The 10 Greatest New Hollywood Movies, Ranked

The New Hollywood era of the late 1960s through the 1970s was a revolution. A new wave of directors, young, rebellious, and unafraid of risk, shattered the old studio formulas, trading neat, feel-good stories for grit, realism, and aesthetic experimentation. Influenced by European art film but rooted in American anxieties, these filmmakers redefined what movies could be, creating a legitimate golden age. It was a time when films were taken seriously by the general public, and the result was a string of masterpieces.

From melancholic, reflective works like The Last Picture Show to generation-defining psychological dramas like Taxi Driver, these movies defined New Hollywood but also transcended it, becoming pillars for modern cinema. They are now widely regarded as classics, timeless statements about a certain time when artistic possibilities were endless, and filmmaking felt new, dangerous, boundless, and full of promise. These are the best movies of New Hollywood, ranked based on their overall quality, their place within the movement, and their legacy as profound works of art.

10

‘The Last Picture Show’ (1971)

“Nothing’s ever the way it’s supposed to be at all.” The Last Picture Show is one of the definitive portraits of small-town America. Shot in luminous black and white, the movie depicts a Texas town in decline. There, young people struggle with the emptiness of their lives, and the older generation clings to faded dreams. The cast is studded with rising stars, including Jeff Bridges, Cybill Shepherd, and Timothy Bottoms, all radiating a restless energy.

The movie manages to be epic and intimate at the same time, nostalgic as well as unsparing. The closing of the town’s cinema serves as both a literal and metaphorical marker of change; the end of innocence, of tradition, and of collective identity. It’s a sign of an era coming to a close. In many ways, The Last Picture Show summed up what New Hollywood did best: telling stories Hollywood had never dared to tell before.

9

‘Bonnie and Clyde’ (1967)

“We rob banks.” In many ways, Arthur Penn‘s Bonnie and Clyde was the spark that lit the New Hollywood flame. Bold, violent, and stylistically daring, it shocked audiences with its unapologetic depiction of outlaw lovers as folk heroes. Warren Beatty and Faye Dunaway play their parts with a volatile mix of glamour, recklessness, and tragic inevitability. Penn’s masterstroke was merging the French New Wave style — replete with jump cuts, shifting tones, and ironic detachment — with distinctly American subject matter.

For instance, the climactic ambush, with its balletic slow motion and unflinching violence, genuinely stunned 1967 audiences. It marked a turning point for what violence could look like on screen. The film challenged censors, divided critics, and captured a countercultural mood of rebellion. Looking back, it’s almost impossible to imagine New Hollywood without it: Bonnie and Clyde made it clear that cinema was changing forever, and that the outlaws were now behind the camera as much as on screen.

8

‘The Deer Hunter’ (1978)

“This is this. This isn’t something else. This is this.” The Deer Hunter is one of the most ambitious films to come out of New Hollywood, a sprawling exploration of war, trauma, and community. Beginning in a small Pennsylvania steel town, it follows a group of friends (including Robert De Niro, Christopher Walken, and John Savage) whose lives are shattered by the Vietnam War. Director Michael Cimino takes his time, contrasting the exuberance of the early wedding scenes with the devastation that follows, creating a before-and-after portrait of American innocence destroyed.

The result is a film that’s sweeping in scope yet devastatingly personal. It’s also loaded with iconic moments, the most infamous of which is the Russian roulette sequence, symbolizing the randomness of survival and the psychological toll of war. The Deer Hunter‘s Best Picture win cemented it as one of the last great masterpieces of its era. Indeed, Cimino’s subsequent failure with Heaven’s Gate was widely seen as New Hollywood’s death knell.

7

‘Mean Streets’ (1973)

“You don’t make up for your sins in church. You do it in the streets.” Although not Scorsese‘s first movie, Mean Streets was his first crime classic, announcing the arrival of a major new voice in American cinema. A gritty, semi-autobiographical look at small-time mobsters in New York’s Little Italy, it vividly captures the restlessness and contradictions of men torn between loyalty, violence, and Catholic guilt. Harvey Keitel stars as Charlie, a man trying to reconcile his criminal life with his religious conscience, while Robert De Niro, in a star-making turn, plays Johnny Boy, a reckless, self-destructive wildcard.

Scorsese’s camera is as alive as the performances; restless, roaming, capturing the raw energy of its characters and their environment. The use of handheld cinematography, along with pop music, gave the film an immediacy that felt utterly new. The aesthetic contrasts made the sudden bursts of violence hit even harder. All in all, Mean Streets showed crime as both seductive and soul-crushing.

6

‘Network’ (1976)

“I’m as mad as hell, and I’m not gonna take this anymore!” Network is often called prophetic, but that almost undersells it. This scathing satire of television anticipated the rise of reality TV, news-as-entertainment, and the commodification of outrage; in many ways, we’re all living in it now. At the center of it all, Peter Finch gives an electrifying, Oscar-winning performance as Howard Beale, a news anchor who suffers a breakdown on air and becomes the “mad prophet of the airwaves.” His iconic cry became one of cinema’s most quoted lines.

Alongside him, Faye Dunaway and William Holden add complexity as executives torn between ambition, ethics, and survival in a cutthroat industry. Sidney Lumet directs it all with a veteran’s sharpness, letting Paddy Chayefsky’s brilliant script drive the tension. The result is both a satire and a thriller, a film that skewers corporate media while thrilling audiences with its ferocity. Few films from the ’70s feel as urgent and relevant today.

5

‘One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest’ (1975)

“But I tried, didn’t I? Goddammit, at least I did that.” One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest is a cornerstone of New Hollywood, not just because it’s rebellious and anti-authoritarian, but because it’s profoundly human. Based on Ken Kesey‘s novel, it follows Randle McMurphy (Jack Nicholson in one of his greatest performances), a convict who fakes insanity to serve his sentence in a psychiatric hospital. There, he collides with the oppressive Nurse Ratched (Louise Fletcher), sparking a monumental battle of wills. These two characters become stand-ins for the clash between individual freedom and institutional control.

The supporting cast, including Danny DeVito, Christopher Lloyd, Will Sampson, and Brad Dourif, adds to the authenticity, each character vivid and unforgettable. On the directing side, Miloš Forman balances humor with tragedy, making McMurphy’s defiance both inspiring and heartbreaking. In the end, the movie perfectly encapsulates the spirit of the ’70s: distrust of authority, celebration of misfits, and the cost of rebellion.

4

‘Apocalypse Now’ (1979)

“I love the smell of napalm in the morning.” Apocalypse Now is both the pinnacle of New Hollywood ambition and a cautionary tale of its excess. A hallucinatory Vietnam War epic inspired by Heart of Darkness, the film follows Captain Willard (Martin Sheen) as he journeys upriver to find and kill the rogue Colonel Kurtz (Marlon Brando). Though the movie is obviously brilliant, its production was infamously chaotic, plagued by weather disasters, illness, and budget overruns. It’s impressive that Francis Ford Coppola was even able to pull it off at all.

Apocalypse Now shifts from combat spectacle to surreal nightmare, capturing the madness of war in unforgettable images, like helicopters attacking to the sound of Wagner, napalm lighting up the jungle, and Kurtz’s shadowed monologues. All these elements make it the ultimate statement of New Hollywood’s ambition: cinema as madness, spectacle, and truth all at once. However, like The Deer Hunter, it also hinted at the movement’s coming collapse, and the end of the era of auteurs armed with gargantuan budgets.

3

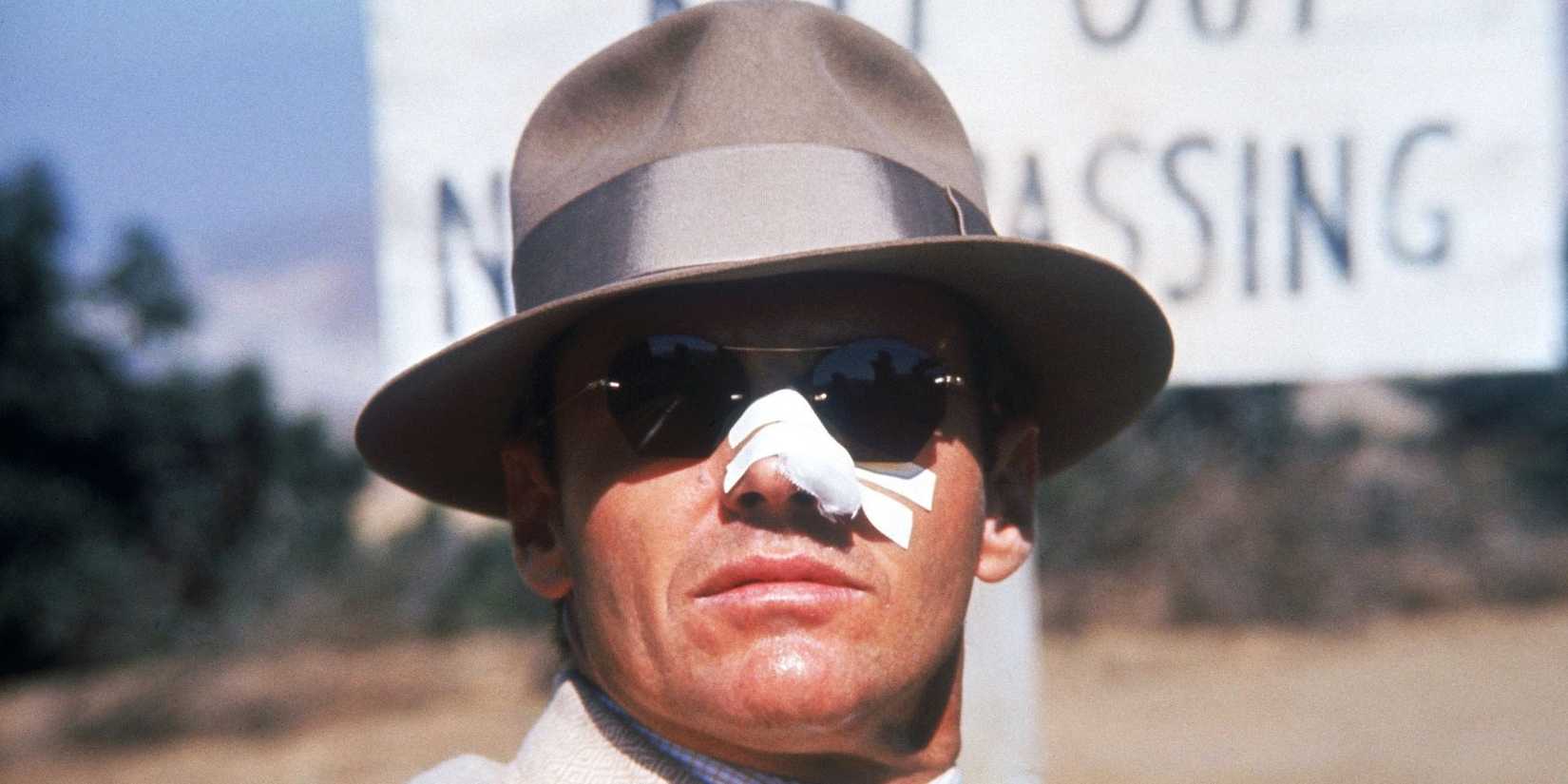

‘Chinatown’ (1974)

“Forget it, Jake. It’s Chinatown.” Chinatown channeled the cynicism of the ’70s into one of the greatest neo-noirs ever made. A top-of-his-game Jack Nicholson leads the cast as Jake Gittes, a private investigator who stumbles into a conspiracy involving water rights, incest, and political power. Faye Dunaway gives one of her finest performances as the tragic Evelyn Mulwray, while John Huston exudes menace as her powerful father.

Robert Towne‘s screenplay is often hailed as one of the best ever written. The structure is clever and inventive, though it never loses sight of the characters, developing each of them in ways that feel authentic. In the process, Chinatown twists familiar noir tropes into something darker and more devastating. The bleak ending, in particular, vividly captures the hopelessness of a system too rotten to fight. It all adds up to a thriller, a drama, and a scathing allegory for corruption, all wrapped in elegant direction. Stylish, subversive, and unflinchingly grim.

2

‘Taxi Driver’ (1976)

“You talkin’ to me?” Scorsese’s defining project from this era is Taxi Driver, a searing character study of alienation and rage. The film is both a psychological thriller and a social critique, a statement on moral decay. Robert De Niro delivers one of the greatest performances in film history as Travis Bickle, a lonely cab driver who spirals into violence and delusion. Paul Schrader‘s screenplay captures Travis’s descent with unnerving precision, while Scorsese’s direction drenches the city in grit, neon, and menace.

While the climactic shootout and the famous “You talkin’ to me?” scene have become indelible cinematic moments, the movie’s true power lies in its unsettling ambiguity: is Travis a savior, a monster, or both? For this reason, Taxi Driver is one of the most disturbing and brilliant films of the era, a New Hollywood landmark that still provokes debate today. All these decades later, it still feels fresh and vital.

1

‘The Godfather’ (1972)

“I’m gonna make him an offer he can’t refuse.” The Godfather is a veritable cultural institution. Coppola significantly elevated Mario Puzo‘s novel, taking a straightforward mobster tale and turning it into a modern myth, as well as a grim vision of the American Dream. It helped that he had once-in-a-lifetime performers at his disposal. Marlon Brando‘s Don Vito is iconic, but it’s Al Pacino‘s Michael who anchors the film, transforming from reluctant outsider to ruthless crime boss in one of cinema’s most chilling (yet fully believable) arcs. Each delivers a towering performance.

Coppola handles their stories with a deft touch and an eye for memorable images, including the opening wedding, the infamous horse’s head, the restaurant assassination, and the climactic baptism intercut with murders. Nino Rota‘s score enhances everything with an operatic grandeur. Winner of Best Picture and universally acclaimed, The Godfather remains the definitive New Hollywood masterpiece, the film that proved American cinema could rival Shakespeare in scope and tragedy. We’re unlikely to see anything quite like it ever again.