No one, including Warner Bros, was prepared for how successful “The Matrix” would be when it hit theaters on March 31, 1999. Only the second film by the Wachowski siblings (their first being the low-budget indie “Bound”), it would go on the be the fourth highest grossing film of the year, and a cultural phenomenon that became part of our lexicon (“take the red pill,” “plugging into the Matrix”).

The movie’s success would also mark a number of shifts happening in the industry. The diverse approach to casting by the Wachowskis, and their casting directors Mali Finn and Shauna Wolifson, took in building their ensemble helped redefine who could be an American action star, as Hollywood was desperate to move away from its already stale reliance on brawny white males, whose bulging muscles justified their physical prowess. The Wachowskis’ philosophy-inspired script helped usher in an era of narrative gravity and complexity in how studios approached the world-building storytelling of studio IP. And twenty years after release, costume designer Kym Barrett’s vision of what people would wear in 2199 was proving to have a lasting effect on the fashion of 2019.

More from IndieWire

The success of something different, set against the increasingly sagging performance of repeated formulas, will always serve as a marker of inevitable change in Hollywood. In this way “The Matrix” is no different than how people will write about the success of “Barbie” and decline of the MCU in 2023. But “The Matrix” also marked a significant and dramatic change in how films got made in Hollywood, as the craft of choreographing action, post-production sound design, and visual effects would be forever altered.

‘I’m Going To Learn Jiu-jitsu’

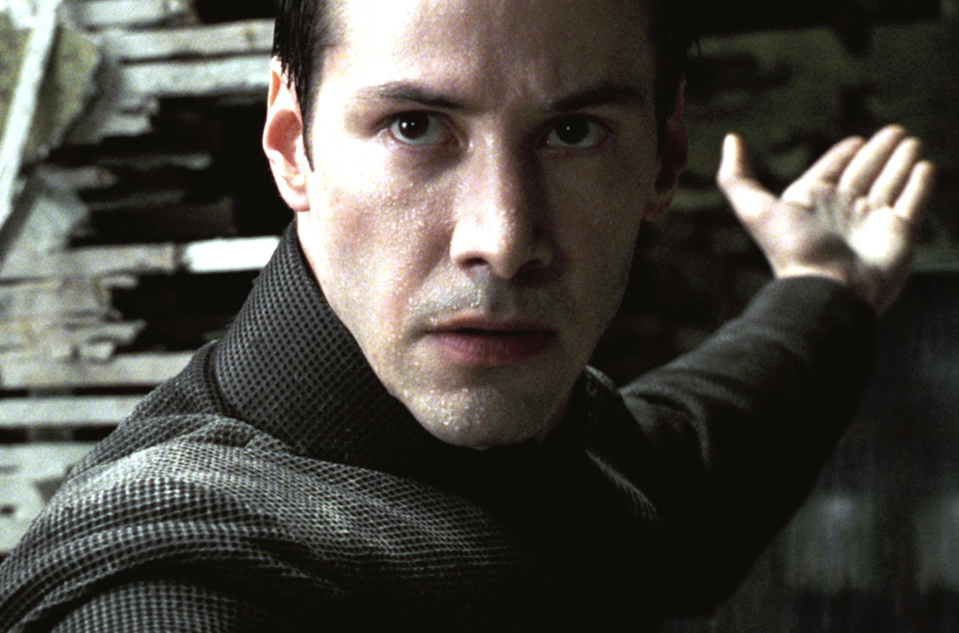

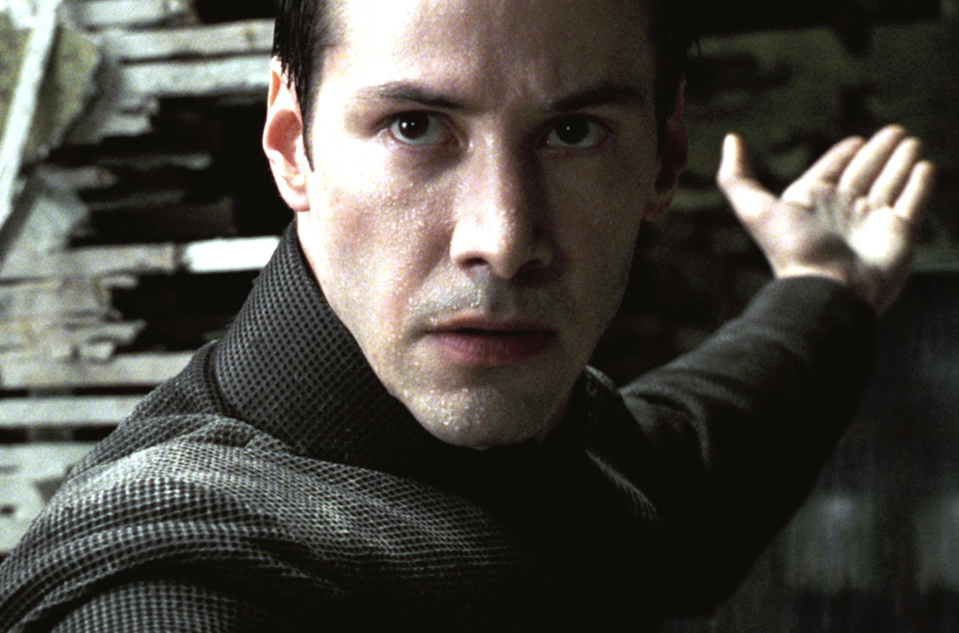

In the late ‘90s, the Wachowskis were not alone in their admiration of Hong Kong martial arts films. From the “wire fu” work in modern Wuxia films, to the “gun fu” of director John Woo, to the incredible practical stunt work by Jackie Chan (which owed a debt to the choreography of the American musical and physical character development of silent clowns), to just the exciting editing, pacing, and camera work of a masterpiece like “Peking Opera Blues,” popular Asian cinema in the 1980s and ’90 is where it was at for cinema enthusiasts. Wanting to incorporate many of these techniques and fight choreography into their action film, the Wachowski’s had baked into their script a perfect narrative device: the Matrix itself. Neo (Keanu Reeves) could be plugged into the matrix, download a training simulation program into his brain, and bam, he knows Jiu-jitsu.

The lasting influence on “The Matrix” though isn’t that the Wachowskis found a narrative justification to sneak martial arts choreography into their film, it’s that they executed it so well. Students of the art form, they brought in top collaborators, principal among them Yuen Woo-ping, the master martial arts choreographer and film director whose collaborations with Chan, Jet li, and director Tsui Hark, among others, had been foundational to the cinematic art form. Together they incorporated the wire-work techniques rooted in Asian cinema into their distinct world, putting their own stamp on must-see action scenes.

“John Wick” director Chad Stahelski, who was Reeves’ stunt double on the first Matrix film, told IndieWire “We talk about it all the time, ‘The Matrix’ was our film school, we all studied at the feet of the Wachowskis.” Stahelski would go onto rise through the ranks as to top stunt coordinator, and then director, while starting the influential 87Eleven action design shop, which continues to carry on the traditions, training, and disciple that stemmed from “The Matrix.” What’s fascinating about the work Stahelski, his former partner David Leitch (“Atomic Blonde,” “The Fall Guy”), and so many others in Hollywood that stormed through the door the Wachowskis opened, is how they continue to blend martial arts styles, mix-and-matching different schools of combat training into their American films, but without the narrative justification of the matrix. In a sense, “The Matrix” changed the audience and opened the fight choreography palette — in a cinematic world of action movies, where humans did the physically impossible, Hollywood stopped worrying about incorporating awkward exposition as to why characters knew Jiu-jitsu. In a sense, we were like Neo, still plugged into the matrix every time we entered the theater.

A Digital Matrix

When sound designer Dane Davis first stepped into “The Matrix” in the late 1990s, he decided to do something radical: It would be the first Hollywood production to work in a purely digital postproduction environment. 25 years later, there isn’t a Hollywood sound department not working the way Davis did on the first film. But unlike today, what was so gutsy is Davis didn’t have the hardware, software, and computing power that makes digital post-production sound work so ubiquitous.

“For me the challenge was finding programs that could produce an aesthetically beautiful texture and feeling,” said Davis. “And still suggest that quantized numerical universe that was the reality as perceived by humans that had evolved and grown up in an analog world.”

Much like the incorporation of Hong Kong action was justified by the concept of the matrix itself, so was the justification of its ground-breaking sound work. Neo and crew were literally entering a digital world of ones and zeros, and a digitally produced soundscape made sense, and justified leaning into the natural artifacting that was inherit to early digital sound production.

As with so much of “The Matrix,” Davis’ innovations in creating the film’s reality-bending soundscape would soon become standard Hollywood practice. But that didn’t stop the Wachowskis and their long-time collaborators from constantly evolving and pushing the filmmaking envelope in the sequels, as Davis and his fellow “Matrix Resurrections” supervising sound editor Stephanie Flack discussed on on IndieWire’s Filmmaker Toolkit podcast.

CGI Landmark & Bullet-time

CGI visual effects were already on the rise and vastly improving prior to “The Matrix,” and the Wachowskis incredible collaboration with visual effects supervisor John Gaeta, and the innovative ways they incorporated CGI into their action sequences and world-building gave CGI a huge boost just by demonstrating what was possible.

The actual innovations were both small and big. The work ESC did in creating virtual human characters, the agents, was ground-breaking at the time, in particular the face swaps and clothing design of Smith, and his fellow agents. But it was the special bullet-time camera rig that was created that really made the biggest impact.

Again, justified narratively by the matrix itself, bullet time created the sense of traveling through space as time stood still, capturing the subjective perspective of how Neo, “the One,” could dodge bullets and do the previously impossible of standing up to the machines and living to tell about it. From film schools to Hollywood blockbusters, bullet-time became so readily copied it became a parody. Watch below, to see how the game-changing effect was first executed.

Best of IndieWire

Sign up for Indiewire’s Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.