Jacob Elordi in ‘Oh, Canada’

Cannes Film Festival

Paul Schrader’s 1999 adaptation of novelist Russell Banks’ Affliction, led by scorching performances from Nick Nolte and James Coburn, was an unsettlingly bleak meeting of two writers who share a fascination with conflicted morality and complicated relationships pushed to dark extremes. But Schrader’s return to the late author’s work, this time the 2021 novel Foregone, yields fewer rewards. For a film about big themes like mortality, memory, truth and redemption, Oh, Canada feels both slight and stubbornly page-bound, too unsatisfyingly fleshed out to give its actors meat to chew on.

Published two years before Banks’ death in early 2023, the book is an intimate portrait of a man contemplating his legacy while approaching the end of his life. It’s easy to see what drew Schrader to the story, given his own pandemic health scares and the diagnosis of his wife, the actress Mary Beth Hurt, with Alzheimer’s. But although the bones are here for a probing and highly personal character study in which a celebrated artist sets about debunking the myths surrounding his life, any deep connection between director and material is evanescent.

Oh, Canada

The Bottom Line

No, Canada.

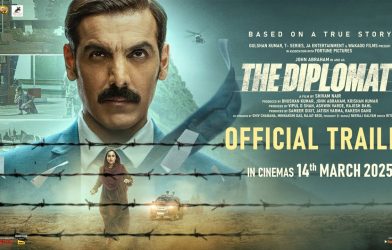

Venue: Cannes Film Festival (Competition)

Cast: Richard Gere, Uma Thurman, Jacob Elordi, Michael Imperioli, Caroline Dhavernas, Victoria Hill, Kristine Froseth

Director-screenwriter: Paul Schrader, based on the novel Foregone, by Russell Banks

1 hour 35 minutes

It’s hard to warm to the central performance by Richard Gere as Leonard Fife, a documentary filmmaker famed for his exposés of subjects including Agent Orange, sexual abuse in the clergy and illegal seal-hunting. Rising from his death bed in Montreal in the final stages of terminal cancer, Leonard agrees to be filmed in an interview conducted by the couple he sardonically describes as “Mr. & Mrs. Ken Burns of Canada.”

That would be Malcolm (Michael Imperioli) and Rene (Caroline Dhavernas), both of whom were Leonard’s students, as was his much younger wife, Emma (Uma Thurman). Increasingly irascible and fading fast, Leonard insists that Emma be present throughout, as if confessing the falsehoods and failings of his life to her is the most important part of the exercise.

The wife is not much of a role, and Thurman can’t give her anything more than a sustained note of tremulous concern, aside from the occasional moment of anger or impatience when Emma feels her husband is being pushed beyond the limits of his fragile health.

Gere is giving one of those performances often lauded for their absence of vanity, and granted, in the scenes near the end of Leonard’s life he looks like he’s walked a million miles of bad road since his peak beauty in Schrader’s American Gigolo.

With a sparse head of white bristles, a face half-covered with stubble and blotchy skin that shows the ravages of the disease eating away at the character, Leonard is clearly suffering. But Gere just plays his tetchiness; he’s a collection of tics and twitches and grimaces rather than a fully inhabited character that we’re compelled to care about.

While Leonard obviously is intended to be a complex figure with an abrasive edge, neither the man nor the supposed revelations he dredges up from the past offer much in the way of enlightenment or catharsis. It doesn’t help that he’s often stuck with banal dialogue or overripe voiceover (“She smells like desire itself.”)

As Leonard mulls over recollections that may or may not be entirely true, the film shifts somewhat randomly between color and black-and-white, and changes up aspect ratios from Malcolm’s tightly framed “Interrotron” shot to a more expansive view of the past. (Andrew Wonder was the cinematographer.) Those interludes from the late ‘60s and ‘70s are nicely enhanced by delicate indie folk songs written and performed by Matthew Houck, who records as Phosphorescent.

Leonard is played as a younger man by Jacob Elordi, who gives the movie’s most lived-in performance (never mind that he’s more than half a foot taller than Gere). But just to confuse things, young Leonard is also played by Gere without the aging makeup. They sometimes appear simultaneously, for instance when the middle-aged version peers through a window at his more youthful self, sharing some afternoon delight in bed with Amanda (Megan MacKenzie), one of a series of wives and girlfriends among whom he drifts, seemingly without ever loving any of them until Emma.

The tricks of memory are also suggested by double-casting Thurman as the depressed wife of a Vermont painter buddy, with whom Leonard has desultory sex after receiving bad news about the family he has left behind in Virginia.

How much of his past is previously known to Emma is ambiguous; often she attempts to stop the interview, insisting that her husband is inventing things that didn’t happen, that his mind can no longer distinguish between truth and fiction.

Schrader weaves together fragments of Leonard’s life non-chronologically, including an argument with his parents at 18 when he informs them he’s dropping out of college to go to Cuba. We witness a decisive moment when he and his wife Alicia (Kristine Froseth), who’s pregnant with their second child, are about to move to Vermont, where he has a teaching job. A very insistent offer from her wealthy father (Peter Hans Benson) to take over the family pharmaceutical business threatens to stymie that plan. There’s also an earlier wife, Amy (Penelope Mitchell), married in what hindsight suggests was a moment of youthful impulsiveness.

The reason Leonard remains so determined to carry on with the interview even when he’s clearly not up to it is that he sees himself as a fraud — a belief that stems largely from his status as a leftist hero, admired for his opposition to the draft. The circumstances that prompted him to flee to Canada turn out to be less straightforward, and the emotional chaos he left behind comes back to confront him 30 years later when his estranged son (Sean Mahan) shows up at a documentary screening.

All of this remains curiously inert and uninvolving in Oh, Canada, which at 95 minutes seems too hurried to layer much drama into Leonard’s purging or much pathos into Emma’s discovery of his secrets. Schrader adds a characteristically pungent stab of deceit (with shades of his 2002 feature, Auto Focus) via Malcolm’s unethical actions once Emma gets her way and halts the interview. But even that isn’t enough to imbue the story with real consequence.

What a shame that a writer-director of Schrader’s stature returns to the Cannes competition for the first time since 1988 with such a minor entry in his estimable filmography.