![The visual effects specialists from Weta FX for ″Kingdom of the Planet of the Apes″ pose during a press conference at CGV Yongsan in central Seoul on Tuesday. From left: Jess Seryul Sun, Erik Winquist and Charlie Seoungseok Kim [WALT DISNEY COMPANY KOREA]](https://koreajoongangdaily.joins.com/data/photo/2024/04/24/0a0d4825-abb6-450b-a008-a6320450f89a.jpg)

The visual effects specialists from Weta FX for ″Kingdom of the Planet of the Apes″ pose during a press conference at CGV Yongsan in central Seoul on Tuesday. From left: Jess Seryul Sun, Erik Winquist and Charlie Seoungseok Kim [WALT DISNEY COMPANY KOREA]

Upcoming film “Kingdom of the Planet of the Apes” is being recognized for reaching a new pinnacle in visual effects (VFX).

The live-action film, directed by Wes Bell and set to hit theaters on May 8, gives more visual nuance and detail to the emotions of its ape characters, even more than in previous installments of the reboot franchise.

VFX rendering for the upcoming film alone took up a collective 964 million hours, and if you were to process all the data from the film using one high-spec gaming computer, you would’ve had to have started from the Bronze Age, visual effects supervisor Erik Winquist, 49, said during a press conference at CGV Yongsan in central Seoul on Tuesday.

Winquist was present along with two Korean VFX experts from New Zealand-based company Weta FX: senior facial modeler Charlie Seoungseok Kim, 49, and motion capture tracker Jess Seryul Sun, 26.

Weta FX is one of the world’s most influential visual effects and animation companies, as it has worked on films in the “Lord of the Rings” and “Avatar” franchises.

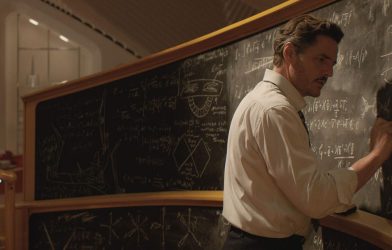

![A still from ″Kingdom of the Planet of the Apes″ [WALT DISNEY COMPANY KOREA]](https://koreajoongangdaily.joins.com/data/photo/2024/04/24/46951afa-b455-4800-b51a-5d9af9708677.jpg)

A still from ″Kingdom of the Planet of the Apes″ [WALT DISNEY COMPANY KOREA]

The ape species appear more natural and real through the help of performance capture technology, which is an upgrade from the widely used motion capture technology. While motion capture translates an actor’s movements, performance capture is capable of intricately recording an actor’s facial movements, which has been considered to be more challenging.

Despite the long and arduous process, it was necessary to take the technology up a notch because there were more lines for the apes to say in this movie.

The story jumps generations into the future after Caesar’s death in the previous film, “War for the Planet of the Apes” (2017), opening up a new chapter in the story. The protagonist, Noa (played by Owen Teague), is introduced as a young chimpanzee who teams up with Raka (Peter Macon), an orangutan, after the villainous Proximus Caesar (Kevin Durand) takes over Noa’s civilization.

![A still from ″Kingdom of the Planet of the Apes″ [WALT DISNEY COMPANY KOREA]](https://koreajoongangdaily.joins.com/data/photo/2024/04/24/e913db6b-0ec3-48d7-b60d-d51f60e696bb.jpg)

A still from ″Kingdom of the Planet of the Apes″ [WALT DISNEY COMPANY KOREA]

“In the story, 300 years have passed,” Kim said, “which means that the apes can speak better and have become more intelligent. Different civilizations now communicate and collide, which is why the technological development has helped make the characters more realistic.”

Teague had to portray a young ape that had just lost everything, so the emotion really helped his character shine, Winquist said.

While arm extenders were used to help the actors move like apes, capturing their facial expressions involved all the actors wearing helmets with not one, but two cameras attached. The cameras allowed more efficient tracking for 3-D and made the characters appear more lifelike on screen. Actors also had 101 dots marked on their faces, which tracked their expressions and muscle movement.

Most scenes were shot on location “for the richness of the frame,” Winquist said, with much of the film shot around Sydney, Australia.

Out of the film’s 145 minutes, only around 33 minutes were shot in completely digital environments because they were landscapes that didn’t exist in real life, or involved stunts that the human actors were unable to perform on location.

![A still from ″Kingdom of the Planet of the Apes″ [WALT DISNEY COMPANY KOREA]](https://koreajoongangdaily.joins.com/data/photo/2024/04/24/cc7592f0-195a-4f39-a133-cc7e48b416bc.jpg)

A still from ″Kingdom of the Planet of the Apes″ [WALT DISNEY COMPANY KOREA]

Both Kim and Sun contributed to finding the look for Raka, the chatty yet virtuous orangutan, based on the facial action coding system, or FACS. They studied research papers on how facial expressions tend to be universal for all emotions, and then they programmed the data on what facial muscles are used for which expressions.

But they did run into some problems. Orangutans have different jaw structures from humans — they are longer and their front teeth protrude out more, making every facial movement bigger than ours. Eye and brow expression adjustments were needed as well because orangutans always appear like they are smiling.

“Orangutans’ eyebrows are arched like the McDonald’s logo, and no matter how many references I’ve gone through I’ve never seen an angry-looking orangutan,” Kim said in an interview the same day after the press conference. “But we couldn’t let Raka look like he’s smiling, even in serious scenes, so there was a lot of editing done to fix that.”

![A still from ″Kingdom of the Planet of the Apes″ [WALT DISNEY COMPANY KOREA]](https://koreajoongangdaily.joins.com/data/photo/2024/04/24/0576fe72-1d3b-4512-9810-a55a49efdff4.jpg)

A still from ″Kingdom of the Planet of the Apes″ [WALT DISNEY COMPANY KOREA]

Water was another struggle for the Weta FX team to generate digitally, as it involved hairy creatures getting wet, Winquist said. The water needed to be extremely high in resolution because it would be affecting the hundreds of thousands of hairs on the apes, like when the water would drain off their fur when climbing out of the water.

A single river in the film required 1.2 billion megabytes, and “that’s not counting the rest of the water,” he said.

Though it was “daunting subject matter to deal with” for the Weta FX team, they got through it all, and now they are ready to show it off to the world.

![A still from ″Kingdom of the Planet of the Apes″ [WALT DISNEY COMPANY KOREA]](https://koreajoongangdaily.joins.com/data/photo/2024/04/24/fbeb6cc3-e30f-4b10-959a-ff45ccd7d9a9.jpg)

A still from ″Kingdom of the Planet of the Apes″ [WALT DISNEY COMPANY KOREA]

“My hope with this is that audiences don’t think about the technology and that they get swept away in the story, and they’re just watching these living, breathing characters in front of them,” Winquist continued.

The team is especially proud after noticing how technology continues to improve in its realism when it comes to both appearance and performance, and how “primitive” previous “Planet of the Apes” films appear now.

“At the time, we thought that was the pinnacle,” Winquist said.

BY SHIN MIN-HEE [shin.minhee@joongang.co.kr]