As a little girl I had ears that stuck out like big butterfly wings. Some kids at my school in Los Angeles would make fun of them, and I’d often stare at myself in the mirror wishing my ears would lay flat against my head.

But it wasn’t until landing my first major role on a TV show at age 12 that I opted to undergo ear-pinning surgery, a decision I’ve never made public until now. For years, my parents watched me struggle with private shame, though they understood I was a tough kid who could handle it. But once I knew millions of people all over the world would be judging me on their television screens, not just on a playground, that knowledge changed everything for me.

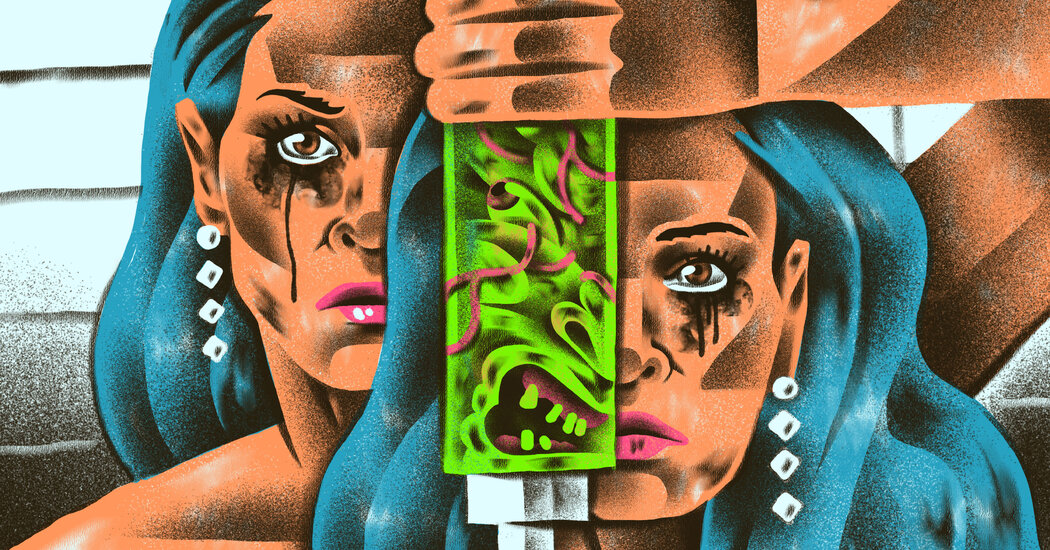

Around that time, I also wrote a poem about the kind of aesthetics I was seeing in the entertainment business, especially among women. The poem would be published years later in my first book, and in it I described women who’d gone to great lengths to stay young and desirable — the facial plastic surgeries that left them looking like “third-degree burn victims,” or the body parts that didn’t seem natural, “noses like dead poodles.” I considered myself a fiery young feminist who raged against the patriarchy.

Yet in changing my own body, I was also a hypocrite who gave in to it — because how could anyone not? Going under the knife felt like choosing a weapon I could wield in self-defense against my own disposability. It showed the world I understood the assignment of assimilation — that I could do whatever it took to fit in, never stand out, the way my ears once did.

That poem now seems like a description of a scene from “The Substance,” the body-horror film from the director Coralie Fargeat about a celebrity named Elisabeth Sparkle, played by Demi Moore. According to the gospel of Hollywood (and a TV executive pointedly named Harvey), Elisabeth, having turned 50, has reached her best-by date — and the film explores, in gory and graphic detail, the price she’s willing to pay to recapture her physical perfection and stay relevant by any means necessary.

I grew up a child actress in the sexualized spotlight of the entertainment industry. Over three decades, my responsibility not just to my craft of performing but to the performance of youthfulness was reinforced constantly — whether it was being told in my 20s by a director that the key to a long-lasting career was to stay as young as possible for as long as possible, or the time I overheard an agent describe representing actresses who are past their 30s as “hell on earth.” This kind of warped thinking has become the status quo — and women can become our own worst adversaries. Would I be less happy if I had fought against the desire to get my ears pinned back, if they still stuck out today? I don’t know — but I do think about it often, and about my willingness to align myself with the industry’s expectations.