Born 100 years ago next month, the maverick star of A Streetcar Named Desire, On the Waterfront and Apocalypse Now was to acting what Elvis was to music

And, OK, so he let himself go a bit in later years, and sabotaged his own career by appearing for money in dodgy pictures, but few would argue with the notion that he may well have been the greatest screen actor of all time.

He was certainly the most influential. On the set of The Godfather, Al Pacino, James Caan, John Cazale and Robert Duvall sat mesmerised at his feet while he told them tales of golden-age Hollywood. They and all the male screen method actors of the last 50 years or so, Robert De Niro included, will have been inspired by Brando’s example in some way.

But he was not a straightforward hero, seldom easy to love. And it is hard to imagine him thriving in today’s post MeToo world. Married three times, the father of at least 11 children, he was associated during his life with a staggering array of women whom, to put it mildly, he did not always treat chivalrously.

And then there were the men. Truman Capote, an unreliable witness, claimed that Brando had sexual relationships with many men, but did not consider himself homosexual. In his memoir, David Niven seemed to confirm this idea. And Marlon himself once said of his close friend Wally Cox that, “if Wally had been a woman, I would have married him and we would have lived happily ever after”.

A complex man, then, but a fabulous actor. He was born 100 years ago, on April 3.

Brando’s contempt for rules knew no bounds, and can be traced to his unfortunate childhood. He was born in Omaha, Nebraska, and didn’t have the best of starts. His parents were alcoholics and he despised his controlling and sarcastic father. He came to hate male authority figures, and deeply distrusted women: after getting himself expelled from several midwestern high schools and a military academy (insubordination was a recurring theme), he ran away to New York in 1943 to study acting.

Though only 18, it was something he already knew a lot about. When he was small, and his mother Dorothy was blind drunk, he would playact and assume roles to get her attention. He got to be good at it, and when he began studying under the great method coach Stella Adler, she immediately noticed his precocious talent.

It was she who taught him the Russian ‘emotional memory’ technique, by which painful experiences honestly summoned could enrich a performance: Brando had lots of those at his disposal. After getting kicked out of several summer shows, he was cast in a 1944 Broadway production of the play I Remember Mama, which was a hit.

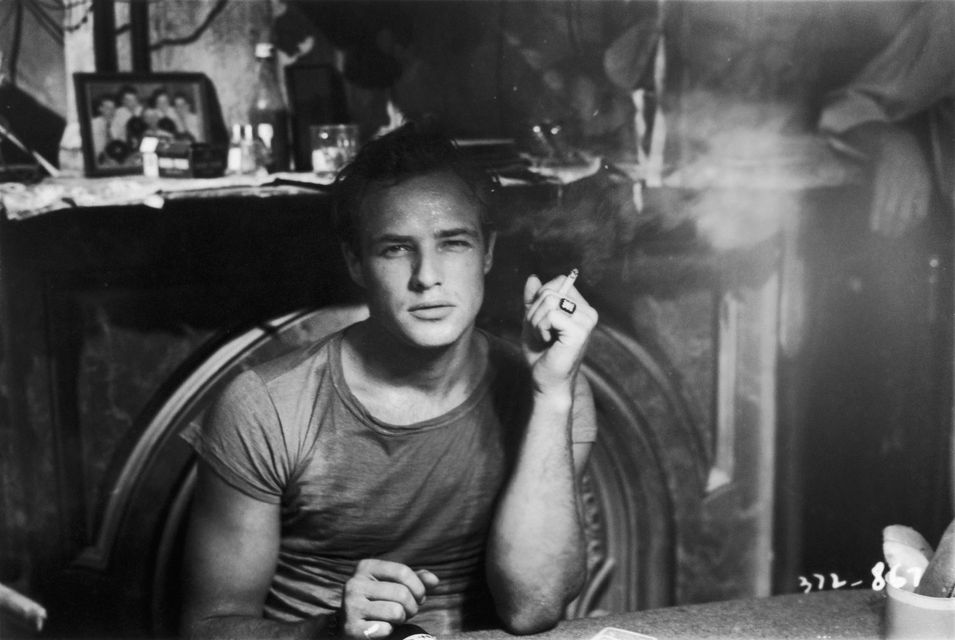

Screen breakthrough: Marlon Brando in A Streetcar Named Desire

But his big break came in 1947, when he was considered for a major role in Tennessee Williams’ new play A Streetcar Named Desire. The production’s director, Elia Kazan, wanted Brando to play Stanley Kowalski, a working-class brute, because he believed the young actor was capable of transforming him into something more than just a sweaty villain.

Williams was not convinced, so Brando drove to Cape Cod to visit him. Legend has it that when he got there, the electricity and plumbing were out, so the actor fixed them both before giving what Williams later described as “by far the best reading I have ever heard”.

A Streetcar Named Desire’s legendary Broadway production ran for two years and made Brando someone to watch. He made his screen debut playing a traumatised war veteran in Fred Zinnemann’s 1950 drama The Men, having prepared for the role by spending a month in bed in a military hospital so he could convincingly play a paraplegic veteran. And in 1951 he brought Kowalski to the big screen in Kazan’s film version of Streetcar. His performance was explosive yet without apparent artifice, and seemed different from anything previously seen on an American screen.

According to Dustin Hoffman, Brando would often chat to cameramen and other actors even after the director called action: only once he felt he could deliver his lines as naturally as he could would he start. In the 2015 documentary Listen to Me Marlon, a collage of audio tapes Brando had made during his life, he explained that, before he arrived, Hollywood actors had been like breakfast cereals — that is, entirely predictable.

That he certainly was not. In 1953, he hit the pop cultural mainstream playing the mumbling, moody leader of a motorcycle gang in The Wild One. It was hardly a classic, but Brando was electrifying: when someone asked his character what he was rebelling against, Marlon sneered and said: “What have you got?” He might have been talking about himself.

Oscar triumph arrived in 1955 with On the Waterfront, and his extraordinary portrayal of Terry Molloy, a punch-drunk ex-boxer and dock worker who refuses to kowtow to a New York mob boss. The film contained that famous “coulda been a contender” speech, and was the source of many a Brando impersonation.

But just as he hit the top, Brando already seemed to be disenchanted with stardom, and even with acting. In his autobiography, he said that when he first saw On the Waterfront in its entirety, he was “so depressed by my performance I got up and left the screening room — I thought it was a huge failure”.

And perhaps that explains why Brando, who could have had his pick of roles through the late 1950s and 60s, chose daft comedies and even musicals over more serious parts. Sayonara, Guys and Dolls, The Teahouse of the August Moon might have been a bit of a laugh, but hardly played to the actor’s strengths, and seemed to imply that he cared more about money than the work.

In the 1960s, he tried directing, with mixed results, and starred in so many bad films that his career began to slide. He was a diva, directors said, impossible to work with.

Second Oscar: Marlon Brando in The Godfather

That’s certainly what Paramount executives told Francis Ford Coppola when he had the temerity to suggest Brando for a key role in his forthcoming mob saga, The Godfather. They wanted someone reliable, like Laurence Olivier, to play mob boss Vito Corleone (imagine that!), and Paramount boss Stanley Joffe went so far as to tell Coppola that “Marlon Brando will not be in this picture, and you will not be allowed to discuss it”.

Which sounds over the top, but you could see his point: by this stage, Brando had become more or less uninsurable, and was prone to imposing bizarre conditions, changing or ignoring scripts, leaving sets.

Undeterred, Coppola went to visit him and asked him to film an audition. Brando, still youthful and handsome, put boot polish in his hair and stuffed cotton wool in his cheeks to create in the instant a character that would win him his second Oscar. He chose not to attend the 1973 Oscars in protest at the treatment of Native Americans, and sent as his emissary, one ‘Sacheen Littlefeather’, who turned out not to be Native American at all.

Coppola, a glutton for punishment, would hire Brando again, to play a key role in the 1979 war epic Apocalypse Now — Colonel Kurtz, a decorated US army officer who has gone feral in the Vietnamese jungles. Marlon’s antics on that film would become the stuff of legend.

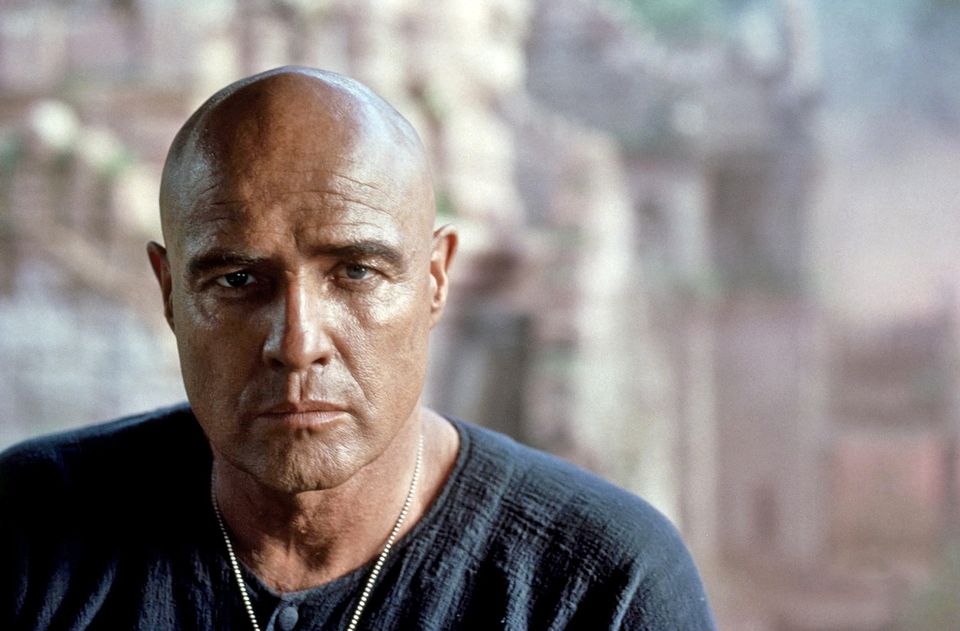

Reclusive madman: Marlon Brando as Colonel Kurtz in Apocalypse Now

In signing up for the role, Brando agreed to certain conditions. He would “get trim, and stay in shape”, arrive on set on time, co-operate with his director and read in advance Heart of Darkness, the slim novella by Joseph Conrad on which Coppola’s story was based. On foot of these not unreasonable conditions, he would be paid a million dollars for one week’s work.

When Brando showed up in Thailand he was overweight and hadn’t so much as glanced at the first page of Conrad’s story, never mind the script. Because of his weight, he had to be photographed in half-light. He didn’t know his lines, and instead improvised a strange speech about “the horror”. Then he shaved his head without Coppola’s approval because he felt it added to the character’s drama.

A disaster then — except that, somehow or other, Brando’s performance worked. Apocalypse Now had been a long and tense build-up to army assassin Martin Sheen’s meeting with this reclusive madman, and if anyone else but Brando had played Kurtz, the audience would have felt let down.

Brando the man remained something of an enigma. Passionately committed to political causes such as civil rights and the plight of the Native Americans, he was considered a royal pain in the ass by many in the movie business. Yet most of the actors who worked with him found him helpful, inspiring and funny.

In a slick hatchet job in The New Yorker, Truman Capote portrayed him as a stupid ape. “The little bastard had a perfect memory,” Marlon said bitterly afterwards, “he remembered every f***ing word I said.” But Capote was prone to jealousy, and Brando, an avid reader, was anything but dim. In fact, he enjoyed baiting pinheaded studio executives with supposedly helpful suggestions: on Superman, for instance, he suggested that his character should appear on screen as a giant green bagel.

Perhaps his contempt for Hollywood was a bit too corrosive, and maybe he did squander years when he could have been putting his remarkable screen presence to better use. But just look at what he left behind.

He was to film acting what Elvis Presley was to popular music: there was before him, and after him. Marlon Brando changed everything.