as they break out of the echo chambers they’ve been reared in.

The film follows Sita’s fresh arrival into her husband’s household, where he lives with his mother, brother and his wife (Radha).

As we watch the early days of their marriage unfold, tensions begin to brew as the dynamics between our characters start to shift, break and blossom between Sita and Radha.

Among sapphic South Asians, Fire holds a revered legacy. It’s spoken about in hushed whispers among baby queers seeking that sweet representation in people who look like them.

It’s the classic movie at the top of your ‘beginner’s guide to being a gay South Asian woman’. It’s the movie you check off your list when delving into the rich world of queer cinema.

Join Metro’s LGBTQ+ community on WhatsApp

With thousands of members from all over the world, our vibrant LGBTQ+ WhatsApp channel is a hub for all the latest news and important issues that face the LGBTQ+ community.

Simply click on this link, select ‘Join Chat’ and you’re in! Don’t forget to turn on notifications!

And for good reason – it’s one of Bollywood’s first-ever mainstream movies to depict a same-sex relationship between two women.

After premiering in 1996 at the Toronto International Film Festival – from Indo-Canadian filmmaker Deepa – the movie made its way to home turf in 1998, instigating a hubbub across the political spectrum.

Despite its shock clearance with the Indian Censor Board (who believed this film was a vital watch for women in India) certain screenings of the movie were attacked by right-wing Hindutva mobs forcing the movie to be pulled from Mumbai and New Delhi.

There were threats delivered to the doors of those involved in the project and intimidating demonstrations – the usual volatile decrying from those against progress.

But among the disruption, there was a fiery response from counter-protestors and women coming out in droves to make the movie a hit.

What’s more, the disruptive saga around its release cemented Fire’s place in modern Indian history – offering karmic justice to the naysayers and a piece of juicy cultural debate for those wishing to unpick the themes on an intellectual level.

The first time I saw a queer Bollywood film was the 2019 movie, Ek Ladki Ko Dekha Toh Aisa Laga, which I imagine served the same purpose for my generation as Fire did for the last.

It was the movie on everyone’s lips and, although it was coming out over two decades after Fire, was still one of just a handful of Bollywood films depicting a lesbian relationship.

I remember watching it on my laptop one evening and feeling a spark of excitement at the very fact this movie existed (and was big enough to stir interest in people who hadn’t even considered South Asian sapphic relationships before).

As well as an overwhelming sense of calm that maybe everything would be OK after all.

I imagined the countless women watching Fire for the first time who felt the very same.

It was six years later that I would watch Fire, once more on my laptop, but this time as a far more confident version of myself. And yet the poignancy and beauty of the movie was only enhanced by my self-empowerment.

The rice exchange is just one of several beautiful moments Sita and Radha share. Both trapped in loveless marriages their bond naturally develops and turns into something more.

I felt goosebumps during one scene when Radha offers to put oil in Sita’s hair, an intimate gesture so culturally specific (I had never seen sapphic love portrayed like this) that I had to pause for a moment to tamp down my joy.

We hear of Radha’s childhood dreams to one day see the ocean, we watch the spark of rebellion in Sita grow as she becomes disillusioned to her situation.

At one point she is forced to wash blood from the sheets in the silence of the night after losing her virginity while her husband sleeps on beside her.

In another scene, Sita dresses up in a suit and dances with Radha in the living room – both lost in a daydream of what their lives could be like.

It was refreshing to see that the film didn’t allow for this love to grow between the lines, however, and there is more than one intimate scene where they share one another’s bed.

When the film first aired in India, it was not only lauded for its queer representation but also for its ability to connect to any woman trapped in a lonely marriage – and it achieves that beautifully.

It’s about female desire and the unspooling of archaic structures.

In 2008, Mehta recalled the vigil held by the LGBTQ+ community in Dehli when this movie came out: ‘They carried placards saying, “We’re Indian, we are Lesbian.” Till then some Indian moralists believed homosexuality, especially lesbianism, didn’t exist in India.

‘Fire was a turning point for me as a filmmaker. I saw what responsibility was being put on my shoulders. To me, Fire wasn’t a film only about lesbianism.’.

There has also been some criticism at the lack of sexual chemistry between the characters over the years and while at times it did fall flat, the fact it even goes there is triumph enough.

Fire is far from perfect, there’s valid criticism of how authentic their love story is given they are two women who have simply found comfort in one another under the same toxic roof.

But its shortcomings wane in the face of all it has come to mean – fanning the flames of radical representation in Indian cinema and resonating with diaspora around the world for years to come.

My favourite moment comes at the end when the home goes up in a blaze and, as the ashes settle, both our protagonists are doused in water – a nod to Radha’s dreams of the ocean air.

But far from my fears that both would perish or be brutally torn apart (as was quintessential for 90s queer media) we have a soft and sweet reunion.

A rare happy ending that echoes a timeless message of hope for a brighter future.

Perhaps there are better films out there but there’s a reason Fire remains a cultural staple, and is the blueprint for so much that came after it.

If there’s one movie you put on you cinematic bucket list – make it this one.

Got a story?

If you’ve got a celebrity story, video or pictures get in touch with the Metro.co.uk entertainment team by emailing us celebtips@metro.co.uk, calling 020 3615 2145 or by visiting our Submit Stuff page – we’d love to hear from you.

MORE: Chilling images show how 9 major cities could be submerged by water by 2100

MORE: Angela Rayner’s aggressiveness left Grenfell survivors like me appalled

MORE: I slept with 2 guys in 24 hours – how I felt after shocked me