No standing ovation at the Cannes or Sundance film festivals could match the unique emotional intensity of one delivered to a filmmaker named B. Raheem Ballard on Thursday afternoon inside a stuffy chapel at San Quentin.

That morning, Ballard, who has been incarcerated for 22 years on charges of robbery and murder, missed the world premiere of a film he directed, Dying Alone, and the follow-up Q&A with comedian W. Kamau Bell, because the event conflicted with his parole board hearing.

“Quick update,” said one of the festival’s two emcees, Juan Moreno Haines, interrupting the afternoon awards ceremony. “Raheem was found suitable.” Ballard, who had been sentenced to be in prison until 2039, had just learned that he would soon be released, and he walked, blinking, into a roaring crowd in the chapel. “I’m overwhelmed,” he said. Moments later, Ballard’s movie won a prize from the International Documentary Association, but he had left to call his family with the day’s news.

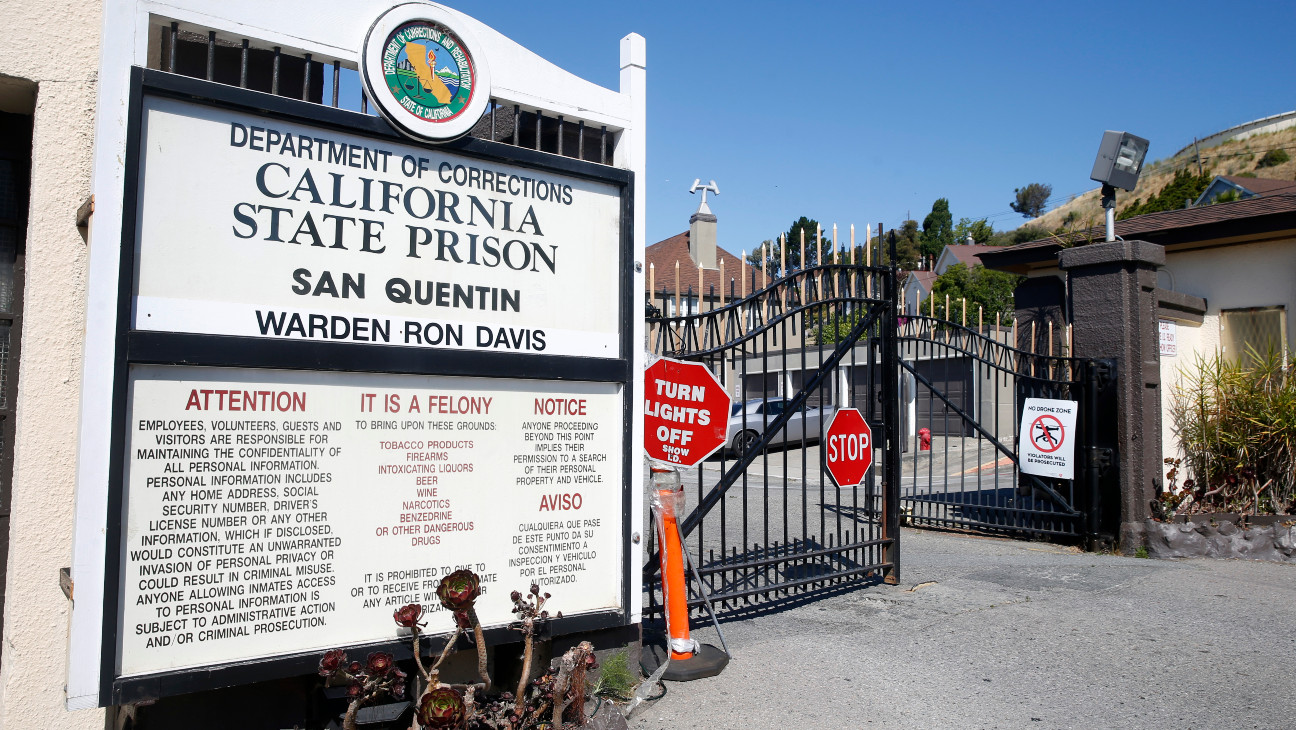

Some 300 people, including American Fiction director Cord Jefferson, Sing Sing director Greg Kwedar, Just Mercy producer Scott Budnick, The Inspection director Elegance Bratton and executive producer of PBS’s POV series, Erika Dilday, were gathered in Chapel B for the San Quentin Film Festival. The first film festival ever held inside a prison, the event took place Oct. 10 and 11 at the San Francisco Bay Area maximum correctional facility and featured screenings of Oscar contenders like A24’s Sing Sing and Netflix’s Daughters alongside films made by current and formerly incarcerated filmmakers. Sitting beside the industry figures in the audience were men, like Ballard, who are currently incarcerated at San Quentin, wearing their blue California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation uniforms.

Just inside the barbed wire fences and under the windows of the building that housed California’s death row until just two months ago, the morning began with a step-and-repeat red carpet in the courtyard, where a prison band played and coffee and pastries were served.

“I’m very anxious,” said Louis Sale, whose 10-minute film, Healing Through Hula, would be premiering that morning. “I’m nervous to see how the story is received.” By the afternoon, Sale, a Hawaiian veteran who is serving 15 years to life, had won best documentary short for the movie he made about an unlikely club that practices hula dancing inside San Quentin. During his comments to the audience, Sale dedicated his film to the Hawaiian culture he had given up at age 14 “because I thought I was too cool” and to the man he had killed while drunk driving in 2016, Vivaldo Veloso.

The event was conceived by Cori Thomas, a playwright and San Quentin volunteer, and Rahsaan “New York” Thomas (no relation), co-host and producer of the award-winning Ear Hustle podcast, who was released from San Quentin in 2023.

Throughout the day, there were signs this was not your typical film festival. San Quentin’s warden, Chance Andres, gave opening remarks in which he praised the “good vibes” as corrections officers in green uniforms looked on. The midday meal was baloney sandwiches and pretzels: “We didn’t fund everything we wanted, so y’all are getting state lunches,” Rahsaan said. The power briefly went out when too many fans were running in the chapel, and no one was allowed to bring a cell phone into the prison, making for a rare 2024 film event where everyone actually appeared to be looking at the same screen in the front of the room. During a filmmaker panel, one of the incarcerated directors asked if there was anyone from the Tracy Morgan TBS show The Last O.G. in the audience —there wasn’t, but he was checking because he didn’t want to offend when he described the show about an ex-con as inauthentic. “Your writers for those types of shows, we’re in here,” he said. “Don’t guess, call me.” In presenting one of the day’s awards, Anthony Gomez, who participates in San Quentin’s film and TV production training program Forward This, declared, “I don’t know about y’all, but today I feel free.”

For members of the Hollywood community in attendance, the event was a refreshing break from the norm. “This is one of the most beautiful days of my entire life,” Jefferson said. Kwedar, who is currently on the awards trail with Sing Sing, said that process “can easily consume your idea of what success is.” But sitting in the chapel at San Quentin, “I feel restored. I just feel more alive.”

During the evening’s screening of Sing Sing, which stars Colman Domingo and Paul Raci alongside a cast of formerly incarcerated men, the audience reacted to key moments and lines, snapping fingers, leaning forward in their seats and saying “that’s right” and “preach” as the movie about an arts program at Sing Sing Maximum Security Prison unfolded.

When the post-screening Q&A was still going on at 7:55pm, Haines paused the proceedings to say, “You know what time it is. Don’t miss count,” a reminder for anyone in the audience who was identified as “close custody,” meaning under a stricter level of supervision, to return to their cells.

“We represent y’all,” Clarence “Divine Eye” Maclin, an actor who served at Sing Sing and plays a version of himself in the film, said at the Q&A. “Thanks for the inspiration.”