illustration by Ben Turner

illustration by Ben TurnerI. James

A man and a woman sway to a Frank Sinatra song in their dimly-lit living room. The man has an old, pronounced scar running from ear to mouth. He wears a white tank top stained with drops of fresh blood. He cradles the woman in his arms, and they drift gently to the music. Their son, meanwhile, lies in the bed of an older girl, desperate to be held, desperate for a warmth—physical or otherwise—that can erase the cold memory of the canal that runs just behind their apartment building. There’s a song playing in the background:

I know I stand in line until you think you have the time to spend an evening with me,

And if we go someplace to dance, I know that there’s a chance you won’t be leaving with me.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

The thing about humans is that they produce garbage. Sanitary napkins, mottled banana peels, rinds of cheeses and oranges—one waxy, the other citrusy. These all end up in a black garbage bag to be taken away, ideally, at least once a week somewhere far, far away. In 1975, however, garbage lined the streets and backcourts of Glasgow, Scotland for thirteen weeks when the sanitation workers went on strike to protest mass layoffs.

Lynne Ramsay’s debut feature Ratcatcher (1999) opens on the early days of this strike: there are some swollen black bags lining the front yards and curbs of the street where 12-year-old James Gillespie (William Eadie) and his family live, but they have not yet overtaken the green grass or the cracked gray sidewalk. The garbage is a reminder of decay, a suggestion that if we neglect our filth, it will fester and rot, becoming home to colonies of insects and families of rats.

Garbage is made: it’s the result of some kind of action, material and organic. Can the result of inaction rot in a similar way? Ramsay saddles her young protagonist with this question, one that observes the clash between the dual definitions of innocence—naivety and guiltlessness.

James lives with his parents and sisters in a poor housing complex that has no indoor toilets or running hot water. His family is on a list to be re-housed in a newer complex, but as they wait, the decrepit streets and courts of the old estate are his home, and he frequents the grimy canal that runs behind the apartments with other boys in the neighborhood.

On one such day, he’s playing rough with his friend Ryan, who goes under. James does nothing. Or, more specifically, he does nothing to help: he immediately runs home and watches from his living room window as his friend’s lifeless body is pulled out from the water. In the following days, he continues to observe silently as his surroundings transform into the prototypes of grief: a weeping mother, a helpless father, a black hearse, pitying neighbors. It’s archetypal because it’s informatory: though he doesn’t directly engage with the death by verbalizing his feelings, he’s very much engaging with the situation in an observational way, ravenous for information. This interest has two faces: the first is academic, gauging what it means for a death to have occurred; the second is self-serving, trying to understand what role his inaction played and whether the guilt he feels is warranted and proportional.

The camerawork expressly hints at this kind of negotiation. As the black hearse carrying Ryan’s body leaves their street, James sits on a brick wall and watches. There’s a juxtaposition to the way cinematographer Alwin H. Kuchler captures him: James is centered squarely in the foreground of the frame, but he’s out of focus; the focus is instead on the background, where the black hearse is slowly driving by. Only when the car exits the frame does James’s shape sharpen. We’re stationed behind him but we nonetheless understand: James is starting to realize the severity of his situation.

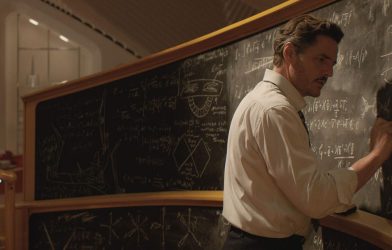

This feeling he carries is antithetical to everything he sees around him. He’s surrounded by the embodiments of consequences, from the garbage bags that are beginning to grow in number in his city to the pronounced white scar that bisects his father’s (Tommy Flanagan) cheek, a reminder of one of the most potent actions: violence.

Ramsay is interested in the imperfect complexity of this kind of education, suggesting that a conscious understanding of an action or its consequences does not inherently result in a changed approach. You see, James witnesses another drowning—or, at least, what looks like one.

In an apartment on a nearby street—this one with indoor plumbing—James sits on the toilet lid while Margaret Anne (Leanne Mullen), the teenage girl he has recently befriended, lies in a tub of water, her hair dotted with the suds of head lice soap. She fully submerges and the camera focuses on James, who sits frozen in place as a tear rolls down his cheek. Interspersed with this scene is one featuring James’s father running into the canal to save a neighborhood boy from drowning. Da is in his underwear and leaps into the water despite not knowing how to swim, a stark contrast to James, who watches for seventy seconds without moving an inch as Margaret Anne is underwater. She emerges, gasping for air, proudly noting how long she had held her breath.

The genius of Ramsay’s debut is that she doesn’t care to explicitly denote the lines that run between innocence and guilt, awareness and responsibility—instead, she’s more interested in examining how the blur between the two inevitably separate factions. Her work is subjective, carrying with it a fallible sense of certainty, an exercise akin to determining the correct hue of paint with the naked eye.

In fact, this is exactly what James’s parents attempt to do early in the film. Da brings home a sealed can from work, proud to have secured good quality paint in a nice color. It’s pale blue, he tells Ma (Mandy Matthews), it’s “pastel,” it’ll brighten up the rooms. He pries the tin lid of the can open and shows Ma the paint, to which she chuckles and tells him the color is gray. Da carries the can closer to the window to get a better light and contentedly confirms that it’s blue. We never get to see the color of the paint in the sunlight; the camera instead focuses solely on the faces of Ma and Da, the former skeptical, the latter proud.

They have a complicated relationship: Ma carries the burden of being a source of warmth and light for her children while they grow up in difficult circumstances, both familial and societal, while Da shoulders a dual burden, that of breadwinning compounded with his alcoholism. Still, despite the volatility of their relationship, they’re united in their ambition: a better living space—cleaner, newer, and with an indoor toilet.

This leads to perhaps the most iconic moments of Ratcatcher: a triad of scenes, all occurring in the same housing development project.

The first occurs in the first act. James takes a bus to the end of its line, ending up in an almost-built estate, where the houses are unfinished: the windows don’t have any glass panes, the appliances are either missing or covered in plastic, and the doors have yet to have locks installed. He explores the interior of a house, empty and clean, a sharp departure from his own living situation. As he enters the kitchen, he sees a beautiful view out the window: a field of golden wheat, swaying gently beneath a blue sky. There’s no asphalt, no garbage bags, no man-made canal. It’s like a painting, almost too beautiful to comprehend. James leaps through the window and the camera follows him, traveling through the empty frame and into the field, where he frolics and somersaults.

In the final act, James returns to this estate for the second time. This time, the houses are finished, though still uninhabited. The locks have been installed, and so have the glass panes in the windows. We watch from inside the same kitchen as James peers through the window from the outside before turning around and walking into the field, its hue now more yellow than gold. We don’t follow James into the field: there is a glass window, after all, stopping us.

The final scene of the film starts in the field instead of in the house. We see James and his family carrying furniture through the wheat, on their way to the estate. But the tone of this scene is not entirely uplifting: it’s edited in parallel to one of James jumping into the canal and floating submerged in its murky waters. Is one a dream and the other reality? Are they both fantasies—or both real?

Ramsay leaves us to sit in this uncertainty, though not without staying consistent to her filmic language: while the first two scenes were filmed from the kitchen, the camera capturing this final vignette never enters the house.

II. Morvern

A woman wearing only a pair of pink underwear takes a sip of wine and looks at herself in the bathroom mirror. Her vision must be tinted bronze because she is wearing aviator sunglasses. She walks over to the bathtub where her dead boyfriend lies: he killed himself a couple of days or weeks before, it’s hard to tell. A pink Panasonic MP3 stuck to her torso with scotch tape plays a song that goes like this:

You held up a stagecoach in the rain, and I’m doing the same,

Saw you hanging from a tree and I made believe it was me,

I’m sticking with you ‘cause I’m made out of glue,

Anything that you might do, I’m gonna do too.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

When Morvern Callar (Samantha Morton) finds her boyfriend dead on the floor of their shared apartment, body lying prostrate on the floor, she lies down beside him. She opens the Christmas presents. She reads the suicide note he left her on the computer. She goes to work at the grocery store. She parties with her friend. She does everything but move his body. His bloody body lies in the doorway between the kitchen and the living room as if it sprung up there as naturally as moss.

As with Ratcatcher, the viewer of Ramsay’s second feature film Morvern Callar (2002) is immediately confronted with inaction. Morvern goes about her regular routine for a couple of days before she decides to do something with the corpse, and even then, her decisions are unexpected: she disposes of her boyfriend’s body, takes the money he relegated for the funeral, jets off to Spain, and publishes the novel manuscript he left on his computer under her own name.

And yet, despite the fact that she’s shown to be far more decisive than the timid James, she shares with him a voracious hunger for comprehension, a desperate desire to understand her situation. It’s not a fatalistic inclination: she’s not concerned with reflecting on her morality to see whether she deserved the tragedy that befell her. Instead, she yearns to feel that she’s not alone in her feelings.

Morvern’s desire for understanding can be summed up neatly in a scene that, like in Ratcatcher, features paint and a window. While waiting to meet a literary agent, Morvern paints her nails with great care and holds them outstretched in front of a window, moving her fingers gently and surveying the color. But it’s a bright, sunny day outside, so Morvern is wrapped in shadow—we don’t see what she sees; we don’t see the color of her nails.

In the final scene of the film, Morvern goes to a nightclub and dances along with the other sweaty, gyrating bodies. While they’re dancing to Europop, she’s listening to a song on the MP3 player her boyfriend left her. To an outsider, she looks no different than everybody else, but true unity can only come from the individual.

III. Eva

A little boy, emulating Robin Hood with his white tunic and green bycocket, wields a blue plastic bow. He shoots an arrow, whose arrowhead is replaced with a yellow suction cup, at the kitchen window where his mother washes dishes. He draws the bow again, this time aimed at the target of the practice range his father lovingly set up for him in their suburban backyard. He lets loose, but we don’t see if he has hit his target: we linger on his face, which is bereft of joy or frustration. A moment later, we see adolescent arms draw an arrow on a professional bow. The boy has grown. A finger tab has replaced his bycocket. His arrows no longer have suction cups at their ends. A song plays only for us to hear:

I never can forget the day when my dear mother did sweetly say,

You are leavin’, my darling boy, you always have been your mother’s joy.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

We Need to Talk About Kevin (2011), Ramsay’s third feature length film, opens on the same image as Ratcatcher: white curtains fluttering in front of a bright window, set to human noise. But while Ratcatcher’s opening is more mundane, showing Ryan wrapping himself up in the fabric with everyday noise in the background, the curtains in Ramsay’s newer feature are scored by the sounds of chaos: we hear screaming and the sharp staccato sound of sprinklers going off, before a sudden cut brings us to La Tomatina, a tomato-throwing festival that occurs annually in Spain. Eva (Tilda Swinton) is drenched in red tomato juice, crammed between bodies who are similarly stained, and at first glance, it looks like a bloody massacre. But no, it’s tomatoes. There’s no violence.

There are many such moments in We Need to Talk About Kevin where Ramsay plays with dyadism, demonstrating how easy it is to breach the borders of categories we believed to be safely secure. In one instance, the screen fills with bright red lights that flash in the same way that police sirens do, before sharpening into focus and revealing themselves to be the red numbers on an alarm clock. In another, while walking in the street with her husband, we hear Eva scream with glee, but the high-pitched shriek melds with that of a police siren. All things stem from or turn into an emergency; alarm; the color red.

The film is an adaptation of Lionel Shriver’s disturbing book of the same name. The non-linear story follows Eva prior to and following a school massacre perpetrated by her son Kevin (Ezra Miller). There’s a near-cosmic sense to the red and the sirens, as Ramsay makes us feel Eva’s alarm and uncertainty towards the antisocial behavior of her son in the everyday and the mundane.

Despite the signs, Eva doesn’t intervene in her son’s disturbing behavior. Sure, she tries. When he’s an infant and refusing to speak, she brings him to the doctor. When he’s a toddler and purposefully ruining her things, she raises this issue with her husband. But each time, she allows herself to be dissuaded, to be convinced that each troubled phase will pass. And so when we first meet her, interviewing for a job amidst a community that blames her for her son’s actions, she welcomes their blame, carrying the guilt on her face, in her posture, and in her subdued manner of speech.

She’s a woman who lives in the past, trying to piece together what went wrong in Kevin’s upbringing and who, if anyone, is to blame. But Ramsay elevates this story to be more than just an exploration of nature versus nurture: Ramsay tasks Eva with reflecting on the silences, the things she didn’t do and say, the moments she held back. Like James and Morvern, Eva is driven to understand.

This culminates in the final scene of the film. “I want you to tell me why,” she says to Kevin. They sit at a metal table in a prison visiting room, Kevin’s new buzzcut hinting at his imminent transfer to an adult penitentiary. The phrasing is significant. It’s a statement, not a question—nor is it a command. Eva is vocalizing the internal battle she has been waging since Kevin’s birth—the why could be probing for an answer to their complicated relationship as much as for the reasoning for the massacre.

Kevin’s response is honest, but it lacks the absolution that would deliver Eva relief through its certitude. “I used to think I knew. Now I’m not so sure.”

IV. Joe

A man dressed in a sharp blue suit with an American flag pin on his lapel is bleeding out on a kitchen floor. Another man, this one disheveled and frustrated, though considerably less bloody, sits beside him and asks him questions about how his mother was murdered. The dying man reassures him that she was shot in her sleep. This appears to be a relief to the disheveled man, and he lies down on the floor too. There’s a song playing in another room, and it drifts into the kitchen. The two lie on the floor and sing along together with mumbling, incoherent voices, one from grief, the other from a looming death:

But I, I took the sweet life, I never knew I’d be bitter from the sweet,

I spent my life exploring the subtle whoring that costs too much to be free,

Hey lady, I’ve been to paradise, but I’ve never been to me…

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

In a way, the central character of Ramsay’s fourth film, You Were Never Really Here, deviates from his predecessors James, Movern, and Eva. Joe (Joaquin Phoenix) is not vying for an understanding; we meet him at a point in his life where he understands too well. He understands the nature of violence, the consequences of inaction, and, most importantly, the ignorance of the rest of the world in knowing or wanting to know these lessons.

Joe is haunted by the violence he witnessed in his past—domestic abuse in his childhood, the deaths he encountered while working for the FBI—so he reverts to a self-soothing technique he adopted in childhood: suffocating himself with a plastic bag. He’s a hired gun who specializes in rescuing trafficked girls, and his experience with violence has led him to enmesh himself in a deeply violent underworld.

He is tasked with rescuing the young daughter of a local politician, who was taken into a trafficking ring—with, we later find out, her own father’s permission. Joe locates Nina (Ekaterina Samsonov) at a governor’s home in a sluggish state, dissociated from the things done to her. He sees himself in her—as they are both victims of violent childhoods—but this reflection shatters when he discovers that she had taken action to kill her own abuser, her razor beating Joe’s hammer to the kill. It’s a contrast to the feverish yet brief flashbacks we are shown of Joe hiding away in his closet, head in a plastic bag, while his father abuses his mother.

Killing the governor on behalf of Nina would have been catharsis for Joe, retroactive relief and absolution for moments in his past when he acted as bystander, witness, discoverer. Despite the aggressor being taken out, Joe still carries his burden with him.

He takes Nina away from the house and to a cheery diner, where, while Nina runs to the washroom, he shoots himself in the head with a gun. His blood splatters everywhere – a bald man behind him is speckled red but continues on with his conversation – and a waitress brings by a receipt, placing it casually on the table, which is pooling with blood.

This is a fantasy. It’s all in Joe’s head. But it reflects how he views the world: blind to violence. Nina returns and wakes him from his macabre reverie: “It’s a beautiful day,” she says simply, a prompt to get on their way and to ward off his thoughts of despair. They leave the diner and the film ends.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

There’s an ineffable comfort in realizing that a work of art—a song, a film, a book, a poem—perfectly coincides with where you are in your life. It suggests a certain pendulous coherency: you’re constantly in motion, and so is art—being reimagined, repurposed, reassessed, and redefined—and in that one glorious moment, whether by accident or by design, you meet at a point where there is clarity. Your respective iterations are compatible in every way: your emotions inspire a heightened resonance in the harmony, the prose captures the words you were searching for—it’s a synergy that feels rare to find.

Lynne Ramsay scatters songs throughout all four of her feature-length films that directly chronicle the actions or feelings or predicaments that her characters are experiencing. The lyrics are pseudo-narration, recounting the romantic troubles, psychotic tendencies, parental anxieties, and conspiratorial plots that her respective films focus on. This literalness is consistent throughout Ramsay’s oeuvre, and could feel heavy-handed were it not treated with such care.

What feels like divine interception and interpretation is a conditional relationship, one that can only be wholly symbiotic if its context and complexities are not investigated.

Twenty-five years ago, James leapt through a window to an idyllic field that represented all of his desires: purity and freedom. Ratcatcher marks the beginning of the fascination one of our greatest working directors has with inaction as a force that propels us to understand ourselves and the world around us.