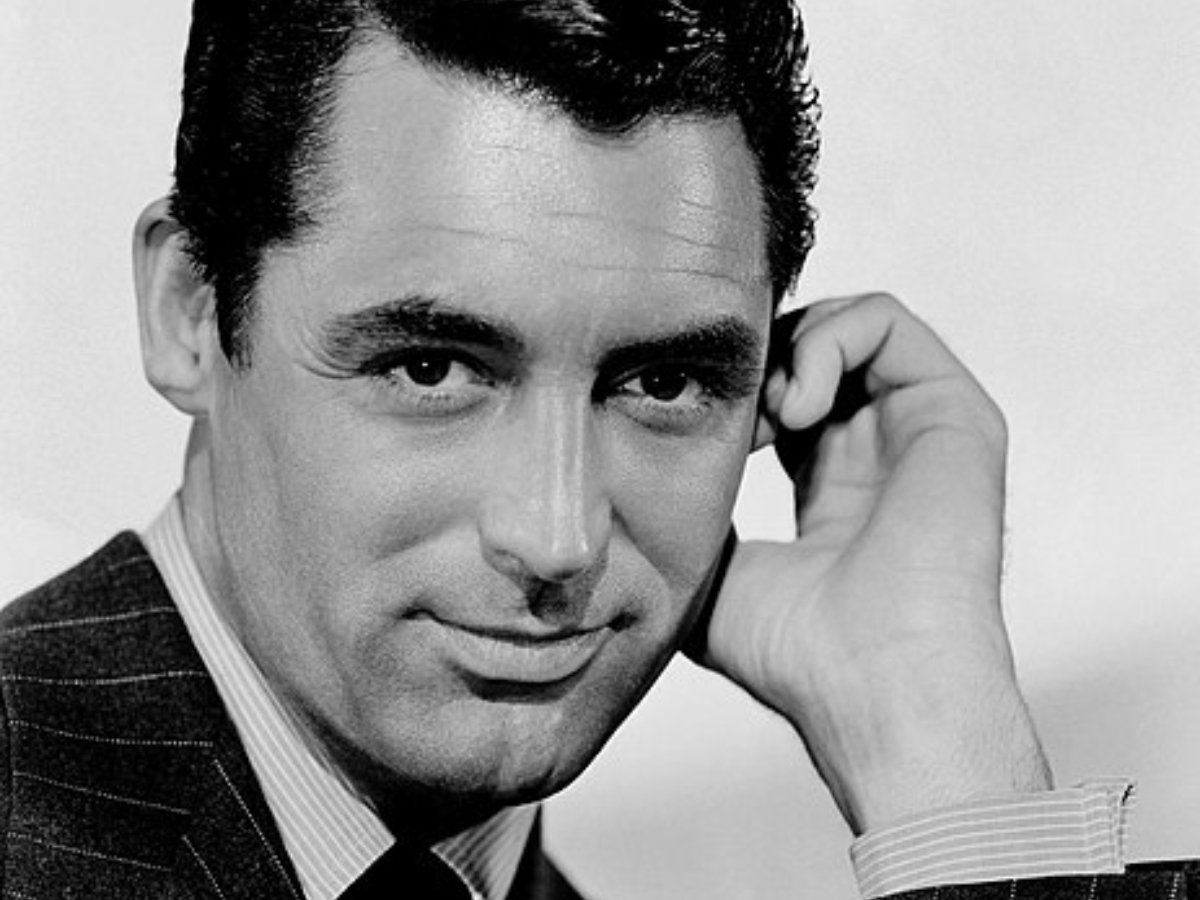

(Credit: RKO publicity)

As an actor who always projected nothing but the utmost confidence and self-belief both on-camera and off, it’s hard to believe that Cary Grant would ever find himself in the midst of an existential crisis that left him contemplating retirement.

After all, since first becoming a star in the late 1930s when he became the face of the screwball comedy through stone-cold classics like The Awful Truth, Bringing Up Baby, His Girl Friday, and The Philadelphia Story, Grant’s persona became an indelible part of Hollywood’s ‘Golden Age’.

As cliched as it is to say, for the next two decades, he was almost the ideal embodiment of the A-lister men wanted to be like and women wanted to be with. He knew it, too, which eventually became a problem. Seeking to shake up his image, he mastered that too when his collaborations with Alfred Hitchcock and Academy Award-nominated turns in Penny Serenade and None but the Lonely Heart added new strings to his performative bow.

Grant could do drama, he could do comedy, he could play the romantic lead, and he’d even shown himself capable of injecting several shades of grey into his work by playing more complex and complicated characters. And yet, he felt he went off the boil to such an extent that he was fully prepared to walk away from the business.

To put things into context, the only year between his screen debut in 1932 and 1953 that he didn’t appear in at least one picture was 1945, and Grant averaged well over one per year during that time. However, as the 1950s dawned and a new breed of actor began to emerge, he started to feel like a man out of time.

“In the early ’50s, my films were dull,” he admitted in Conversations with Classic Movie Stars. “Crisis, People Will Talk, Dream Wife: I just gave up for a while. Nobody wanted me. It was all method actors, and I didn’t look right in a torn T-shirt. They asked that wonderful actor, Basil Rathbone, why he wasn’t working anymore, and he said, ‘I blame it all on that Marlon Brando’. And that’s the way I felt, too.”

After shooting Room for One More, Monkey Business, and Dream Wife in quick succession, Grant took his longest-ever sabbatical from the silver screen. It would have been even longer if an old friend hadn’t reached out with an offer he couldn’t refuse.

“Then Hitch phones and offers me To Catch a Thief with Grace Kelly,” he said. “And things started looking up.” Re-energised by his reunion with the ‘Master of Suspense’, Grant quickly consigned his misery to the back of his mind. To Catch a Thief was his first theatrical release in 26 months, and after another 23-month stretch between Hitchcock’s thriller and 1957’s An Affair to Remember, he made up for lost time by appearing in five films in the next two years.

Related Topics