There is nothing quite like becoming birdpilled. I am not a halfway kind of person: When I got into movies, I turned thinking about movies into my job. When I got into running, it wasn’t long until I was running a half-marathon every weekend. So I know what it’s like to become obsessed—and to start seeing your new obsession everywhere.

But during lockdown, I, like a lot of people, gradually became obsessed with birds—and it turns out that, with birds, they really are everywhere. They’re fluttering outside your window when you’re supposed to be working. They’re singing nearby when you’re supposed to be sleeping. They’re soaring overhead when you’re supposed to be paying attention to oncoming traffic.

Bird-watching does sometimes involve just that—watching birds—but for the truly birdpilled, it’s about tuning in to a new layer of reality around you and decoding it. The word bird becomes not just a noun but a verb, and you are always birding. That bird singing when you’re trying to sleep in, that sounds like a dial-up modem? That’s a song sparrow. That bird fluttering outside your window when you’re supposed to be working? Damn, you think, is that a yellow-rumped warbler? That raptor soaring over your head when you’re supposed to be paying attention to oncoming traffic? Usually it’s a red-tailed hawk, but sometimes it’s a turkey vulture, or a black vulture, or something more interesting, something that maybe merits glancing up just a little while longer …

This is your new reality, and after a few months or years of adjusting to the shock of it, you start to feel as if you’re in the Matrix. In every glimpse of an outer tail feather, every snippet of song, you can see those cascading green lines of code, and after a while, you can read them.

Most of the time, this is a peaceful, meditative activity, the kind that puts you in a flow state and has been scientifically proven to reduce stress. No matter how out of control everything else feels, when you’re out in nature, everything is in its right place.

Still, every once in a while, there’s a glitch in the Matrix. In real life, these oddities are thrilling: If something is out of place, it could be a “vagrant,” a migrating bird that has wandered off course from another side of the country or even another hemisphere.

There are, unfortunately, other types of glitches. They come fast and furious, scrambling your brain. You’re watching Indiana Jones trudge through the jungles of South America in the opening scene of Raiders of the Lost Ark, and one of the first sounds you hear is the famous “awebo” call of the tundra-loving willow ptarmigan, on the wrong end of the American continent. You’re watching Season 3 of The White Lotus, set in Thailand, and you find yourself distracted by the persistent “kon-ka-reeee” of red-winged blackbirds, on the wrong side of the Pacific Ocean. You’re lost in Dune’s sweeping vistas, watching Paul Atreides sulk about his home planet of Caladan, until there it is, on the wrong side of the galaxy: a killdeer.

Like any generous viewer—I consider myself one—you learn to suspend your disbelief. The same way you learn to accept that every phone number in every movie starts with 555, if you’re a birder, you learn to accept that every bald eagle in every movie screeches like a red-tailed hawk.

I maintained this policy throughout my early birdpilling. But then I watched the original movie adaptation of Charlie’s Angels, and I found myself staring down one of the greatest mysteries of recent cinema.

You see, there’s a scene in that movie that tormented me, that kept me up at night, and that lately has had me interrogating a wide variety of seemingly devoted, and certainly well-compensated, filmmaking professionals. That’s because the bird in Charlie’s Angels is, I believe, the wrongest bird in the history of cinema—and one of the weirdest and most inexplicable flubs in any movie I can remember. It is elaborately, even ornately wrong. It has haunted not just me but, as I’d later learn, the birding community at large for almost a quarter of a century.

So, naturally, being an all-in sort of person, I embarked upon a wild-goose chase to investigate how and why this monstrosity took flight. I talked to script doctors and scoured legal statutes. I interviewed leading ornithological experts and electronically analyzed birdcalls, all to figure out who laid this giant egg. It took nearly a year. But eventually, I discovered why hundreds of people with a budget of nearly $100 million failed to accurately portray a single bird. The answer was most fowl.

This story was adapted from an episode of Slate’s podcast Decoder Ring. That episode was written by Forrest Wickman and edited by Willa Paskin and Evan Chung. It was produced by Max Freedman. Listen to the original version:

1. Preproduction

Charlie’s Angels started as a hit 1970s TV show about a trio of crime-fighting women. In 2000 it was adapted into a movie, helmed by the music-video director known as McG. It stars Cameron Diaz, Drew Barrymore, and Lucy Liu, who play three private investigators trying to save the world from (what else?) an evil tech billionaire.

The scene that really drives me cuckoo, the one that aggressively flouts all avian logic, happens right before the big action finale. At this point, the Angels seem done for. Their headquarters has just been blown up—and their beloved helper Bosley (Bill Murray) has been kidnapped and trapped in a prison cell God knows where.

But Bosley has a radio transmitter implanted in a tooth, and so as the Angels wade through the flaming wreckage of their old offices, they hear a familiar voice. At first, they have no idea how to find him, but then a clue appears: A bird flies to the window of Bosley’s cell. And at our heroes’ darkest moment, it sings its song.

“It’s a Sitta pygmaea!” observes Cameron Diaz’s Natalie, who is allegedly a bird expert. “A pygmy nuthatch! They only live in one place: Carmel!”

And so, with that one bit of birdsong, and Natalie’s expertise, the Angels are able to locate Bosley in Carmel, California, free him from his prison cell, and save the day.

Like most of the movie, this scene is knowingly dumb and very fun, and yet, as any bird-lover can’t help but notice, it is absolutely riddled with errors.

The problems with the scene are as follows:

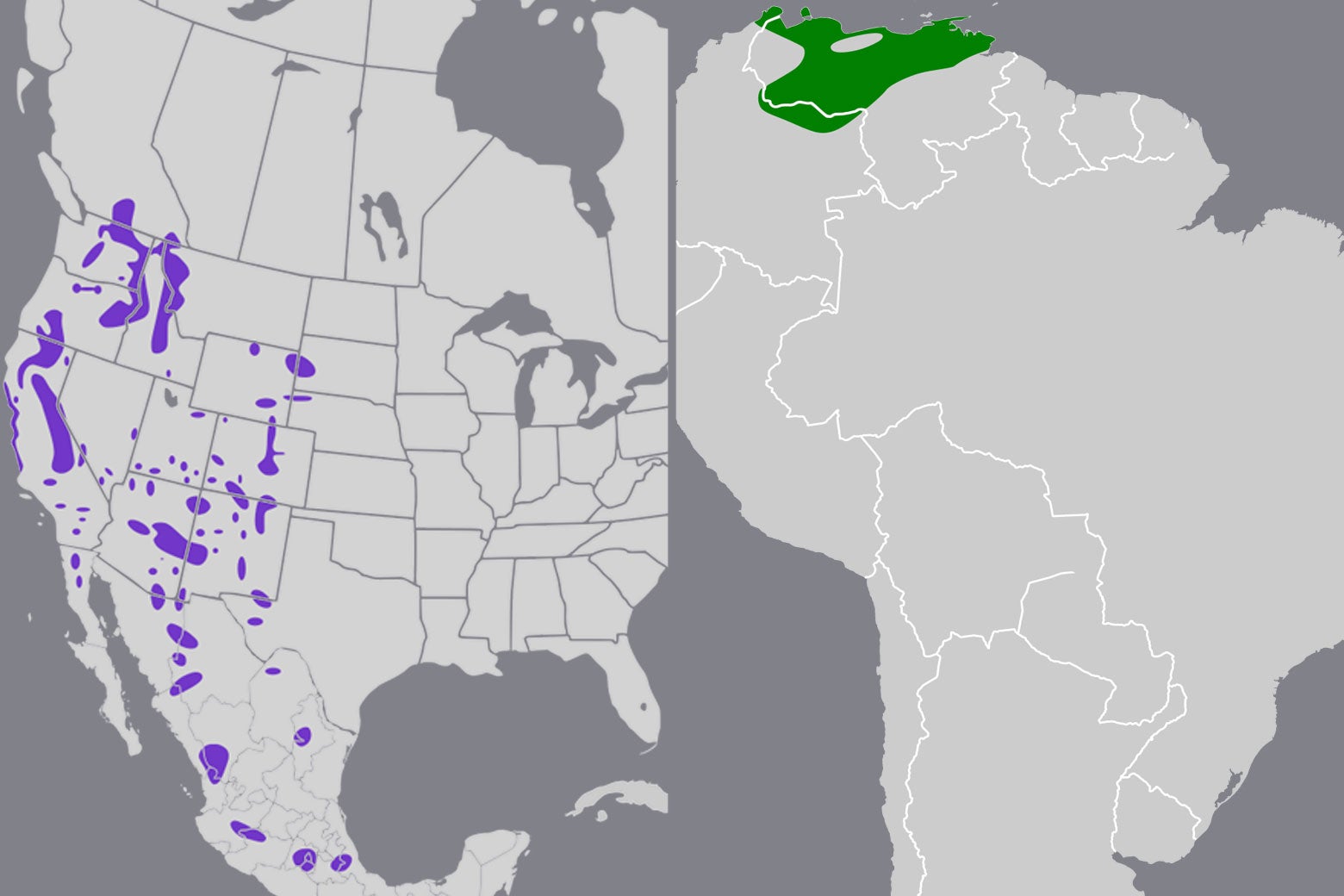

First, the pygmy nuthatch does not “only live in one place.” I’ve personally seen pygmy nuthatches in at least three states, and they can be found in at least three countries.

Second, the bird shown on-screen is not a pygmy nuthatch. The pygmy nuthatch is a tiny, drab, almost gray-scale bird, so small it can fit inside a roll of toilet paper. Instead, what’s on-screen is a Venezuelan troupial, which is black and neon orange, almost six times the size of a pygmy nuthatch, and also—as the name suggests—not found in Carmel.

Finally, and this might be the most baffling thing, the bird heard on the soundtrack is neither a pygmy nuthatch nor a Venezuelan troupial. It’s an unknown third bird whose identity has, until now, befuddled birders for years.

To summarize: The bird in this scene does not live where it’s supposed to, look like it’s supposed to, or sound like it’s supposed to. To put this in terms of mammals, it’s as if a two-toed sloth climbed up to Bill Murray’s window, howled like some unknown species of canine, and Cameron Diaz identified the howl as a sea otter, saying that sea otters live in only one place on Earth: Carmel, California.

Hulton-Deutsch Collection/Corbis/Corbis via Getty Images and Library of Congress

For anyone who knows anything about birds, this scene is a train wreck of the sort that’s simply impossible to ignore. The bird involved is not some background figure: It is not a red-tailed hawk screeching in the distance. It is front and center, strutting around so shamelessly that the first time I saw it, I honestly thought that the filmmakers might be trolling—that they might be flipping me, and others like me, the bird.

I am a journalist, and as such, it was my first responsibility to get the facts. So I decided I needed to methodically make my way through each and every absurd error in this scene to understand how this crime against ornithology had happened.

I was going to start with the very first one: Who introduced a pygmy nuthatch into the script, then had the temerity to say it lived only in Carmel?

From the beginning, it was clear that cracking this mystery was going to be no easy task. “So, when you emailed me,” Charlie’s Angels screenwriter John August told me, when I called him up, back in December 2023, “I had no recollection of a bird being in the movie at all.”

August was hired to write Charlie’s Angels back in 1998, and from the beginning, it was a challenging assignment. “It’s one of the most difficult things I ever had to write,” he said, “because every scene has to do 19 things.” Those things included servicing the storylines of all three Angels, plus Bosley, keeping the complicated plot moving forward, being funny, and keeping every moment action-packed. This was a lot for August to juggle, so it didn’t take long before he copped to not caring about the bird. “I would say, given the many complexities of the Charlie’s Angels script, 100 percent scientific accuracy, bird accuracy, was not a priority.”

Still, he didn’t remember writing the words pygmy nuthatch into the script himself—though he admitted it was possible he had. So I asked August, who keeps meticulous records, if he was willing to show me his very first draft of the script so I could see where it all went wrong.

As he pulled up First Draft A, it began to seem as if his quasi-confession had been premature.

August read aloud from the script: “Bosley whistles to a bright red songbird who has landed on the windowsill. The bird whistles back.” Natalie says, “That’s an ʻiʻiwi. They only live in one place,” and Lucy Liu’s character says, “Hawaii.”

So the pygmy nuthatch was not the bird August had started with. And the bird he had started with? It actually really was 100 percent scientifically accurate. The ‘i‘iwi really is a “bright red songbird” with a whistled song. It really does live in only one place. And that place really is Hawaii.

But for logistical reasons, the location of the scene kept changing. Instead of filming in Hawaii, the team decided to shoot somewhere closer to Hollywood. So the ‘i‘iwi flew out the window, and August had to pick a new bird.

On the draft dated Oct. 26, 1999, the bird was now a “blue-and-white songbird,” August told me. He read aloud again: “Natalie says, ‘That’s a loggerhead shrike: Lanius ludovicianus anthonyi. They only live in one place … Catalina.’ ”

So, already, this wasn’t as on point as the draft with the ‘i‘iwi: A loggerhead shrike isn’t blue. But the Latin name that the script gives belongs to a subspecies, the island loggerhead shrike, which really was known to be only in Catalina—and, OK, a couple of other islands nearby.

“Here’s a little bit of my defense,” August said. “It’s early internet. So I probably had to actually, like, look it up in a book or something about, like, What are birds? and What do birds look like?”

August may not have known a ton about birds, but he had tried to get it right. And yet, at some point, the bird had really jumped the shark. What had gone wrong? Turns out, August left the movie.

“We had a reading, about a month before production started, and that really went disastrously bad,” he said. “People started freaking out about stuff. And at that point, I left the project, and maybe, like, 11 different writers came on and did a week or two of work during production.”

It was actually a whopping 17 writers who ended up working on the script. In the words of a Los Angeles Times article from the time, “Never has so much top-flight talent been put to work on such a trifle.” “There’s what’s called revision pages,” August said. “If you are adding something new to a script, you put those pages out in a different-colored sheet of paper. So first it’s blue revisions, then pink revisions and yellow revisions. They went through that color rainbow so many times it was like double-cherry revisions by the time the movie stopped shooting.”

So whenever our pygmy nuthatch entered the script, it must have been on one of those colored revision pages, written by one of the other 16 screenwriters who worked on this movie. That meant that there were 16 other suspects to question, and any one of them could have written in the pygmy nuthatch.

I started with Zak Penn. Penn has worked on some of the biggest action franchises of the past three decades, including the X-Men and Avengers movies. But I had tracked him down because I had reason to believe that his rewrites had touched on the bird.

His name was on a later draft of the script I found online, in which the bird had been changed to something even worse: a “blue-spotted egret,” which isn’t a real bird at all. I figured that anyone who had the nerve to straight-up invent a species could have also been the wrongdoer behind our pygmy nuthatch.

“You know, when I was a kid, I actually had, like, a bird-watching book. I remember, like, black-capped chickadees, things like that,” Penn told me when I reached him. Had I underestimated him? But then: “Until you told me a blue-spotted egret wasn’t a real bird, I had no idea that it wasn’t,” he confessed. “I couldn’t give less of a shit about birds.”

Despite his rather cavalier attitude toward some of our world’s most beautiful creatures, Penn denied responsibility for the bogus blue-spotted egret. He also didn’t think he had come up with the pygmy nuthatch, and he didn’t know who had.

But just as I began to mentally prepare to cross-examine the other 15 screenwriters, Penn pulled me back from the brink. He told me that even though he didn’t know the identity of the guilty party, he was pretty sure he knew their motive. “Charlie’s Angels was pretty betwixt and between, and therefore that leads to a lot of people throwing a lot of shit at the screen, trying to find something that sticks,” he explained. “It’s so hard writing a comedy in the studio system, because everybody gets bored and thinks the script isn’t funny anymore because this is the 18th draft they’ve read.” While Penn and I could hatch conspiracy theories, he told me, “my guess is, it’s the chaos is what led to this.” All those writers were desperate for a bird that could make their bosses laugh—and could keep them laughing on the 18th read.

And Penn thinks the pygmy nuthatch’s name makes it uniquely qualified in that regard. “If somebody had said, ‘You know what bird? You’re talking a pygmy nuthatch,’ I would be like, ‘That’s fucking good. Let’s use pygmy nuthatch.’ ”

August agreed. “I suspect that one of the writers who was on board for a week, and just doing kind of surface-level changes, picked a funnier word.” After all, he pointed out, “it has the word nut in it.”

Perhaps chaos and comedy were the true culprits: So out had gone the accurate ‘i‘iwi, the semi-accurate shrike, even the godforsaken “blue-spotted egret”—and in came the pygmy nuthatch.

But for the life of me, I still could not understand: Why didn’t they then use that bird in the movie? If you put it in the script that Bill Murray’s scene partner is a pygmy nuthatch, why not cast a pygmy nuthatch? It was time for me to find out who was responsible, by finding a witness to the film shoot and getting them to sing like a canary.

2. Production

So the screenwriters had in all likelihood introduced the name pygmy nuthatch to be funny, but then someone had to go get an actual bird.

“There’s a lot of species of birds you just wouldn’t ever want to use,” Guin Dill, who’s been wrangling animals for 30 years, told me. “They just can’t handle it. If a bird gets stressed, they go poof. And they just, like … lose all their feathers. And then what do you do?”

Dill was the animal trainer on Charlie’s Angels. As such, she was responsible for finding the pygmy nuthatch specified in the screenplay and putting it in front of a camera. But as you know, the bird on-screen is decidedly not a pygmy nuthatch. Was she to blame?

“That wasn’t our decision,” Dill said. The humble gray pygmy nuthatch did not have the look the producers and director were going for. “They wanted something very tropical because it was supposed to give it away that he’s on this island. So, keeping that in mind, they were kind of looking for vibrant, a little bit spectacular.” But not too spectacular: “It had to be a small enough bird to fly in through the window, do the song, and then fly out.”

So Dill had to find birds that would fit the bill and share them with the production team. “We sent pictures, initially. It’s kind of like sending headshots of actors. We do the same thing, so we send them an array of pictures, and then they kind of pick and choose, whether it be because of their ability or look.”

Now, if I were an animal casting director, I would have included at least a headshot of the pygmy nuthatch. It might not be the flashiest performer, but why not give authenticity a chance?

Or that’s what I thought, until I learned something unexpected. “We cannot use a lot of birds that are indigenous to the United States,” Dill said. “So it’s really difficult. It’s not that easy.”

It turns out no animal handler would ever have included a pygmy nuthatch, not just because they are small, colorless, and unlikely to grab a viewer’s eye. They are also illegal to cast in a movie.

The reason for this goes back more than 100 years.

“People in the late 19th century and early 20th century were just killing birds wholesale,” Nick Lund told me. Lund works for Maine Audubon, and for more than a decade, he has written countless articles—for the Washington Post, Slate, and Audubon magazine—about the ways that Hollywood gets birds wrong. “There were not the same rules that there are now about hunting regulations, hunting season, bag limits, that kind of thing. And birds were just getting decimated.”

Some of this was for food, but people were eating much more than turkeys and pheasants and ducks. They were eating sparrows, grebes, loons, thrushes, grackles, ibis, pelicans, bobolinks, woodpeckers, and more. If you can think of a bird, it was probably on the menu. In one of John James Audubon’s books, he reported that the snowy owl (aka Hedwig from Harry Potter) tastes like chicken.

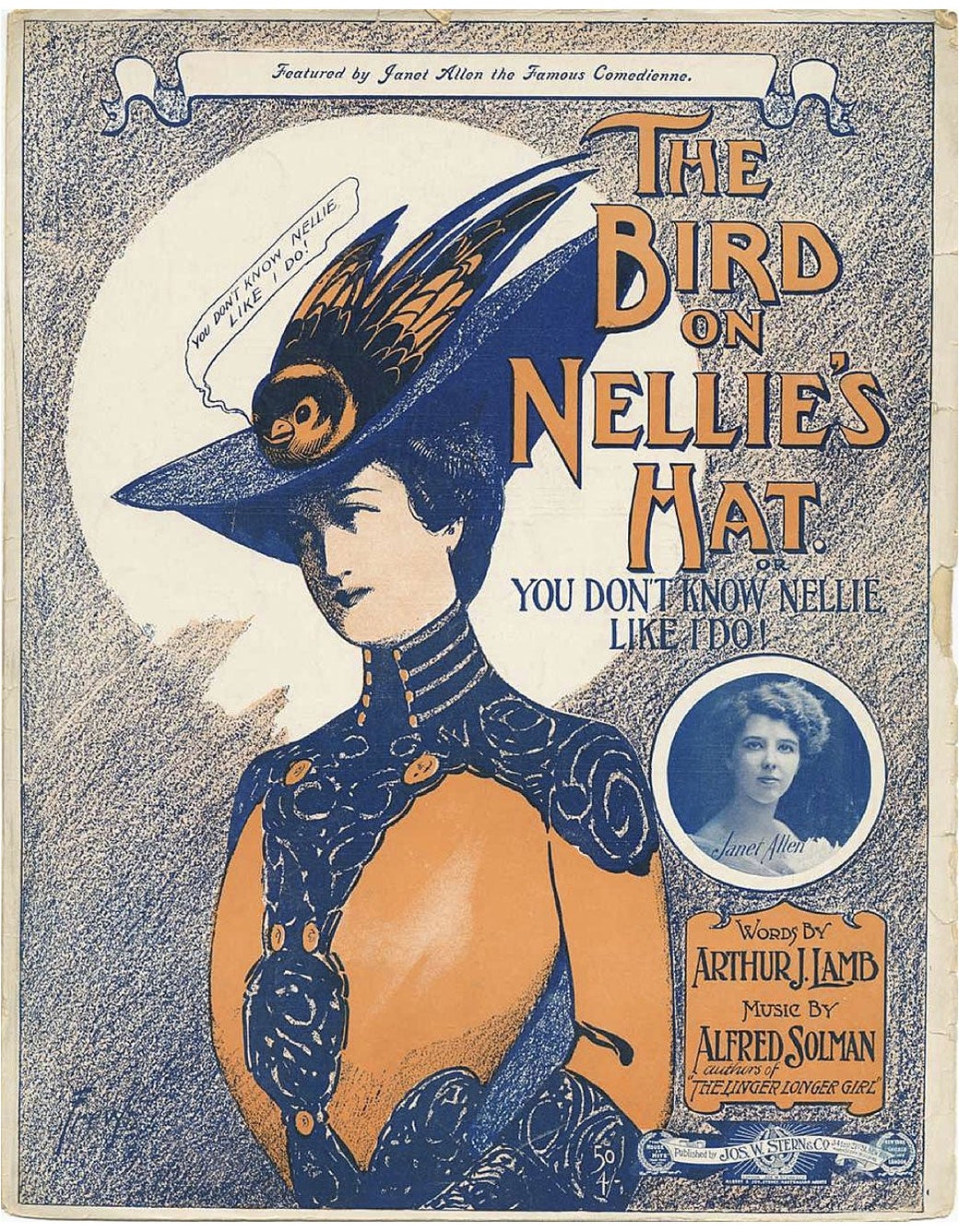

And birds were being killed not only for sport and sustenance. They were being killed for women’s hats. “There was this giant millinery trade. And so people were killing birds for their feathers to make these dumb-looking hats that were super popular at the time.” Often, Americans were slaughtering whole rookeries full of egrets for their snow-white plumes. Other times, they were taking “Put a Bird on It” to new extremes, taking an entire dead bird and just plopping it onto a hat. It was like if you took Björk’s infamous swan dress and put it on her head—and made it out of an actual swan.

In February 1886, at the height of the fashion craze, ornithologist Frank Chapman went birding through Manhattan, simply counting the birds on women’s hats. Over two afternoons, he tallied more than 500 hats adorned with more than 40 species of birds, including blue jays, bluebirds, red-headed woodpeckers, Baltimore orioles, common terns, a prairie hen, and a saw-whet owl.

At first, Americans weren’t too concerned about what all this carnage meant for bird populations. In the 1800s, scientists were still debating whether it was even possible for a species to go extinct. Audubon himself insisted that North American birds were so numerous that, at least with our birds, it could never happen.

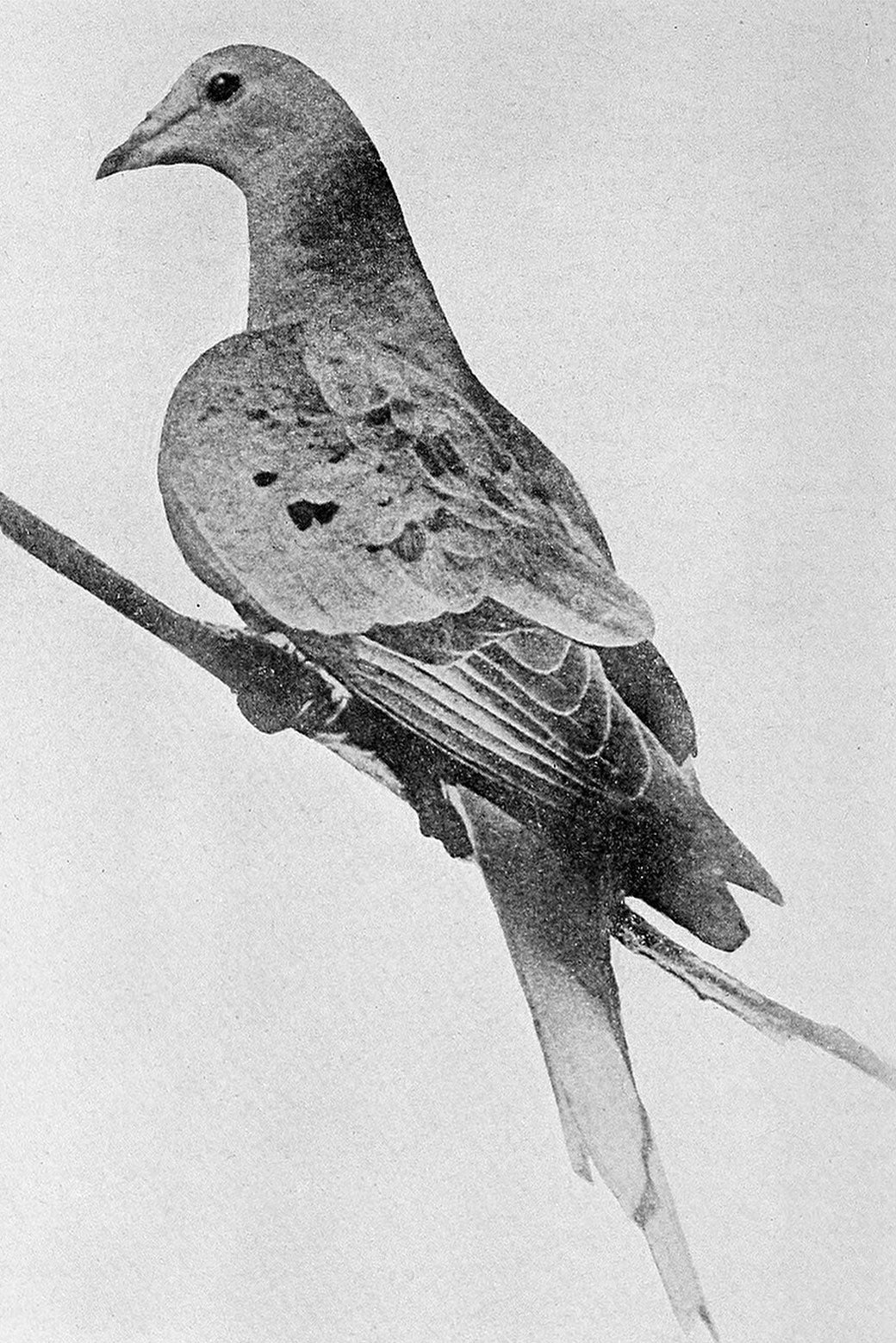

And then came the tragic case of the passenger pigeon. The passenger pigeon had once been so plentiful across North America that Audubon described them blotting out the sun for days. But they were massacred by the thousands, and in 1914, a passenger pigeon named Martha, the last known member of her species, died alone at the Cincinnati Zoo.

Enno Meyer/Archives/Wikipedia

There was powerful outrage about all of this bloodshed—but especially about the hats. The hats were worn mostly by women, and the fight against the hats was also led largely by women. Two of those women were Harriet Hemenway and Minna B. Hall, who, 10 years after Chapman’s expedition through the fashion district, founded the first Audubon Society.

“It actually makes me laugh because, you know, it’s such a dumb fashion trend, and it resulted in all these great laws,” Lund told me.

One of these laws is the Migratory Bird Treaty Act. It was passed in 1918. “It’s this interesting, wide-ranging, broad law that protects migratory birds,” Lund said. “It basically prevents people from harming, taking, killing, capturing native birds in the United States.”

The law has had humongous positive impacts. It’s been credited with saving everything from the snowy egret to the wood duck and the sandhill crane.

But the law also says that you can’t keep our native birds as pets. And though we may not be used to thinking of animals in movies as pets, that’s what they are: working pets. “And so when a company wants to put a bird on TV in the United States,” Lund explained, “they can’t use a native species.”

And a pygmy nuthatch is a native species, a bird covered by the Migratory Bird Treaty Act.

So even if anyone involved in Charlie’s Angels had wanted to use a lowly pygmy nuthatch in the movie, they couldn’t have. They were always going to have to use another bird. And once that’s true, I mean, why not get a bird that has real star quality?

And so that’s exactly what Guin Dill, the animal handler, did. In fact, she got two of them.

“Jack and Jill,” she told me. “They were brother and sister.” In a bit of a Mary-Kate and Ashley Olsen scenario, both of them appear in the movie.

Jack and Jill might not have been great at taking direction—they would peck at Dill’s cuticles; she thinks she still has scars from them today—but as Venezuelan troupials, they were resplendent birds the color of a tangerine, with shiny black hoods, a sky-blue teardrop around each eye, and a blazing lightning bolt across each wing. The camera loved them.

So now I knew why screenwriters would write in a pygmy nuthatch and why, to cast one, an animal handler had to bring in a foreign import. Still, even once the filmmakers were stuck with the name they picked for fun, and the South American stand-ins that they were legally allowed to put in the movie, they still could have … made their bird sound like an actual pygmy nuthatch, right? Or even like a Venezuelan troupial? But in fact, they did neither: They cast a third bird to lend its voice, one that nobody has been able to identify.

And that means there were actually two mysteries left: Why on Earth did they do that—and what bird was it?

3. Postproduction

I had been wondering what the hell voices the pygmy nuthatch since the moment I first saw Charlie’s Angels. And it wasn’t just me. For decades, birders have been flocking to the internet to point out the problems with this scene: blogging about it, tweeting about it, posting it to forums and message boards and IMDb Goofs and moviemistakes.com, publishing it everywhere from local newspapers to books to W magazine.

But while these enraged ornithophiles have long identified the “Hollywood impostor” on-screen as the national bird of Venezuela, none of them has ever been able to identify the bird we hear. And with just my ear, I couldn’t either.

Still, I was going to figure this out one way or another. I started by reaching out to the crew member who ought to know best: Michael Benavente, who was the supervising sound editor of Charlie’s Angels, as well as its sequel Charlie’s Angels: Full Throttle.

Benavente told me up front not only that he didn’t remember much about the bird, but that it really wasn’t a priority at the time. “To be honest, that sound was a very minor part of the film,” he said. “I know it was a plot point and pays off and that kind of stuff, but there was so much other stuff going on with sword fights and, you know, big action sequences.”

But I’d come this far, and I wasn’t going to take indifference for an answer. So I asked him to rewatch the scene with me over Zoom, and some things started to click. The first was that, in the context of the scene, an accurate sound effect wouldn’t have felt right: “Quite frankly, realistic doesn’t always play dramatically or as interesting. You want to punch things up and make them sound fun,” he said.

The bird is helping the Angels set Bosley free. It doesn’t need to sound accurate—it needs to sound like deliverance. And for what it’s worth, that is not the song of a Venezuelan troupial, which sounds more like a car alarm.

The song of a real pygmy nuthatch has problems too—namely, it sounds as if it’s being chewed up like a squeaky toy.

“Yeah, a lot of times the real thing just isn’t cutting it,” Benavente said.

So Benavente’s team needed to deliver a birdsong that was more uplifting and joyful. But there was another thing. Not only did they have to match the song to the bird on-screen; they had to match it to one of the humans: Cameron Diaz.

See, if you listen very closely to the sound effect, as I have, there’s a rising, whistled trill at the end that repeats three times. But the third time you hear it, it’s actually Diaz’s character whistling a pitch-perfect imitation of the bird, blowing through her hands as if they’re a flute.

And that’s the thing that Benavente was focused on. “Basically, I would be more concerned about making sure it looked like it was coming out of her mouth,” he said. In other words, he and his team had to find a birdsong whose rhythm could line up with the visuals that had already been filmed.

So now I knew why they hadn’t used the song of a pygmy nuthatch or a Venezuelan troupial. But that’s where I hit a dead end. Benavente had no idea what bird they had used instead.

Still, I was undeterred. Even if I couldn’t identify the bird, I knew who probably could.

Nathan Pieplow is the author of the definitive Peterson Field Guide to Bird Sounds of Eastern and Western North America, which is sort of like Webster’s Dictionary for birdsongs and birdcalls. (He is also an “obsessive birder,” he told me, who is “not allowed by my friends and family to comment on the bird sounds when we are watching movies or TV, because they have had enough of my commentary.”)

One of the reasons Pieplow’s guides are so authoritative is that he helped pioneer a method that relies not on our ears but on our eyes. “The beautiful thing now that you can do is you can create what we call spectrograms, which are computer-generated pictures of the sound,” he said. A spectrogram is a visual representation of an audio recording, and in Pieplow’s field guides, they look like notes on a staff. It’s sheet music for birders.

“With practice,” he explained, “you can learn how to read the spectrograms so that you can look at the picture and you’ll know what it sounds like, or the other way around. If you hear a bird sound, you can picture what it’s going to look like.”

All this practice has made Pieplow an excellent ear birder. While warming him up, I played him birdsongs as far-flung as the pygmy nuthatch and the ‘i‘iwi, and he nailed them all.

But when I played him our mystery bird, even he, the guy who literally wrote the book on North American bird sounds, couldn’t identify it. This bird was really, really, ridiculously hard to pinpoint.

And as I listened to it over and over, I kept circling back to that part that repeats at the end—that Cameron Diaz whistles back perfectly. It’s weird, because it repeats exactly—and I mean exactly—in a way that almost sounds too uncanny, too mechanical, to be the work of any real bird. Was it possible it wasn’t the call of a real bird? Could it be … synthesized by a machine?

There was only one thing to do: ask another machine.

Merlin is an app, downloaded more than 10 million times, that’s basically Shazam for birds. Making “Shazam for birds” had been the holy grail of many birders before, but Merlin, which was developed by the renowned Cornell Lab of Ornithology, really cracked it.

I’d already tried using Merlin on Charlie’s Angels, and the app had been just as bewildered as the rest of us. But I called up Drew Weber, the project manager for Merlin, who explained that the app on my phone would never identify this sound for me—and that’s by design. “By default, Merlin’s only going to show you results for your location and your time of year,” he said.

But then he told me there’s another, more powerful version of the software: “Internally we have what we call the dev app. And it allows us to toggle off the various filtering for location and time of year.”

So Weber set loose his behind-the-scenes version of Merlin on Charlie’s Angels—and he got a hit.

“The song that we were hearing is a fox sparrow,” he said.

I was dumbfounded. We have fox sparrows in New York City! I’ve had them in my literal backyard. If the bird in Charlie’s Angels was a fox sparrow, why hadn’t I been able to identify the song on my own? For that matter, why hadn’t my version of Merlin?

But Weber told me that the fox sparrow in Charlie’s Angels was no New Yorker: “It sounds like the thick-billed subspecies, from California.”

I had to admit: The thick-billed fox sparrow sounded pretty close. But I still wasn’t sure it was quite right—even Weber would admit that Merlin’s A.I. was often wrong—and I wanted a second, human opinion. So I emailed this ID to Pieplow, the birdcall expert.

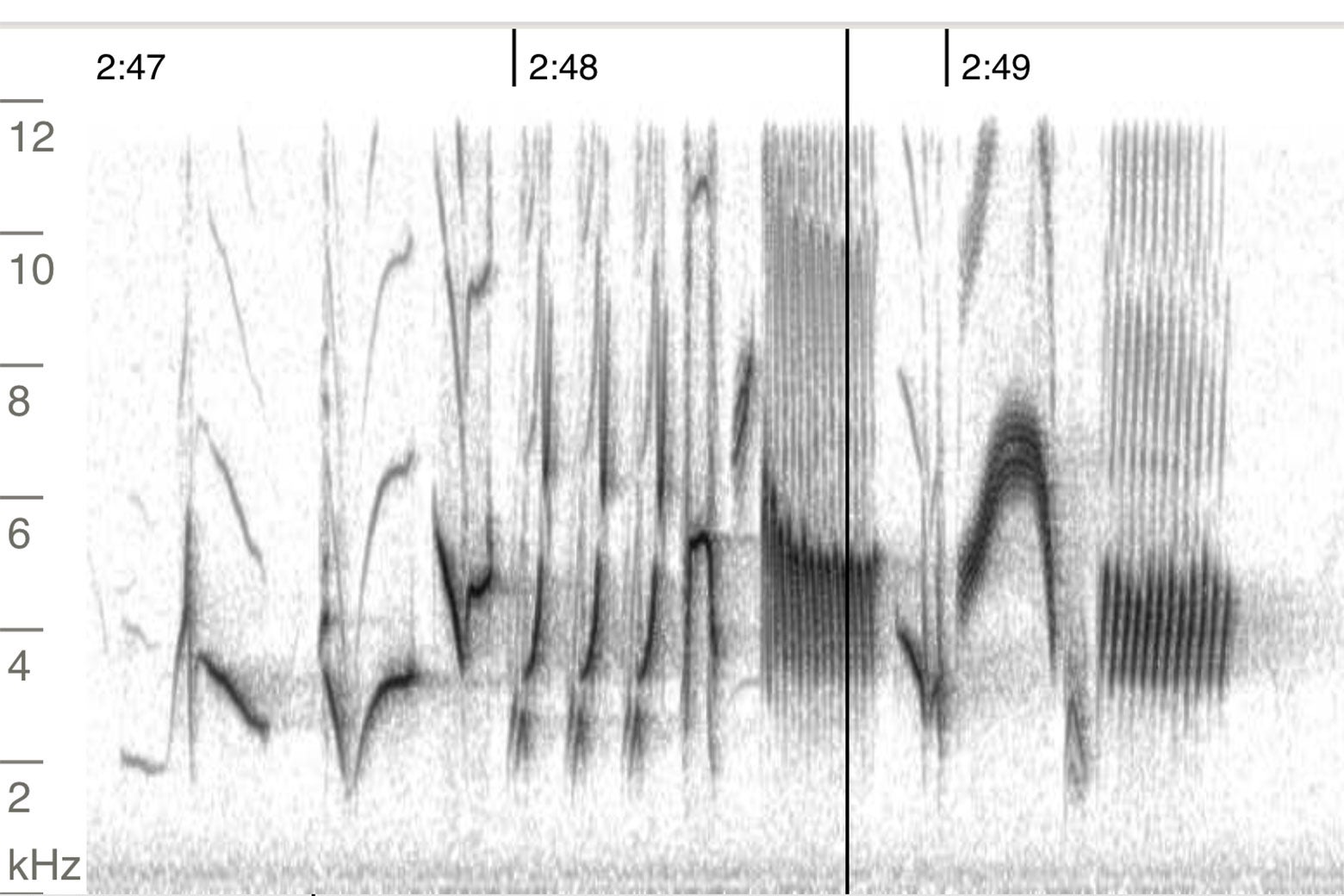

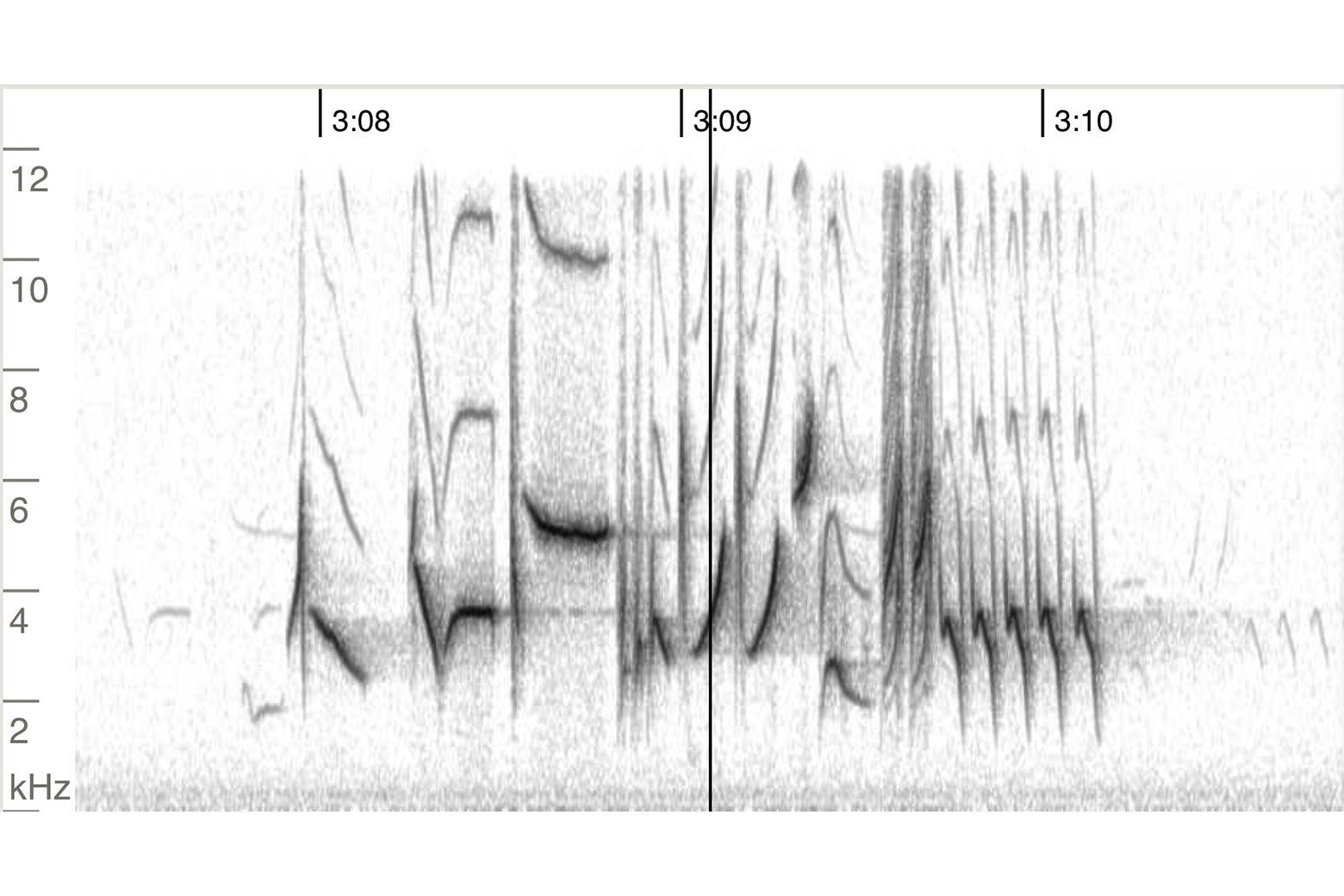

Pieplow wrote back, asking me to give him a call. “I made a spectrogram of the bird that’s singing in Charlie’s Angels,” he told me. “And so I started thinking, Maybe, maybe I could actually find the source recording that this was made from.”

As Pieplow proceeded to explain, when he was researching his field guide to bird sounds, he had fed a vast library of field recordings of birds into a computer program to turn them into spectrograms, spectrograms he still had.

“So I went to the folder called Thick-Billed Fox Sparrow, and within about two minutes I had found the exact individual bird that was recorded and used in Charlie’s Angels,” he said.

I could hardly contain myself. He had found not only the species, not only the subspecies, but the precise individual that was recorded singing nearly 35 years ago: “It is a thick-billed fox sparrow that was recorded by Thomas G. Sander on June 2, 1990, at the Black Pine Spring Campground in the Deschutes National Forest in Oregon.”

Screengrab from the Macaulay Library

It was the smoking gun. I had goose bumps. We had gotten our bird.

And then it got even better. Pieplow explained to me what was going on with that weirdly mechanical series of trills at the end: The recording had been tampered with. The song we hear in the movie is actually stitched together from two different parts of that same 14-minute recording: The movie uses mostly the first couple of seconds of when the bird sings at 2:47, but then it also tacks on the trill that the bird sings only once, at 3:07—looping it three times so that we can hear it twice before Diaz performs it back, in perfect sync.

Screengrab from the Macaulay Library

It was the butterfly effect: An actress flaps her hands on a set in California and, months later, a thick-billed fox sparrow, in an editing room, sings.

4. Release

By this point I was feeling pretty satisfied with all I’d been able to uncover, and it was starting to make me see things a little differently.

I had begun this investigation thinking that everyone involved in this movie just didn’t care about birds, but now I knew that wasn’t the case. I mean, they didn’t really care about birds, but rather than being lazy, or incompetent, or malevolent, they had each been trying to solve a problem—and had stretched themselves to do so creatively. And I could understand and even admire that.

But I couldn’t let it obscure the big picture. The bird in Charlie’s Angels was still a mess. As resourceful as everyone had been, their individual choices did not add up!

And there is one person on a movie who is supposed to keep that from happening—one person who is supposed to be taking in the bird’s-eye view. And so I needed to go to that person and demand an explanation. I needed to talk to the director.

Before Charlie’s Angels, McG was best known for music videos, like the one for “All Star” by Smash Mouth. He’s since gone on to direct the fourth movie in the Terminator franchise and, around the time I interviewed him, the No. 1 movie on Netflix, Uglies. But Charlie’s Angels is what made McG McG—and I was curious if any of this bird drama had even registered with him.

After I got in touch with him, he came out strong. “With the greatest respect, I’m the only person to speak on this issue,” McG told me.

Kevin Winter/Getty Images

It turns out McG remembered everything. He had total recall of the scene, right down to the bird’s Latin name—and he was well aware there was a problem with using that song: “The call is very different of a Sitta pygmaea than the call reflected in the film.”

This was my guy! He got it! And not only had he given a hoot, but he’d tried to make it right.

Before deciding on the two Venezuelan troupials he got from Guin Dill, the animal wrangler, he’d actually wanted to use a bird that looked a lot more like a real pygmy nuthatch. But that bird wouldn’t fly.

It “had a very bright white underbelly,” he explained. “And on top of having difficulty hitting its mark, the white underbelly was casting a bounce onto Bill Murray’s face that was unsavory to the director of photography.”

At this point—it saddens me a little to say—McG, like everyone else, had given up. The movie was over budget, and he was under a lot of pressure. “I was nearly fired off that movie, you know, no less than six or eight times,” he said. “Because it was just so colorful and weird and buoyant and effervescent, and, you know, the studio brass at the time was like, ‘What the fuck is this?’ ”

So he was going to do whatever it took to get the shot. “You can’t spend 90 minutes trying to get the bird to sit on the windowsill to interact with Bill Murray. If one bird can do it, that bird, you know, that bird’s going in.”

And the pygmy nuthatch did have something going for it: its name! It was wrong in all sorts of ways, but the tone, the spirit, the word nut—it had that special something. McG knew it the first time he heard it. “What a great name,” he remembers thinking. “We got to do it. It felt so Charlie’s Angels.”

And McG, he definitely knew what felt like Charlie’s Angels.

Charlie’s Angels, with its goofball mix of action, comedy, and knowing stupidity, became a franchise-launching hit, earning good reviews and one of the highest-grossing opening weekends ever for a first-time director. And—though I hate to admit it—it did it all with a Frankenstein’s monster of a bird.

A bird I had learned was the fault not of any one person—but of many. If this were a whodunit, it would be Murder on the Orient Express, with not just one culprit but dozens, each with their own motive, their own problem to solve. They might be bound by laws. They might be bound by vibes. They might be bound by the small size of the prison window on the set that they already built. And as I’ve learned, you can’t make a movie without breaking some eggs.

“We desperately wanted to get it right,” McG told me. “But then, with great regularity, reality shows up and kicks you in the ass.”

I knew, with this scene, what “right” meant to me—but I am not too stubborn to admit that the people actually working on the film got it right in so many other ways: They picked a bird name that would make you laugh, bird actors who would hit their marks and catch your eye, and a birdsong that would sound like hope.

For years, I thought I had caught the movie out, in this egregious mistake. But maybe I was the birdbrain. Maybe it was time for me to eat crow.

Maybe the wrongest bird in the history of the movies is just right.