It is evident Hollywood holds itself in high regard. The glamour surrounding the wealthy and renowned individuals, along with the stringent gatekeeping of movie production, where only a few select titles receive the blockbuster treatment annually, exemplifies this attitude. However, beyond this facade, Hollywood harbors a disdain for competition. The decision-makers prioritize maintaining a steady flow of revenue into their personal coffers. Therefore, whenever an emerging company attempts to make movies accessible, they face significant resistance from Hollywood.

Hollywood essentially has a problem with thinking their movies should cost a lot of money, and anyone devaluing this stands in their way.

A prime example, Redbox.

When Redbox was first introduced it wreaked havoc on the industry because it was at the tail end of the Blockbuster era when rentals were basically monopolized by the giant. With Blockbuster you needed to rent a movie for several days to a week. Which overall wasn’t too bad considering movies were expensive at the time to purchase. But this was nearing the end of the era and finding a rental place was getting harder by the day. Instead overpriced digital options were available, or you could wait a few days for Netflix to send one in the mail. (Netflix didn’t start streaming until five years later)

Redbox solved two problems in one go. The machines were easily accessible, attached to the front of retail outlets and readily available on basically every corner. If one machine didn’t have the movie you wanted, another one a few blocks away could. And better yet, you could drive to any Redbox to return the movie. Redbox brought foot traffic to stores, so it was easy to work out deals with retailers to attach their boxes to outlets. When Redbox was first introduced they started with just 12 machines which grew to over 33k units that processed over 80 transactions per minute during their peak Friday nights.

Secondly it solved the issue with price. 99 cents got you a movie for 24 hours, cheaper than any other alternative and made for a great option of weekend movie nights. At the time it cost 4.99 to rent a movie digitally “on-demand” for 24 hours, and these methods typically had restrictions like only being able to watch the film once in that timeframe. Alternatively Blockbuster was charging 4.99 to 12.99 for multi-day rentals, with no 24 hour rental option. (Interesting note, Redbox’s original idea was a VHS machine called a “Video Droid,” yes named after Star Wars in 1982)

But it became a little too accessible. The cheap price of a movie meant people could see a film they liked and return the movie 24 hours later, and with it being readily accessible by any redbox on the street there was no real point in buying said movie. At the same time, DVD sales were dwindling quickly and studios now had an excuse as to why. Those damn Redbox machines!!!!

Essentially the argument was Hollywood was losing customers because people were choosing a DVD in a redbox over an overpriced digital rental, or running to the store for a copy on the shelf. The same year Redbox took off, studios were reporting a decline in sales anywhere from 13 to 25 percent, but this decline was already happening thanks to digital sales also being on the rise. In 2009 20th Century Fox, Warner Brothers and Universal then banded together and refused to sell their movies to Redbox unless they agreed to a 28 day delay (Universal demanded a 45 day delay). Redbox responded with a counter suit based on antitrust, but the two groups settled out of court and Redbox eventually accepted the delay.

In many instances studios were simply unhappy with the kiosks and told their distributors to not sell discs to them. For a while Redbox was forced to buy discs via retail, which meant they were literally buying discs off shelves to supply their machines. At the time movies cost about 25 dollars to buy, and Redbox estimated the profit off each disc was between 20-30 dollars, so there wasn’t much room for them.

On the flip side Sony Pictures and Paramount Pictures both signed deals to remain partners with Redbox. Sony was already seeing slumping sales and utilized Redbox to boost their numbers, while Paramount worked out a tricky deal that involved revenue sharing with the company. Disney, on the other hand, refused to pick sides and instead allowed their distribution partners to keep selling to Redbox with no real partnership involved. Disney CEO Bob Iger made a remark that Redbox was actually a healthy way to prevent movies from seeing bargain bins at retail stores.

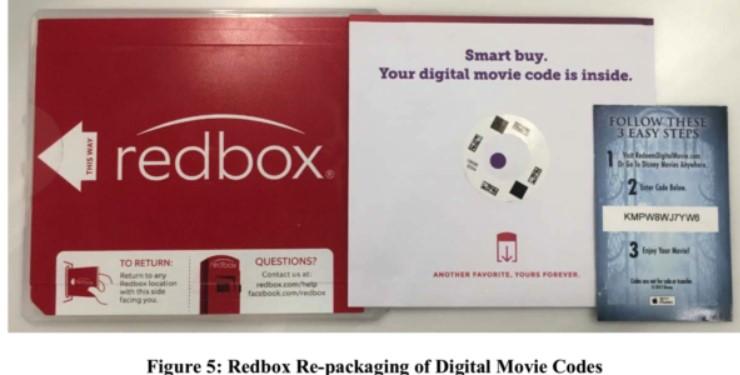

(And then six years later, Disney sued Redbox when they discovered Redbox included digital codes in the case. Redbox was organically purchasing the said codes too.)

Eventually after long fights with the studios, Redbox was able to offer several studios offerings again…but at a cost. Redbox had increased their price from 99 cents a night to 1.99, and by the end of their run it had increased to 2.25 per night. Still considerably cheaper than alternatives.

(Off topic: Netflix saw similar growth issues when their subscriber base for streaming increased from 9 million to 23 million in just 3 years. This growth led to Starz canceling their license with the streaming giant in 2012 due to the threat of losing subscribers. Additionally licensing content became considerably more costly for Netflix in the following years. Netflix once licensed over 11k titles, which has recently dwindled to just over 6k.)

But it wasn’t just Hollywood

There are gatekeepers at every entrance to Hollywood and people who have been successful in servicing the industry are also threatened when newcomers enter the fray. In Redbox’s early days these were typical mom-and-pop rental stores that were already starting to hurt. Blockbuster and these smaller outlets still held nearly 40% of the market at the time, but it was quickly dwindling with an estimate of losing upwards of 20% of that market within a few years, and with Redbox blasting their way into the market it wasn’t welcomed.

Redbox was slammed with frivolous lawsuits at every turn, but one of the more notable ones was shops claiming Redbox was renting R-rated movies to under age users. This was at a time when the digital age was taking over, so Redbox simply had an alert screen that had you confirm you were 17+ when attempting to rent an R-rated film. The shops claimed it was easy for under age users to simply agree to the screen and continue to rent the movies, something they’d easily get in trouble for.

Eventually these stores got some political leaders on their side and states like Indiana, Kansas and Texas, the city councils actually took action against them. In these towns the council pressured storefronts to either take out the R-rated films, or remove the Redbox units entirely….

Then came the downfall

A big downfall of Redbox was the reveal of their used DVD market having a bigger impact on the overall market than their rentals were. After renting a movie up to 15 times (netting the company about 30 dollars per film) they would then release the movie into the second hand market by selling it at a discount. Studios desperately didn’t like this, especially Paramount which needed Redbox to prove their kiosk would improve overall sales. In turn this made Sony and Paramount, the only two studios with distribution deals, demand the kiosk company destroy their films after the rental period ended. Redbox agreed.

But this was just the industry flexing its muscle over Redbox, meet the demands or we cut you off. This flex led the industry to realize Redbox could be easily manipulated to meet their demands. Once those initial five year deals expired, renewing them became costly both financially and via conditions that needed to be met. And like mentioned above, those demands turned into selecting what and when Redbox could sell the old discs, such as Disney forcing them to remove digital codes.

Redbox co-founder Mitch Lowe continuously fought to prove Redbox wasn’t the reason sales were dwindling with studios. In fact he had studied that retail stores with a Redbox machine only saw a 1 percent difference in sales, and the focus on new releases made films simply accessible to newer consumers who, in turn, would buy films they loved. It also opened the market to rural markets that were unable to have access to high speed internet for digital rentals.

That’s not to say Redbox didn’t try to expand into the digital market, they did (three times to be exact), and all were met by brutal competition that destroyed every attempt.

But the only real way to persuade major studios and corporations is to simply pay them. After all, Redbox was touting billions in revenue and people wanted a piece of that pie. This made Redbox start doing revenue sharing deals which ultimately were harmful to the longevity of the company. It wasn’t just the studios either, even the stores they were bringing customers to wanted more. In one instance Redbox had to create a deal with 7-Eleven that gave them a percentage of sales from units in front of stores. In 2023 Redbox stopped making these payments, and of course the machines were instantly removed.

This was just the end of a landslide of problems with Redbox locations though. The company had made countless deals with retailers (Kroger, CVS, and many others) and all were now suing for more money, and the once profitable market of DVD rentals was unable to keep up.

COVID put the final nail in the coffin for the newly acquired company. During 2021 Redbox only saw 33 new releases hit their machines, in a typical year Redbox would see more than that in a single quarter. Studios were shifting from 3rd party accessible rentals to their own streaming services. WB, Disney, Universal, Paramount, basically every studio was not meeting release schedules, and were keeping their assets to themselves. Combined with the lack of available content with the fact everyone needed to stay home, it was a disastrous mix for Redbox. This made even the most die hard DVD users start looking at streaming services because they could see films within weeks of a theater release safely in their own home.

It wasn’t just Redbox seeing the blunt end of this stick either, as Netflix and other streaming giants also saw problems with studios holding their assets hostage. Almost every studio had disbanded the idea of licensed content to favor their own streaming service.

Redbox went from nearly $1 Billion in revenue a year (2018) to just $200 million by 2023, nearly 70% decline year-over-year. Studios no longer had interest in working with them, and the lower revenue didn’t allow them to meet contracts made with retail stores. The new owner, Chicken Soup For The Soul, had no industry connections and no way to re-work the deals with the studios.

In 2020 a hedge fund had owned Redbox, previous owners being McDonalds and Coin Star. The owner decided to try and capture the “meme stock” movement and made Redbox go public, in hopes of random retail traders boosting the stock, but it didn’t work. Instead Chicken Soup For The Soul purchased the company for less than $2 per unit and absorbed the debt.

At this time the kiosk company had over 330 million dollars of debt, and the newly acquired company was blindsided by issues that went beyond the initial investment. The company struggled to simply offer Barbie at the kiosks, with most new releases skipping them entirely. Redbox went a whole year only offering a dozen new releases. Studios refused to prop the company up with favorable deals, and had no monetary interest in keeping the DVD rental business alive. It was a risky move by the company to purchase the kiosk company, but the CEO stated he “loved chaos,” and simply didn’t realize how tricky it was to navigate the Hollywood market. It went bankrupt two years later.

Now all kiosks are being removed, mostly sold for scrap, or being purchased by fans for some nostalgic gain. All Redbox official vehicles were repo’d last year.

But this is the ongoing issue with Hollywood

Every time a considerably accessible method to see new movies releases, it has been met with barriers and constant fights by the studios to get their hands on the revenue entirely. Every time an accessible outlet appears, the industry cries about “devaluing their product.” Currently new movies cost 10-20 dollars to rent digitally (sometimes more for newer releases, Deadpool vs Wolverine is currently 26 dollars to rent), and consumers becoming more aware of digital “purchases” simply being long term rentals is a growing concern.

In a competitive market, large corporations often prioritize their own profits over collaboration. While their reluctance to share their products with other companies is understandable, they overlook the importance of reaching a wider audience. As a result, gatekeepers emerge at every turn, stifling innovation and quashing new ideas.

Studios recently opted to retain their assets exclusively, a decision that nearly decimated movie theaters. However, they eventually realized the value of collaboration and began licensing their shows to third-party platforms like Netflix again. This shift in strategy, driven by declining revenue and sales, forced studios to acknowledge the importance of partnerships. While they bear the responsibility for their previous actions, the need for external outlets has prompted them to re-establish these collaborations. Running the mechanics of a rental service isn’t nearly as fun as making movies. And it won’t be long before they think they can make a quick buck yet again….

But maybe people seeing your film advertised on a big Redbox as they walk into their favorite store wasn’t entirely bad?