A huge chunk of the budget for Chris Hemsworth’s latest box office flop was picked up by Australian taxpayers, it can be revealed.

Precisely how much public money went towards the latest instalment in the Mad Max franchise is unclear, because the figures are kept secret by Screen New South Wales and Screen Australia.

But experts put the bill in the vicinity of at least $183 million – all for the privilege of having the George Miller-directed action film shot on Australian soil.

“It’s incredibly expensive and what value the Australian public get for that cost is questionable,” Professor Kevin Sanson, head of the School of Communication at Queensland University of Technology, told news.com.au.

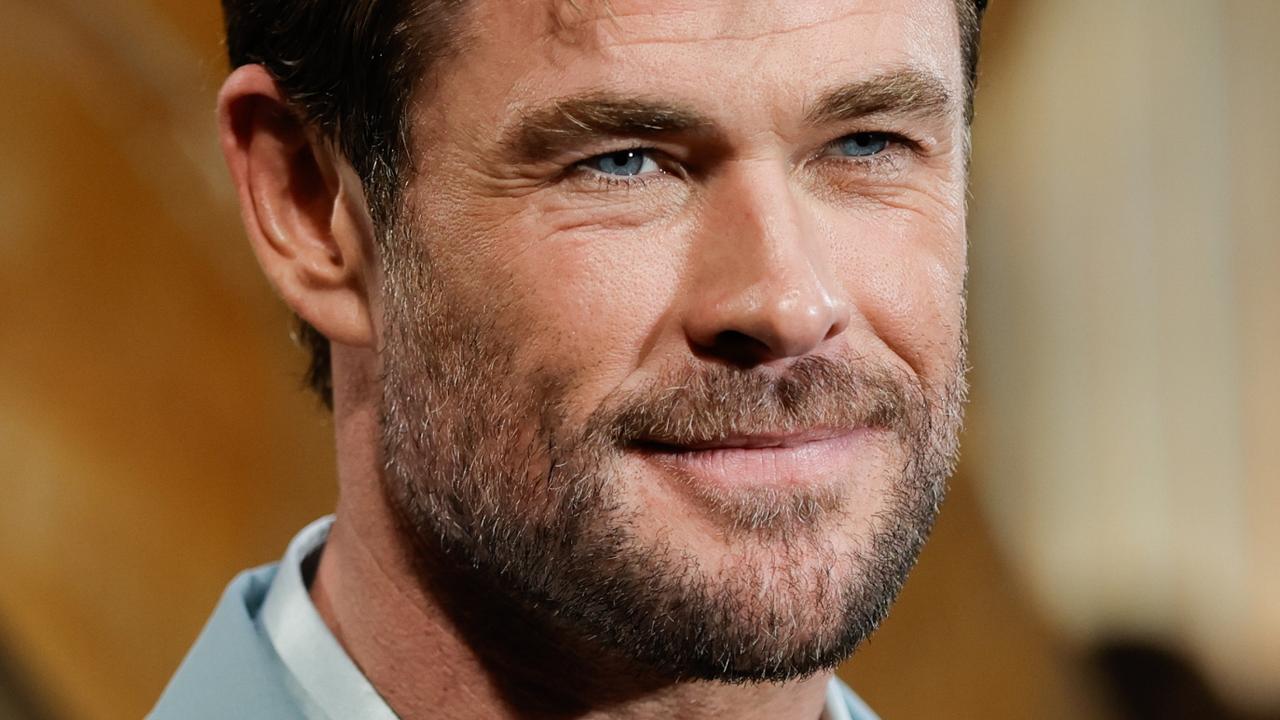

Furiosa’s box office performance has been underwhelming. Picture: Getty

The contribution from the government received by movie powerhouse Warner Bros compromised more than half of Furiosa’s total $333 million budget, it can be revealed.

The NSW Government is estimated to have forked out $50 million, while Screen Australia is tipped to have spent about $133 million.

Despite its star billing and a mammoth marketing campaign, the film’s box office performance has been underwhelming.

Furiosa has brought in just US$160 million (AU$240 million) globally since its release four weeks ago.

“Taxpayers should absolutely question the money spent, not just on this particular production, but the value returned from generous offsets more broadly,” Professor Sanson said.

The first look at the much anticipated new film in the Mad Max series.

But whether the film was popular, critically favoured or even any good doesn’t matter, Professor Sanson’s colleague and research collaborator Amanda Lotz argued.

Professor Lotz, who heads the Transforming Media Industries research program at QUT and authored the book ‘Netflix and Streaming Video: The Business of Subscriber-funded Video on Demand’, penned a damning op-ed about Furiosa, the most expensive movie ever made here.

“The more pressing question is whether its making was a good use of taxpayer money,” Professor Lotz wrote for Nikkei Asia.

“This is an urgent question as the Australian parliament is due to consider an expansion of tax rebates for movies and video series produced domestically.”

Chris Hemsworth in a scene from Furiosa: A Mad Max Saga. Picture: Warner Bros

Anya Taylor-Joy in a scene from Furiosa: A Mad Max Saga. Picture: Warner Bros

Governments provide enticing tax rebates and offsets for international films for two reasons, she explained: to support the development of Australia’s film industry and provide cultural benefits to Australians, and to drive economic benefits.

Iconic local films like Muriel’s Wedding and Priscilla, Queen of the Desert ticked the first box in a big and memorable way, while The Matrix well-and-truly checked off the second.

In more recent years, the criteria has become somewhat overlooked in both respects, Professor Sanson argued.

A location offset, luring foreign productions here, has “no significant Australian cultural test”, meaning there’s no guarantee taxpayer funds “actually return anything of value or interest”.

Back in 2019, the government allocated $540 million for location offsets, which was meant to last until 2027.

“It was completely spent by 2023,” Professor Sanson revealed.

Anya Taylor-Joy and Australian director and screenwriter George Miller at the Cannes Film Festival. Picture: AFP

Now, debate is underway about whether the government should approve unlimited 30 per cent rebates for future productions filmed in the country, regardless of whether they hire Australian talent or tell Australian stories.

“Changing it from a capped budget to an uncapped budget, which means that there is no ceiling, could see it become an incredibly expensive subsidy,” Professor Sanson said.

More countries are competing to be seen as a location of choice for Hollywood productions, which has prompted Australia to dangle an even bigger carrot.

“These sorts of subsidies are a global phenomenon,” Professor Sanson said. “I think it’s a legitimate question whether a company like Warner Bros actually needs that kind of subsidy, particularly when you compare it to other sectors, whether that’s education, health or housing.

“I’m not sure if this big movie producers, whether it’s Warner Bros, NBC Universal or Disney, should get a big taxpayer-funded kickback like they do.”

It’s estimated Aussie taxpayers picked up more than half of the tab for Furiosa. Picture: Getty

It should also be of concern that exactly how much money is handed over remains secret because it’s considered commercial-in-confidence, he said.

A spokesperson for Screen NSW said Furiosa delivered more than $400 million to the state’s economy and created at least 1000 jobs across the state.

However, virtually all of those roles were temporary in nature, Professor Sanson pointed out.

“Based on the research that the team has done, I would question some of the quality of that work,” Professor Sanson said.

“Often in situations where jurisdictions are catering to offshore productions, large-scale productions from Hollywood in particular, the local industry essentially transforms into a service industry.

“And it is an opportunity, absolutely, to work at a creative scale, a budget scale that you can’t do in the domestic industry. But often, most of those positions are junior roles reporting to a foreign head of department.

“The opportunities for professional mobility are largely limited when you’re working at this scale. Hollywood is much more likely to bring the key creative and departmental roles with them because they can afford to do so.

“It creates jobs for below-the-line workers largely, crew, technicians, even someone whose job it is to stand at the perimeter of a shoot location and explain to neighbours that they can’t go through.

“For example, that does very little for our screenwriters in Australia. They’re not benefiting from a location offset because that work is being brought in from abroad. We’re really just servicing the technical side of those productions.”

Premier Gladys Berejiklian has celebrated the filming and production of the prequel to the “Mad Max” movie trilogy in New South Wales.

On top of that, when Hollywood comes to town, limited infrastructure here is either snapped up or surges in price, locking out local producers.

Professor Lutz said moves to uncap location offsets would present a huge risk, saying that “without limits, rebate costs could blow out exponentially”.

“Why do politicians support rebates like location offsets? Politicians like getting their picture taken with movie stars,” she wrote.

“Announcements of big productions coming to town attract favourable news coverage. Filmmaking-support agencies and Hollywood lobbyists use rhetoric and self-funded reports that claim economic benefits from local filming.

“Rigorous and truly independent research is needed to determine whether propping up the global screen sector really provides the best return on investment for taxpayers, or whether spending more on community infrastructure such as hospitals and schools, or live performance spaces and opportunities that nurture emerging artists might be better public investments.

“Lobby groups and filmmaking-support agencies will say that Australia cannot compete without an uncapped rebate. Or that most of the professionally made screen content that circulates widely around the globe was made with rebates.

“The question is, why? ‘Because everyone else is doing it’ has never been a good justification. Maybe it is time taxpayers everywhere stopped footing the bill for global media conglomerates.”

Serious star power wasn’t enough to secure box office success for Furiosa. Picture: Getty

In a statement, Screen NSW said: “Established in 2020, the Made in NSW fund is a five-year program with an original budget allocation of $175 million, designed to support the advancement of NSW as a destination for international and local feature films and major television drama programs.

“Since 2020, the funding has leveraged approximately $1.78 billion in production expenditure in NSW and created over 25,000 jobs in the state.

“It has attracted major international productions including Anyone But You, The Fall Guy and The Kingdom of the Planet of The Apes, and Australian productions including The Artful Dodger, Furiosa: A Mad Max Saga, The Lost Flowers of Alice Hart and the upcoming The Narrow Road to the Deep North to NSW, cementing NSW as the premier filmmaking destination in Australia.”

Meanwhile, a spokesperson for Screen Australia said: “Due to the tax secrecy provisions in the Taxation Administration Act, we are not allowed to disclose which titles receive the [producer] offset as it would identify the tax affairs of the recipient.

“The only publicly available information regarding the offset is the number and aggregate value of certificates issued which are outlined in our annual report.

“In 2022/23 Producer Offset Final Certificates were issued to 214 projects, worth a total of $295.16 million. Some productions that receive the offset do choose to publicly acknowledge they have received it including sometimes including an end credit in the film.”