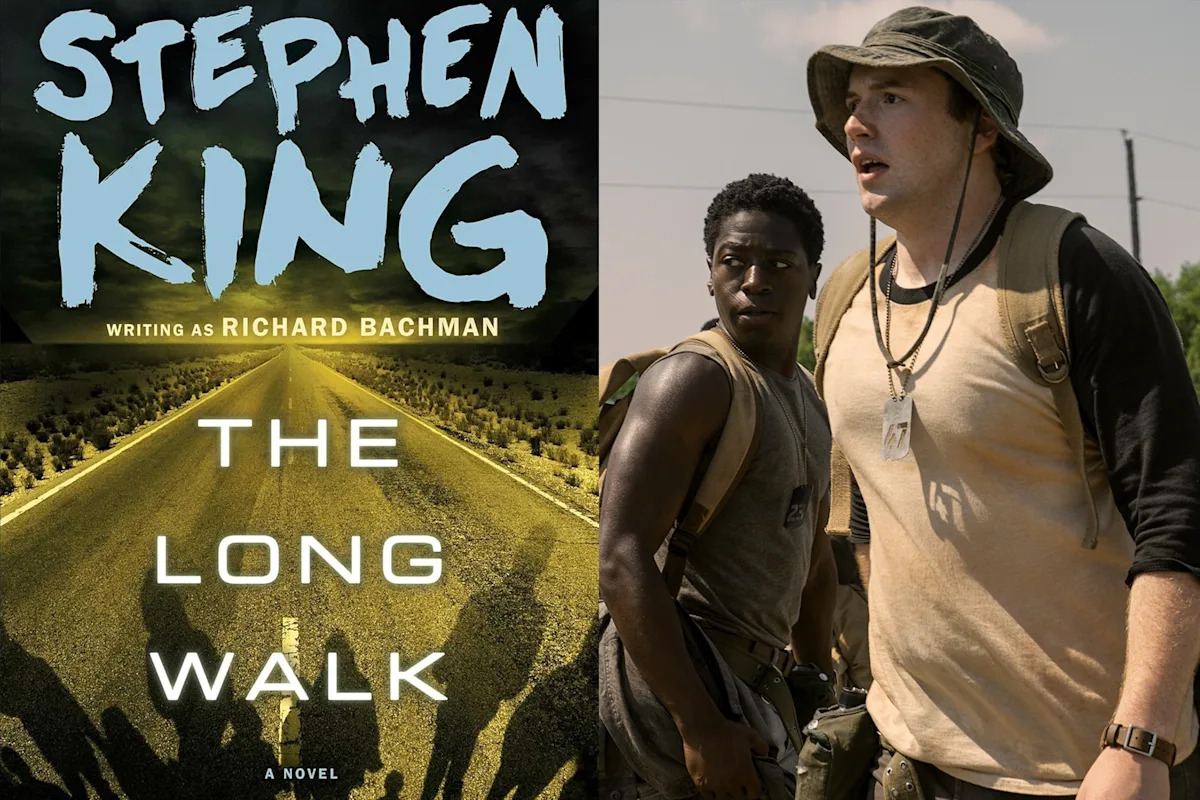

How Does The Long Walk Movie Differ from Stephen King’s Original Novel?

In retrospect, it seems like director Francis Lawrence’s four Hunger Games movies (soon to be five) were merely a dystopian warm-up for The Long Walk. Now available to stream on digital platforms, the film is, perhaps, the best and most affecting Stephen King adaptation since Frank Darabont gave us the one-two punch of The Shawshank Redemption and The Green Mile.

The book-to-screen translation of King’s sixth published novel—written under the Richard Bachman pseudonym—is a harrowing depiction of brotherhood and the loss of innocence we all experience on the proverbial long walk called life. Compared to King’s other works (like IT, for instance), The Long Walk is a more straightforward and less narratively complex tale, preferring a single point-of-view and no major subplots.

For just over 300 pages, the reader occupies the mind of Ray Garraty, one of 100 participants in the Long Walk, an annual event held by the military police state that was once a democratic America. Starting at the northernmost tip of Maine, on the U.S. border with Canada, the punishing competition overseen by an imposing authoritarian figure known only as The Major has just one rule: walk. Maintain a certain speed or you’re given three warnings. When those run out, you’re shot on sight—no questions asked.

Last man standing receives untold riches and their heart’s deepest desire.

For More on Stephen King:

Horror Master Stephen King’s Best Film Cameo To Date Is Actually in This 2012 Romantic Dramedy

This John Carpenter Movie About a Killer Car Is Still One of the Wildest Stephen King Adaptations

The Mist: Ranking the Monsters of Frank Darabont’s Creature-Filled Stephen King Adaptation

How different is The Long Walk movie from Stephen King’s original novel?

The Long Walk is extremely faithful to its 1978 source material, even going so far as to take place against the backdrop of a dystopian shadow of the late ’70s. In addition to paying homage to the year in which King first released the book, the setting also imbues the film with a paradoxical timelessness that wouldn’t have been present if the story simply unfolded in modern day.

One must also commend Lionsgate for allowing the project to be R-rated, so as not to neuter the shocking, yet necessary, moments of violence as walkers are picked off along the route.

The screenplay written by JT Mollner (Strange Darling) keeps a lot of the book intact, with entire swaths of dialogue and character interactions lifted directly off the page. Like its inspiration, the film’s emotional center revolves around the close fraternal relationship between Ray Garraty (Licorice Pizza‘s Cooper Hoffman) and Peter McVries (Alien: Romulus‘s David Jonsson).

While adaptation changes are often reviled by literary purists, The Long Walk movie contains five major deviations from the novel that not only actually make sense, but enhance King’s ideas.

5 major differences between The Long Walk book and movie

For one, the film whittles down the number of walkers from 100 to a much neater 50 (one from each state).

Secondly, we get some helpful background on why the Long Walk exists, whereas the book keeps it rather vague. According to the movie version of The Major (Mark Hamill), the yearly trek was instituted following a second civil war that tore the United States apart and plunged it into a state of financial instability. The Long Walk helps represent the importance of work ethic and never fails to inspire a greater spike in production. “We have the means to return to our former glory,” proclaims The Major. In other words, the competition is meant to make America great again.

The third big change is a rule that prohibits spectators along the route until the very end, when the group has been culled down to two walkers. In the book, the road is almost always packed to the teeth with eager onlookers who show up to cheer on the participants, witness some carnage, or get their hands on a souvenir—be it a discarded shoe or a piece of hastily produced fecal matter (yes, really).

Keeping the sidelines clear for the adaptation makes sense both financially and narratively. There was no need to hire a ton of extras or pay for VFX crowd extensions in post-production. At the same time, the eerie lack of other people effectively drives home the crushing isolation and hopelessness the walkers face as their casual hike turns into a waking nightmare.

Mark Hamill The Long Walk

Fourthly, the movie provides Garraty with an actual motivation for taking part in what amounts to a suicidal undertaking against the wishes of his distraught mother, Ginnie (Judy Greer). While the character in the novel can’t quite work out what compelled him to sign up, his onscreen counterpart has a clear goal in mind: revenge. He’s going to win and use his wish to kill The Major as payback for the execution of his dissident father years before (the book version of Garraty Sr. is merely taken away by the dreaded Squads and never seen again).

Lastly, we have the ending, which is completely different from King’s source material where Ray Garraty wins the competition, but seemingly loses his mind in the process. As The Major tries to congratulate him on a job well done, Garraty continues to walk, and even finds the strength to run, in pursuit of some dark figure—maybe Death?—only he can see.

The movie, on the other hand, completely flips the script by having Ray sacrifice himself so Peter McVries can win. It’s a heartbreaking, yet inevitable, subversion of what viewers expect after nearly two hours of Garraty being set up as the emotionally developed frontrunner. Surely he won’t die and leave his mother all alone, right?

Another mainstream studio release would most likely blink and give the audience that semi-happy ending, but The Long Walk ain’t that kind of picture. Instead, the victorious Peter uses his one wish to ask for a carbine and shoots The Major dead, fulfilling Ray’s ambition before walking off into the rain and, hopefully, a better future.